This Essential Agency Helps the Region Contend with a ‘New Normal’

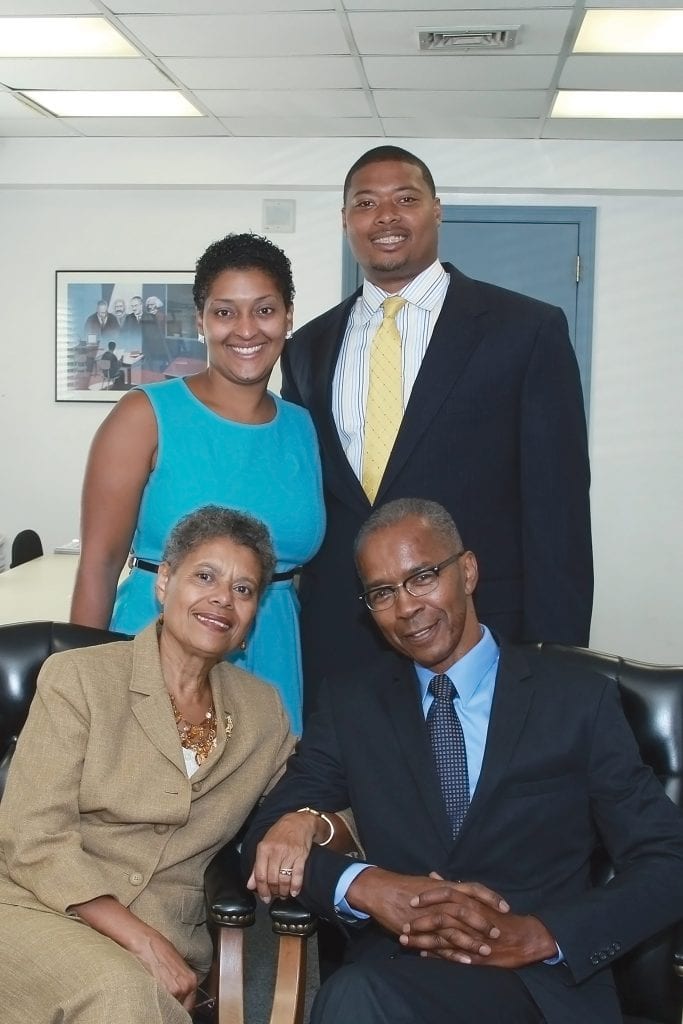

Andrew Morehouse, executive director of the Food Bank of Western Massachusetts

As Andrew Morehouse talks about the Food Bank of Western Massachusetts, its history, mission, and future, he makes early and frequent use of numbers.

And for a good reason — actually, several of them.

They bring this story into focus better than any words probably could, said Morehouse, executive director of the Hatfield-based nonprofit since 2005. The numbers punctuate the tremendous amount of need in this region, and … well, they usually wind up surprising people and then inspiring them.

Here are just a few:

Over the past calendar year, the Food Bank has served more than 225,000 people seeking what is known as ‘food assistance.’ That’s not necessarily 225,000 different people, Morehouse acknowledged; that number is at least 100,000 and probably closer to 200,000 — significant no matter what the actual total is, because the population of this region is only about 900,000. Nearly one-third of those served (30%) are children, 14% are seniors, and the rest are adults ages 19-64.

“Do the math. People working at minimum wage or near minimum wage working full-time can’t meet all their basic expenses, including food, so something has to give. And often, it is food.”

As for meals distributed, that number is more than 9.6 million for the four Western Mass. counties, and more than 5 million for Hampden County alone. Those meals add up to 11.6 million pounds of food, or the equivalent of 145 tractor-trailers packed from one end to the other.

And here are perhaps the most surprising, disturbing, and inspiring numbers. The total amount of food distributed in 2005 was 5.6 million pounds, just over half what it is today. Meanwhile, the number of people served spiked after the Great Recession to more than 200,000, and in the decade since, it hasn’t gone down, even though the economy has recovered significantly by every statistical measure.

