In Law and Accounting, It’s a Different World

When Rudy D’Agostino entered the accounting profession back in 1985, there was what they called the ‘Big 8.’

When Rudy D’Agostino entered the accounting profession back in 1985, there was what they called the ‘Big 8.’

These were the very large firms that dominated the industry at the time — Arthur Anderson, Arthur Young, Coopers & Lybrand, Deloitte Haskins and Sells, Ernst & Whinney, Peat Marwick Mitchell, Price Waterhouse, and Touche Ross.

“Everyone wanted to work for the Big 8 firms, and there was enormous competition for those jobs,” said D’Agostino, a partner with Holyoke-based Meyers Brothers Kalicka, who got his start at Coopers & Lybrand.

After a series of acquisitions, the Big 8 is now the Big 4 (Deloitte, Ernst & Young, Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler, and PricewaterhouseCoopers), fewer accounting graduates want to work for those giants, and … well, there are fewer accounting graduates in general, a challenge for firms of all sizes.

These are just some of the many changes that have come to the sector, and professional services in general, said D’Agostino and many others we spoke with, who highlighted everything from the way people work to the way people dress to the way firms market themselves — something they couldn’t do in the legal profession, other than the phone book, until 1977. And in accounting, getting Fridays off during the summer, or at least Friday afternoons, has become the norm as firms’ staffs look to recover after a long, seemingly never-ending tax season.

Overall, the biggest change is in how people communicate and a resulting faster pace to the work, said Amy Royal, founder and principal with the Springfield-based Royal Law Firm. She noted that, when she broke into the field in 2000, most correspondence was still by mail. Now, the postage machine sees less use seemingly every month, and very little is actually done by mail.

Instead, much more is being done by email and phone, specifically the cellphone.

Indeed, Royal remembers walking into the office once maybe 15 years ago, and noting, with alarm, how infrequently the office phone had been ringing of late.

“I said to my office manager, ‘do we have a problem? — our office phone isn’t ringing as much,’” she recalled, noting that, after some perspective, she was simply recognizing a trend — people were finding other ways to reach out. And they were doing so at seemingly all hours of the day and night.

Indeed, modern communications technology allows people to reach their accountant or lawyer at any hour, said Jeff Fialky, managing partner of the Springfield-based law firm Bacon Wilson, and, increasingly, they’re doing just that.

Meanwhile, there have been other changes in these fields, including consolidation, especially in accounting, said Patrick Leary, a principal with the Springfield-based firm MP CPAs, noting that many of the smaller firms doing business in the ’80s, ’90s, and earlier this century have been merged into larger firms, a reflection of a broader trend in business.

Jeff Fialky

“We’ve seen substantial consolidation in the banking environments. We have larger and larger and fewer and fewer banks, and the same consolidation across the service industries.”

There are several reasons for this, including the rising costs of technology and retiring Baby Boomers, he noted, but one of the biggest is something that probably couldn’t have been imagined in 1984 — the deepening challenge of finding and retaining talent.

Accounting was never a ‘sexy’ profession, and modern technology has only made it slightly more so, said Leary, adding that this reality, coupled with the fact that a fifth year of college is now required to become a CPA, is leaving fewer people interested in entering the field, at the same when most Baby Boomers are on the doorstep of retirement, if not there already. This has led to firms boosting salaries and sending more work overseas.

Efforts to recruit more students into the field have become a topic of conversation and concern among CPAs and industry groups, said D’Agostino, and greater reliance on internship programs as feeder initiatives.

It’s the same with clerking programs in the legal profession, said Fialky, adding that, overall, law-school enrollment is down, and many firms face challenges with keeping talent in the pipeline.

Case in Point

It’s not exactly what you would call a pressing matter — not like some of those other challenges mentioned above — but one of the challenges facing law firms today is deciding what to with their libraries.

Once an important part of any firm’s operation, they are now all but obsolete, used by only the occasional old-timer now that every piece of information available in those books and journals can be found online, said Royal, adding that, at most firms, law books are decoration — and an enduring background for photos.

