They’ve Shared a Lifetime Working for Social Change

Frederick Hurst clearly recalls where he was the April afternoon in 1968 when Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed. It was a job interview — a job he decided not to take.

Frederick Hurst clearly recalls where he was the April afternoon in 1968 when Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed. It was a job interview — a job he decided not to take.

That day, he said, changed the course of his life, and that of his wife, Marjorie. The trajectory of those lives has been a winding one, with many stops along the way, but one common thread — a constant focus on making a difference, in myriad ways.

For the past 15 years, the most visible vehicle for that change has been An African American Point of View, the ‘newsmagazine,’ as Rick calls it, that blends community news with often-unsparing commentary, every word of it edited by Marjorie. We’ll let his note in a recent issue explain the dynamic.

“We didn’t start this paper without knowing what we want to accomplish. We knew where we wanted to go in terms of content and impact. And we still feel we provide a point of view that is not provided anywhere else.”

“Like any journalist, I have an editor who pushes back at me. She pisses me off sometimes, but I often acquiesce. I’m not easy. She often recoils at stuff that truly expresses what I mean to say even though it might upset some folks. I am most responsive when she can show me a milder way to say the same thing and less responsive when she suggests a change simply because, without it, someone will get mad. I write it as I see it. And sometimes, I want to make someone mad because it is a legitimate part of my message and it tells the story best.”

“We didn’t start this paper without knowing what we want to accomplish,” Rick told BusinessWest. “We knew where we wanted to go in terms of content and impact. And we still feel we provide a point of view that is not provided anywhere else.”

It’s a perspective that remains badly needed, he added.

“The African-American point of view is so diluted in every medium you can find around here. I don’t think that has been malicious; I just think folks generally don’t understand what that means, even though they do the best they can,” he continued. “Sometimes I write to educate, sometimes I write to provoke, and sometimes I write to just express my opinion.”

Pointing out ways that political, educational, and economic infrastructures present barriers to success for the black community is nothing new to the Hursts.

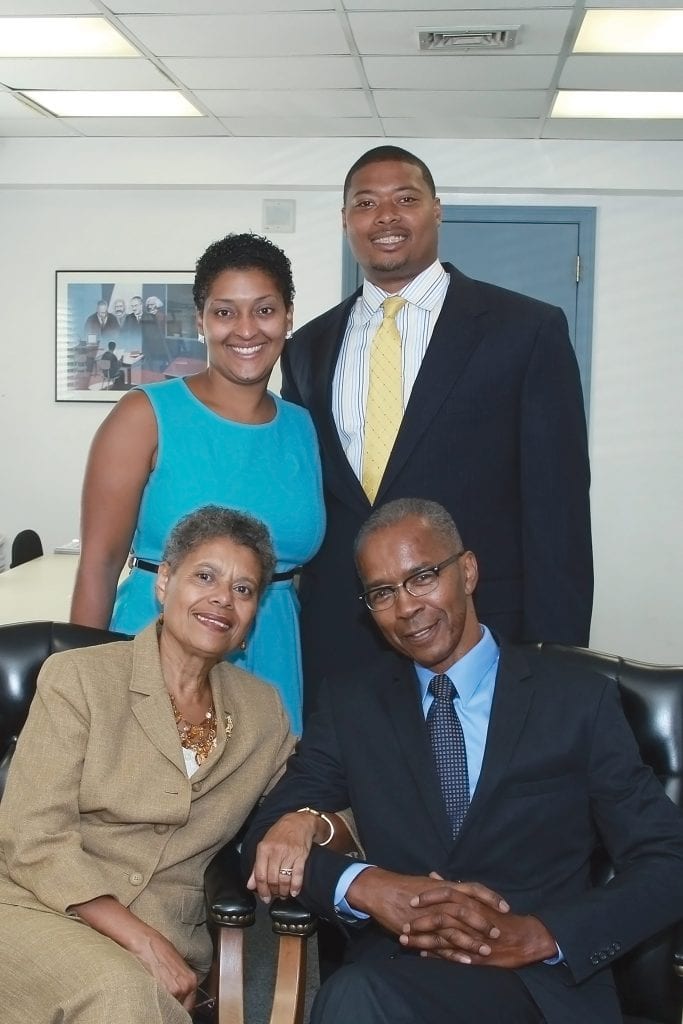

Marjorie and Rick Hurst are gratified that their son Justin and daughter-in-law Denise — who serve on Springfield’s City Council and School Committee, respectively — have followed their example of civic involvement.

“These things need to be discussed without equivocation,” Rick continued. “And most people I know — good people — are equivocal. They’ve been raised to be equivocal, and approach things like race with such delicacy that the story doesn’t get out there. One way we can make a solid impact as a newspaper is to deal with these race issues unequivocally. And I think we’re having an impact. Sometimes my good friends get mad at me — but it doesn’t bother me. I learned, if you have another point of view, write it, and we’ll print it.”