The Food Bank of Western Massachusetts relies on a small army of volunteers to carry out its broad mission.

“That’s certainly alarming,” said Morehouse, adding that all these numbers add up to three simple yet also quite complex words: ‘a new normal.’

“There’s been an economic restructuring, as often happens after recessions, which has brought about a dramatic change in the workforce,” he explained. “Many people, if they are working, are in lower-paying jobs. And that results in a lot of families not being able to support themselves, even if people are working full-time.

“Do the math,” he went on. “People working at minimum wage or near minimum wage working full-time can’t meet all their basic expenses, including food, so something has to give. And often, it is food.”

Confronting this new normal in a proactive manner could be considered the unofficial mission of the Food Bank, which was created in 1982 and first housed in a tobacco barn in Hadley.

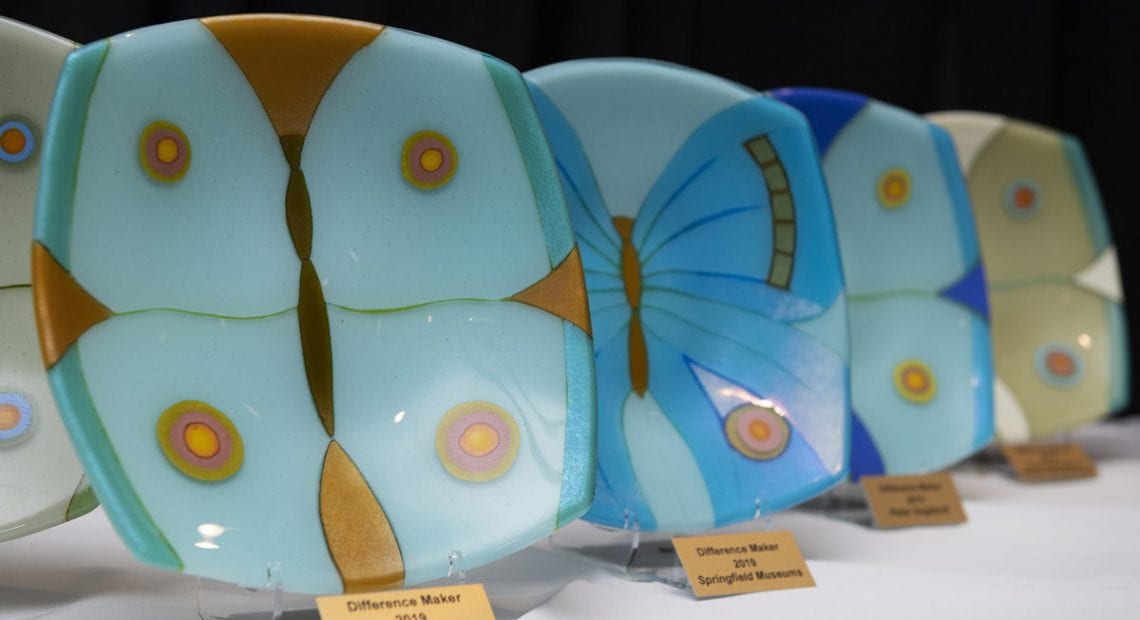

And this mission is carried on in a number of ways, said Morehouse, noting that collecting and then distributing food for more than 9 million meals is obviously the most visible and impactful manifestation of the agency’s work and the quickest, most profound explanation for why this agency is being honored as a Difference Maker.

“People are not going to wear a sign around their neck saying, ‘I’m hungry.’ There is a lot of stigma and shame attached to not being able to meet your basic needs, especially food. So there’s a real challenge there in terms of public education.”

Indeed, Monte Belmonte, program director and morning show host at WHMP radio and architect of Monte’s March, an annual trek during which he pushes a shopping cart to raise money for the Food Bank, called the agency ‘mother ship hunger’ that provides food to a number of area food pantries and soup kitchens, and essentially enables them to carry out their work.