Fialky agreed, noting that the demise of libraries is just one of many changes to the profession. Others include the now-24/7 nature of the work, the desire among clients for information immediately — not the next day or even in a few hours, as was once the case — and even the work that lawyers are doing, work that reflects shifts in the market and also movement toward lawyers being more generalists than they are specialists.

Amy Royal

“For a long time, I resisted putting my cell phone on my business card. Post-COVID, that became a necessity, and now people will just call me on my cell or text because they know they can get me.”

“I’m a transactional attorney; 25 years ago, transactional attorneys were not handling M&A transactions and purchases and sales and private equity,” he said. “That’s something we’ve seen become more prominent, especially in our market, over the past 15 years or so, as we’ve seen these maturing, multi-generational companies that have contemplated their outcome being that it’s a matured asset, and their contemplating sale to, in many circumstances, a private-equity-funded purchaser.

“And this has certainly changed the marketplace,” Fialky went on. “We’ve seen substantial consolidation in the banking environments. We have larger and larger and fewer and fewer banks, and the same consolidation across the service industries — not only in law, but in accounting, architecture, landscape architecture, and other sectors.”

But perhaps the biggest change to come to this sector involves technology and how it has changed the pace of work.

Royal noted that lawyers have never exactly been 9-to-5 professionals, and now, they are far less so, with calls, texts, and emails coming at all hours of the day, and with those on the other end expecting an immediate reply.

“For a long time, I resisted putting my cell phone on my business card,” she said. “Post-COVID, that became a necessity, and now people will just call me on my cell or text because they know they can get me.”

Fialky agreed. “The pace has increased precipitously; the volume of correspondence has increased exponentially. In the course of a day, it’s not uncommon, at least in my experience and in my practice, to receive hundreds of correspondences, and those are texts, calls to my cell phone, calls to my hard line, and more, and a lot of that is transferred direct to attorney.”

Adding Things Up

As he talked about his profession, Leary said it was never just about adding up numbers and being a proverbial ‘bean counter.’

There was always a consulting component to the work, he said, adding that now, there is much more of this kind of work, as software has taken over some of the tasks handled with the old calculator that still sits on his desk but is rarely used.

Patrick Leary

“It’s fascinating what you can get involved with in public accounting today, whether it’s forensic accounting or foreign taxation issues and so forth.”

“Today, most businesses, regardless of size, have some accounting software, so you’re getting information from them that’s already compiled and put together, so they’re relying on us for more strategic analysis of those numbers,” he explained. “You’re not questioning whether two plus two equals four; now it’s ‘let’s see what four means.’

“It’s a higher level of skill than what you needed before,” he went on, adding that this shift is one of many to come to the industry.

Another is how the work is done. Indeed, years ago, said D’Agostino, much more time was spent with the client, in person. Today, there is still some face-to-face interaction, obviously, but much more is done by Zoom or over the phone. And those face-to-face meetings are much different.

Leary agreed.

“If we were going to audit ABC Company, we’d back up last year’s paper files and head over there,” he said. “You would spend a couple of weeks with a client, meeting with them, going through their records, pulling invoices, and doing reports. You’d spend a few weeks there — which I really liked, being out of the office, meeting with clients — and building that relationship. And you got a workout because you’d be hauling loads of paper. Today, you’re going out with your laptop, and you’re not necessarily going out to see clients.”

Still another change to come to this field, as noted earlier, is the fact that fewer people are choosing to enter it.

“The accounting field has been experiencing a decline nationally because people who are driven by numbers are leaning more toward the software industry,” Leary said. “And the profession is certainly looking to change that; you can have an excellent career in accounting, because it goes well beyond simple bookkeeping. It’s fascinating what you can get involved with in public accounting today, whether it’s forensic accounting or foreign taxation issues and so forth.”

Rudy D’Agostino

“It really hit home during COVID, and it has only continued since — there are just not enough professionals coming into the workforce.”

D’Agostino agreed. He noted that the required fifth year of college, compensation that is less competitive than some other fields, and a general interest among young people for something sexier than what they perceive accounting to be has led to what is becoming a critical problem for the industry.

