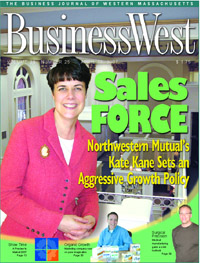

SALES FORCE

Northwestern Mutual’s Kate Kane Sets an Aggressive Growth Policy

For years, the Northwestern Mutual Financial Network has marketed itself as the “Quiet Company.” It is still that, at least when compared to other giants in this industry, says Kate Kane, who nonetheless plans to make some noise as the new managing director of the company’s Springfield office. She has some ambitious plans for growing that facility and its market share — and possesses a background in talent recruitment and development she believes will help her achieve them.

Kathleen Kane was just looking for something to do between her graduation from Vassar and the projected start of her quest for a doctorate at the University of Chicago, the next step down a path toward a long-planned career teaching English.

That was the thought process as she took a job in 1986 in the Worcester County office of what is now known as the Northwestern Mutual Financial Network. But it only took a few months with the firm for her to adjust her thinking and her career plans and become, in her words, a ‘Northwestern lifer.’

“Ultimately, I decided I would rather be making money than spending more money to become a college professor, which I was no longer sure I wanted to do,” she explained, adding that both her parents were college professors, and early on, she had little doubt she would become an academic. There have been no regrets about not taking that road, she said, describing the academic scene, or the tenure track, as it’s called, as “almost a feudalistic system,” in which time served, and not necessarily performance, are the basis for advancement and reward.

That’s a far cry from the system she now administers as managing director of Northwestern Mutual’s Springfield office, which recently merged with the Hartford facility (more on that later). Here, performance is what matters, and driving agents to reach their top potential (teaching, in plain and simple terms) has been something Kane has been doing for most of her life with the company.

Indeed, after working as an office administrator in Worcester, she was lured to Northwestern’s Springfield office by the man she would eventually succeed, then-Managing Director Paul Steffan, to be his recruiter. The official title would become ‘director of recruitment and training,’ and, later, ‘field director.’

That role involved recruiting, developing, mentoring, coaching, and joint sales work with new agents. She served in it for three years, becoming quite proficient and rather comfortable.

But Steffan, recently promoted to regional vice president for the Midwest Region and now working in Northwestern’s home office in Milwaukee, always had a thing about people becoming too settled.

“He would always say, ‘now that you’re comfortable, let’s see if we can make you uncomfortable and move on to something else,’” Kane recalled. “He would say that someone was either green and growing or ripe and rotting, and he wanted people to keep growing.”

So, at Steffan’s urging, Kane became managing director of the company’s Worcester office, now part of the Boston facility, and quietly grew that branch. But deep down, she desired a return to Springfield, where she had built what she called a “connection,” and seized upon the opportunity to lead the office housed at 1351 Main St. last fall when Steffan moved on and up.

Looking forward — she said she doesn’t waste any time looking back — Kane has ambitious plans to grow the office, in terms of volume and agents. “There’s a lot of room in here,” she said glancing around the former bank headquarters facility now housing the Springfield office. “I can add 10 agents a year for a decade and still not fill the place.”

Securing top talent to fill available office space is obviously Kane’s biggest challenge, but one she approaches with abundant energy and years of experience in both recruiting and training. She approaches her assignment with the philosophy that she’s not looking for people who can merely sell, but individuals who are entrepreneurs in the purest sense of the word.

“And entrepreneurship is hard,” she said, adding that it takes a certain type of individual to succeed in this field. “It takes a special person to bang on doors and talk about things that people just don’t want to talk about.”

Policy Statement

There are a great many things that fall into that category, she continued, starting with life insurance, the product this company and others like it is most associated with, but also such things as long-term care insurance, retirement planning, and other products and realms that are now part of the broad package now offered by Northwestern.

And by Kane’s estimate, probably nine out of 10 individuals — across all income levels — can use help of some kind.

“It’s a common misperception that successful people have their finances all sewn up,” she said. “They don’t … I see it every day. I have many clients who are outwardly very successful. They have a nice house, lots of nice stuff in the house, a very nice income. But when you dig in and look at what they’ve got, where it is, and how it’s doing, nine times out of 10 there’s plenty of room for improvement.

“I have some clients making $500,000 or $700,000 a year and they haven’t paid attention to what they need to pay attention to,” she continued. “They’re living the life, but they’re not thinking about what life in the future is going to look like.”

Helping people realize they need some kind of help, and then effectively providing it, are, in very simplified terms, the keys to success in this industry, said Kane, who was quickly attracted to the business and the life, as she called it, and thus abandoned those plans to teach English Lit.

Instead, she merely went into a different kind of teaching.

Specifically, it was within a company-wide program called RACE — Record Activity, Coach to Expectations — for which she was a coordinator.

“The new reps would come in sit down and talk about how their day before went, what they got accomplished, and what they didn’t get accomplished,” she explained, adding that young agents would often leave her office with steam coming out of their ears. “I would then coach them, or yell at them, about what they did and didn’t accomplish.”