“When I go into these emergency food providers across our region, all of them say they couldn’t do their work; that’s how essential the Food Bank is to fighting hunger here,” he said. “If it weren’t for this huge piece of the puzzle, all those other dominoes would be in huge trouble.”

But the Food Bank is also attacking the root causes of this large and persistent problem through an ambitious initiative called the Coalition to End Hunger.

Launched in 2017, the coalition is a collaborative network of leaders and organizations focusing on providing integrated services for those who need them, erasing the stigma associated with hunger and advocating for public policy solutions.

As just one example, he noted the agency’s work to bring awareness to — and a possible solution for — the so-called ‘cliff effect.’ Not a recent phenomenon but certainly a growing problem, this cliff effect refers to a situation where people who want to work, and are often being given help to join the workforce, often don’t because the income they would earn would make them ineligible or less eligible for benefits such as food assistance.

Andrew Morehouse says the Food Bank is coping with what a ‘new normal’ when it comes to the number of area residents needing help and the volume of food it distributes.

Looking toward the future, the Food Bank is blueprinting ambitious expansion plans, said Morehouse, adding that, given the ‘new normal’ this region is facing, the agency will need to nearly double the size of its 30,000-square-foot Hatfield headquarters to effectively carry out its broad mission.

Plans are preliminary, he went on, adding that a capital campaign will certainly be needed for this expansion to become reality. When asked for a price tag, he said he didn’t know what that number might be at this time.

What he does know is that all those other numbers cited earlier are expected to increase in the months and years to come. The food bank will go on being a Difference Maker in this region, he said, but the challenge will only continue to grow in scope.

Crunching the Numbers

Morehouse told BusinessWest that hunger is what he called “an invisible problem.”

By that, he meant that, in many ways, it’s not easy for many people to see or fully comprehend the scope of the problem in this area, especially in times like these, when the economy is, in most ways, doing well and unemployment rates are approaching record-low levels. And also because of the persistent stigma attached to hunger.

“People are not going to wear a sign around their neck saying, ‘I’m hungry,’” he said. “There is a lot of stigma and shame attached to not being able to meet your basic needs, especially food. So there’s a real challenge there in terms of public education.”

Meanwhile, beyond being invisible in nature, hunger, or the need for food assistance, is an often misunderstood problem.

Indeed, the common perception is that many of those seeking such assistance are capable of working and are not, opting instead for a handout. There are certainly a few that might fit into that category, said Morehouse, but the vast majority of people receiving assistance would rather not be. However, circumstances dictate that they must, so they do, although pride does keep some away who are truly in need.

“We need to debunk that myth that people go hungry because of their fault,” he explained, adding that battling this stigma, as well as the many misperceptions about those seeking food assistance, has been part of the Food Bank’s mission since it was created more than 35 years ago by area church leaders. It is now one of 200 food banks across the country under the umbrella of a national organization called Feeding America.

As noted, it started in a tobacco barn in Hadley (a location chosen because the intent was for the agency to also serve Southern Vermont, although it did that for only a short time), but within a year, land was purchased in Hatfield for a headquarters facility that includes a large warehouse and administrative offices.

As he offered a tour of that warehouse, Morehouse noted that the food distributed by the agency comes from a number of sources and agencies with like-sounding acronyms. These include the state government (MEFAP), the federal government (TEFAP), local farms, the agency’s own farm, retail and wholesale food businesses (including CNS Wholesale Grocers, which built a huge warehouse literally next door in Hatfield), community organizations, and individual donations.

“With state funding and food donations from local farmers, we receive more than 1 million pounds of fresh vegetables every year,” he explained, while pointing to cases and large storage bins of food that arrived from a host of various sources, and correcting another misperception about food banks. “Contrary to the stereotype that food banks distribute unhealthy food, a third of the food that we distribute is fresh vegetables; we get vegetables from supermarkets, and we actually buy vegetables from Canada over the winter months because they know how to store the harvest up there.”