“It really hit home during COVID, and it has only continued since — there are just not enough professionals coming into the workforce,” he told BusinessWest. “So accounting firms have to think outside the box to get things done — and also to keep professionals here, which has necessitated being creative, compensation increases, and, with some firms, outsourcing work to other countries.”

One initiative that has helped put young professionals in the pipeline at MBK is an internship program, D’Agostino went on, adding that the firm has four or five interns that come on board annually, and maybe one or two of these will join the firm when they graduate.

“That’s a way to introduce students to the work they will be doing and get them into our firm,” he said. “And we have a pretty good success rate.”

Despite this success, workforce issues will continue into the future, said those we spoke with, creating a greater reliance on technology, automation, and, increasingly, AI to get the work done, leaving accountants with more time to do analysis and consulting.

“There are routine tasks that will get taken over by AI, such as data entry, which can be automated to some extent,” Leary said. “And that provides the time and the tools to analyze data for clients much better. Rather than spending your time keying in data, you’re taking a hard look at it and understanding what those numbers are telling you.”

Bottom Line

When asked to look ahead and project what might happen next within the legal sector, Royal started by saying that, if she was asked that question 25 years ago, she could not possibly have predicted what her world would like today.

That’s a world where most meetings are conducted by Zoom, where lawyers and accountants work remotely in some cases and wear jeans to work when they’re not in court or visiting clients, where the office phone doesn’t ring nearly as much, and where clients’ names come up on cellphones at 10 p.m. — and even 3 a.m.

This is the new reality for those in professional services, she said, joking that maybe what will come next is a shift back to the way things were.

That is certainly not likely. What is likely is that law libraries and those old-fashioned adding machines will become more obsolete and more office decoration than anything else.

Allison Ebner recalls that, when she first entered the workplace just over 30 years ago, the overriding question still concerned what the employee could do for the employer.

Allison Ebner recalls that, when she first entered the workplace just over 30 years ago, the overriding question still concerned what the employee could do for the employer.

On Jan. 22, 1984, a good deal of the U.S. watched — for the only time, because it never aired again — a commercial that was, in many ways, more interesting than the beatdown the Los Angeles Raiders were putting on the Washington Redskins in Super Bowl XVIII.

On Jan. 22, 1984, a good deal of the U.S. watched — for the only time, because it never aired again — a commercial that was, in many ways, more interesting than the beatdown the Los Angeles Raiders were putting on the Washington Redskins in Super Bowl XVIII.

When Rudy D’Agostino entered the accounting profession back in 1985, there was what they called the ‘Big 8.’

When Rudy D’Agostino entered the accounting profession back in 1985, there was what they called the ‘Big 8.’