Her RACE work was part of what Kane described as one of the more unusual routes to a managing director’s position with Northwestern — most start and stay in sales — but one she believes has effectively prepared for that role. Elaborating, she said her work as a field director for the Springfield office gave her the direct work in sales that she would need to make the leap to the highly entrepreneurial managing director’s post.

“I knew that if I didn’t take that step and gain that experience, I would never move beyond being someone else’s employee, which I was with Paul, and move into an entrepreneurial role,” she explained, adding that, in effect, managing directors, like top agents, are independent contractors.

Steffan thought she was ready to take that step, and be uncomfortable again, in late 2001. That’s when she was assigned the Worcester County office, in Westboro, a facility that had been doing business since the late 1800s, but was, by most accounts, undeveloped territory.

She managed to achieve some growth there, but when the Springfield managing director’s position became available, she sought a return to that office. Part of the reason was the connection to the business community here — she had served on a number of non-profit groups, including Dress for Success, the Women’s Partnership, the Springfield Mentoring Project, and others — but there was also the entrepreneurial drive that Steffan had helped coax.

“He was good at thinking big for us,” she told BusinessWest, adding that the Springfield office was and is much bigger than Worcester’s and possessed, by her estimation, stronger and more attainable growth potential.

And in the six months she’s been at the helm, she’s been hard at work developing strategies to achieve it.

By the Numbers

Most all of them come back to that art and science known as recruiting, she said, adding that in this business, such activity is constant. “It never ends.”

The reason is because of the difficult nature of the work, she continued, adding that if it was easy everyone would want to do it because the rewards can be considerable.

“But it’s not easy … our type of entrepreneurship is particularly difficult because no one wants to talk about the issues we raise,” she said. “Individuals have to be willing, as I like to tell new reps, to acknowledge that they’ll be constantly dealing with other people’s baggage.

“And you have to learn how to be really good at helping when you can help and leading when you can lead, but also identify when ‘that’s their issue’ and leave it on that side of the table and not get crushed and emotionally battered by that,” she said, adding that sales don’t come easily or quickly, and sometimes they don’t come at all.

Identifying individuals with the personality and talent to handle all this is a challenge for all players in this industry, said Kane, noting that changing demographics, specifically the aging of the Baby Boom generation, is adding additional hurdles. Indeed, the average age of agents in this field is 54, she said, noting that the need to replace top talent prompts many companies to rely on essentially taking it from competitors.

Northwestern, which has a younger demographic (the average age of its agents is 42), is one of the few companies left that will devote the time, money, and energy needed to recruit and development young talent.

“We’ll take green kids and groom them,” said Kane, noting that the company has one of the most extensive, and successful, internship programs in the country.

“That’s our secret weapon,” she said, noting that locally, the program involves UMass-Amherst and Western New England College. By the time individuals graduate, they are licensed to sell and have started a book of business.

The company’s approach is obviously effective, she said, noting that, industry-wide, for every 100 individuals recruited, 11 will be retained five years later. For Northwestern, that number is 20, and 30 when its comes to a field of 100 interns.And as she goes about recruiting and developing her team, Kane says she will take a page or two from Steffan’s playbook, but also adopt some of her own insights into professional development.

“People are their own, unique individual selves, and if you don’t honor that, you’re going to drive them away,” she said. “So it can’t be about making them fit your vision of who they should be; it has to be about helping them discover who it is they want to be and then not letting them be comfortable.”

Both current and future agents should benefit from an office-consolidation initiative ongoing at Northwestern, said Kane, noting that people will often use the word satellite to describe the Springfield office, and also the district offices in Greenfield, which became part of the Albany facility, and the Northampton office, which also became part of West Hartford. But that is a bit of a misnomer.

“That’s the wrong word, because the managing director is an independent, solo practitioner,” she explained, adding that some in the Springfield area mistakenly believe her office lost something in the translation when it was joined with West Hartford. “I make my own decisions, and I can grow this office as big as I want to.”

Agents in all the company’s offices should have healthy markets in which to sell, Kane explained, because the need for such products and services will only continue to grow — even if existing and prospective clients don’t know they need them.

“Our industry is so secure in so many ways because of the fact that people’s need for advice, people’s need for a disembodied but yet still-involved third party to look at what they’re doing and help them make good decisions isn’t going away,” she said. “It’s always going to be there.”

Lessons Learned

Kane never made it to the University of Chicago, or the front of a college classroom.

But in her mind, she’s doing what she thought she’d be doing for a living — teaching. Just not in a feudalistic system.

“I teach every day, I explain things to people every day,” she told BusinessWest. “But I’m doing it in an environment where it is all based on merit, and on what you can accomplish — and here, there is no limit to what you can achieve for yourself.

Especially if you get that needed kick when you start to feel comfortable.

George O’Brien can be reached at[email protected]