Once received and processed, the food is distributed to a number of member agencies or through the Food Bank’s own direct-to-client programs such as its Mobile Food Bank or its Brown Bag: Food for Elders program. These member agencies, located across the four counties of Western Mass., include pantries, meal sites, shelters, rehabilitation facilities, senior centers, and more.

And this is where some confusion exists, said Morehouse, noting that many believe the Food Bank is one of these pantries, such as Rachel’s Table, Kate’s Kitchen in Holyoke, or the Amherst Survival Center.

“Our strategic plan is to continue to increase the amount of food we distribute every year, until or unless we see things get better. But here we are in a period of dramatic economic growth, and there are still 225,000 people receiving food — and we know that another recession will come.”

Instead, it is, as Belmonte described, the mother ship for those smaller distribution facilities, a ship that needs fuel — in the form of donations of food, money, time, and energy; indeed, the Food Bank relies on a small army of volunteers to keep its multi-faceted operation running smoothly.

Meanwhile, donations from the public, attained through a host of fundraisers, including Monte’s March, are used to support the infrastructure that enables the Food Bank to carry out its mission, said Morehouse.

“Those donations support the capacity we have, between staff and trucks and warehousing, to be able to receive the food that’s either donated or paid for by the public sector,” he explained. “That’s the magic that enables us to turn $1 that is donated into the equivalent of three meals.”

But while food distribution is at the heart of the agency’s mission, there is much more to the work known as food assistance, said Morehouse, adding that the Food Bank is engaged in helping area residents on a number of fronts, including SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) outreach and enrollment, nutrition outreach, and the broad realm of advocacy.

Educating the public about the problem of hunger and its vast dimensions is a big part of the mission, said Morehouse, adding that many of the families being served by the agency have incomes that exceed the thresholds established for SNAP benefits, but are not high enough to adequately feed that family. He offered an example.

“For a family of four, that threshold is about $44,000,” he said, in reference to the ceiling for SNAP benefits. “So if you’re making $45,000 a year, you can’t make ends meet, yet you’re not eligible for SNAP benefits. So if you can’t feed yourself, you can go to a local food pantry or meal site and get some food to get through the week or the month until the next paycheck comes. To get by, a family of four would need to earn about $56,000; so there’s a gap of $12,000.”

Word-of-Mouth Referrals

That gap, and, more specifically, the steady, alarmingly high number of people facing such a gap, explains not only the need for the Food Bank but why the long-term strategic plan calls for an expansion of the Hatfield facility, said Morehouse.

Elaborating, he said that, when the Food Bank goes about calculating how much food it will need to distribute, either to area member agencies or through its own programs, it takes that number cited earlier — 225,000 people — and multiples it by the number of times each individual might visit. This takes us to that other number — 11.6 million pounds of food — which, he said, is almost certain to increase in the years to come.

“Every year that I’ve been at the Food Bank, we’ve increased the amount of food we’ve distributed,” he explained. “In 2005, we were distributing 5.6 million pounds of food; last year, it was over twice that amount.

“Our strategic plan is to continue to increase the amount of food we distribute every year, until or unless we see things get better,” he went on. “But here we are in a period of dramatic economic growth, and there are still 225,000 people receiving food — and we know that another recession will come.”

This reality, and the need to be able to respond to it, is one of the forces that started Belmonte on his march back at the start of this decade. The program has its roots in a food drive staged by the radio station, he explained, but was inspired by the knowledge that the Food Bank, with its enormous buying power, can do more with dollars than it can with donated cans of soup.

So Belmonte started marching from Northampton to Greenfield with a shopping cart souped up (pun intended) by students at Smith Vocational and Agricultural High School, broadcasting and raising money as he went.