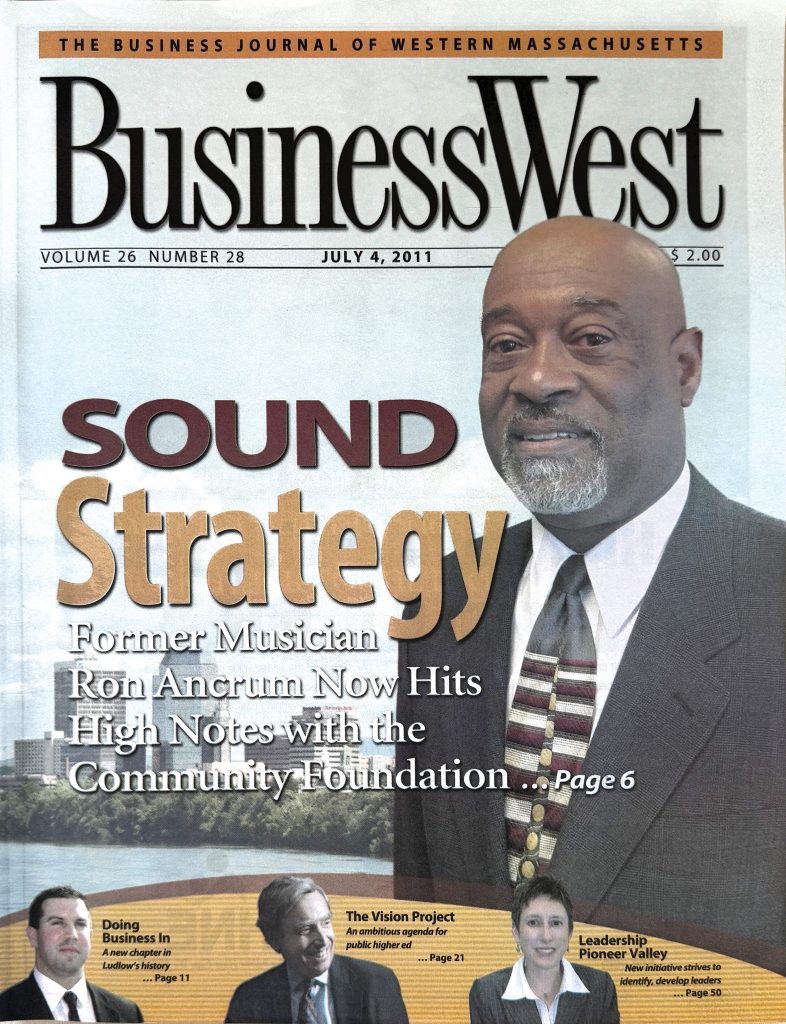

The Community Foundation of Western Massachusetts has been funding the work of charities and nonprofits across the region since 1991. And its overriding mission hasn’t changed.

The Community Foundation of Western Massachusetts has been funding the work of charities and nonprofits across the region since 1991. And its overriding mission hasn’t changed.

Rick Sullivan calls manufacturing the “invisible backbone” of the Western Mass. economy.

Rick Sullivan calls manufacturing the “invisible backbone” of the Western Mass. economy.

At the recent ceremony that officially installed him as chancellor of UMass Amherst, Javier Reyes noted that attitudes about higher education are changing, while rapid advancements in technology, with artificial intelligence at the center, are forcing colleges and universities to find new ways to meet their obligations.

At the recent ceremony that officially installed him as chancellor of UMass Amherst, Javier Reyes noted that attitudes about higher education are changing, while rapid advancements in technology, with artificial intelligence at the center, are forcing colleges and universities to find new ways to meet their obligations.

Twenty years ago, in the issue commemorating BusinessWest’s 20th anniversary, area hospital leaders talked about what had changed the most over two decades, and they all mentioned the same thing: a shortening of hospital stays, with procedures that once required a several-night stayover now requiring only one — or none at all.

Twenty years ago, in the issue commemorating BusinessWest’s 20th anniversary, area hospital leaders talked about what had changed the most over two decades, and they all mentioned the same thing: a shortening of hospital stays, with procedures that once required a several-night stayover now requiring only one — or none at all.

When she first started working for Merrill Lynch in 1985, Pat Grenier had a desk, a phone, a phone book, and a street directory. And there was a lot of cold calling.

When she first started working for Merrill Lynch in 1985, Pat Grenier had a desk, a phone, a phone book, and a street directory. And there was a lot of cold calling.

When you’ve been building things for as long as Daniel O’Connell’s Sons (DOC) has, well … sometimes you enjoy the sequel.

When you’ve been building things for as long as Daniel O’Connell’s Sons (DOC) has, well … sometimes you enjoy the sequel.

When Jack Dill, president of Colebrook Realty Services, arrived in downtown Springfield in the mid-’70s, it was a different world and a much different city.

When Jack Dill, president of Colebrook Realty Services, arrived in downtown Springfield in the mid-’70s, it was a different world and a much different city.

Tom Senecal used some hard numbers to detail what is perhaps the biggest change in the banking industry over the past four decades.

Tom Senecal used some hard numbers to detail what is perhaps the biggest change in the banking industry over the past four decades.

The Western Mass. region has a strong tradition of entrepreneurship that goes back more than three centuries.

The Western Mass. region has a strong tradition of entrepreneurship that goes back more than three centuries.