In its first year, the march raised $13,000 for the Food Bank. The latest installment, staged last November, raised $294,000. The numbers are just one manifestation of how the event has grown in size — and meaning.

Indeed, the march now covers two days and much more ground; the trek is now from Springfield to Greenfield. And Belmonte, who likened himself to Forrest Gump in the scenes where that movie character is running across the country, has picked up a lot of company in his march.

“There were hundreds of people joining us at various points along the 43-mile route, including all the newly elected legislators in Western Mass. and U.S. Congressman Jim McGovern, who has done this march at least six times now,” said Belmonte, adding that this strength in numbers has helped bring more than money to the Food Bank — it’s helped raise awareness of its all-important mission.

And still more awareness comes with some stops those marching make to a few of the member agencies served by the Food Bank.

“Some of these people who are marching along with us have never been to a food pantry and seen how one works,” he said. “So it brings the pieces to the puzzle together in a rather interesting way for people.”

Thus, the march has become part of Belmonte’s work as a member of the Coalition to End Hunger, an important extension, if you will, of the Food Bank’s mission. The coalition is focusing on three primary areas of work:

• A policy team that identifies and supports changes that will help resolve the underlying causes of hunger;

• A service-integration team that develops a network that will help those who are food-insecure through initiatives ranging from integrating nutrition programs into other safety-net programs to increasing access to healthy food in food deserts and food swamps; and

• A communication and education team (Belmonte’s a member) that addresses the lack of understanding and education about food insecurity, and the stigma attached to the problem, through a targeted media campaign.

“We’ve invested in a public media-education campaign to drive traffic to a website called coalitiontoendhunger.org,” Morehouse explained, “where we’re telling real stories of real people that will help shatter the myth that people are hungry because they’re lazy or they don’t want to work or because they have a drug problem.

“One would do better to not assume or judge, but to understand this problem and come up with smart ways to address it,” he went on, adding that this is the essence of the coalition and its work.

Belmonte agreed, and said his efforts to assist the food bank have certainly evolved over the years and expanded beyond the physical pushing of a shopping cart and asking for donations, and into the realm of education.

“I’ve learned so much about food insecurity and the myths surrounding it, and I wanted to do much more than a publicity stunt,” he said of his work with the coalition. “Using the tools of marketing to help destigmatize this issue is really important to me.”

Food for Thought

As he put the Food Bank and its broad spectrum of work in perspective, Morehouse recalled (he said it was something he’d never forget) a tour of the Charlemont area he was given by a woman who runs a food pantry there.

“She drove me around the rural roads of Charlemont to show me where people lived and tell the stories of the people who lived in those houses and also frequented the pantries,” he told BusinessWest. “It was eye-opening to see the condition of those houses, but it’s just one example of how there’s lots of people in rural communities, and urban communities, who are just scraping by — really struggling.

“People who don’t experience that and don’t live in those circumstances, just don’t have a clue of how much people are struggling to survive,” he went on, adding that it is part of the Food Bank’s mission to not only give people a clue but create enough momentum to confront that new normal he described, in the manner in which it needs to be confronted.

And that’s why, beyond those 9.6 million meals and 11.6 million pounds of food distributed, this agency is a true Difference Maker.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]

It was almost a decade ago now when Bill Ward, then the executive director of the Regional Employment Board of Hampden County, stepped to the podium at the Log Cabin Banquet & Meeting House in Holyoke to accept the first Difference Maker award presented by BusinessWest.

It was almost a decade ago now when Bill Ward, then the executive director of the Regional Employment Board of Hampden County, stepped to the podium at the Log Cabin Banquet & Meeting House in Holyoke to accept the first Difference Maker award presented by BusinessWest.

Frederick Hurst clearly recalls where he was the April afternoon in 1968 when Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed. It was a job interview — a job he decided not to take.

Frederick Hurst clearly recalls where he was the April afternoon in 1968 when Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed. It was a job interview — a job he decided not to take.