Marjorie noted that the newspaper had long been on the couple’s five-year plan — for way more than five years, actually — before they actually launched it in 2003.

“It was always part of what we were going to do,” she said. “He always had something to say, always had thoughts, always had ideas and a need to express them.”

And a need for an editor — even when they were dating as teenagers and engaged as college students.

“I’d send her love letters, and she’d send them back with corrections in red,” he laughed. “And she’s still doing that with anything else I write.”

A Life Together

In fact, the Hursts have known each other from their days as Buckingham Junior High School students in Springfield. Marjorie went to the High School of Commerce, Rick to Technical High School, and they had been dating for five years when they decided to tie the knot as undergrads at Howard University in Washington, D.C. in 1967.

“I was planning to go into speech therapy and audiology,” she recalled. “I had started out in journalism, but decided not to do that. It felt too intrusive to ask people all these questions.”

King’s death when the couple were seniors at Howard palpably altered both their career paths. An economics major with his eye on law school, Rick was sitting at a table with executives from D.C.-based Riggs National Bank, who were making him an offer to manage their trust department — and offering to pay his way through law school — when he heard King had been shot.

“People came running in, screaming and hollering — everyone was all upset,” he recalled. “It changed everything. I listened and was very cool, but I knew I wasn’t going to work for a bank, and we made a decision to come back to Springfield.”

“Most people I know — good people — are equivocal. They’ve been raised to be equivocal, and approach things like race with such delicacy that the story doesn’t get out there.”

With a new sense of mission, Rick got involved in poverty and unemployment programs, and they both taught school. He was recruited by Digital Equipment Corp. to run its planning department in Springfield and did well there for several years, but grew frustrated by the steady flow of white employees being promoted ahead of him. They both attended a graduate program at UMass, after which time an intriguing opportunity arose in Chicago.

It was an experimental, relatively new school on the west side of the city — a rough area to say the least — called Daniel Hale Williams University. Rick became facilities manager in 1975, while Marjorie worked as registrar.

“We sold our house, packed up our furniture, and moved to Oak Park,” he recalled. “The school had campuses all over the west side and south side, into the projects. We struggled to make that thing survive — but it didn’t survive. We had cashed in everything, and we were out in the middle of the country, when the school went bankrupt. Both of us were out of a job, and Marge was pregnant with our third child, Justin.”

That was the low point in their early part of their marriage, but again, they were energized by a planned return to Springfield. This time, they turned to law, Rick’s original goal as an undergrad at Howard. He enrolled at DePaul University School of Law — also working part-time while Marjorie worked full-time — and then both returned to Springfield, where she enrolled in Western New England College School of Law.

Rick Hurst says he writes to both educate and provoke — because sometimes people need a little provocation.

She opened a law office with a friend, while then-Gov. Mike Dukakis appointed Rick a commissioner at the Mass. Commission on Discrimination, overseeing 171 communities in the western half of the state for the next nine years.

“It was a very powerful commission then,” he said, explaining that MCAD had a judicial unit and a civil-rights unit. The latter, which no longer exists, allowed commissioners to essentially police every municipality and require them to develop diversity programs for employment, housing, and contract compliance — and authority to bring charges if they didn’t comply.

Holyoke and Springfield were both recalcitrant when it came to instituting such programs, he noted, and Holyoke has been more progressive over the years than Springfield, which Hurst feels remains somewhat stuck in old-school politics when it comes to systemic change.

“It was a great time in my life. We saw some positive changes,” he said. “And when I left, I went with my love” — specifically, to join her in the law firm that would eventually be known as Hurst and Hurst, P.C.

“It was an interesting time,” Marge said regarding those early years. “We just started off young and involved, and we continued to be involved. We got involved in civil rights. We were part of high-school walkouts over the lack of minority teachers and a black-focused curriculum. We set up an alternative school. We’ve always been extremely active and dedicated to moving the ball forward in whatever way we could. But we’ve always worked closely together and been supportive of each other, and there’s always been the feeling we’re equal partners.”

Hot Off the Presses

By the turn of the century, they both agreed their newspaper idea couldn’t stay on the five-year plan forever. So, in 2003, they took the plunge — with a little extra motivation from a black newspaper based in Framingham that was sniffing around Springfield. “That sped us up,” Rick said. “We knew we had a better product.”

The paper was originally published quarterly, then bimonthly in its second year, then monthly in its third, which it remains to this day. When the Great Recession hit, the paper struggled somewhat — advertisers began pulling back, loath to spend money during those difficult years — but Af-Am Point of View survived and eventually thrived, rebranding as a newsmagazine and pouring resources into producing more — and more diverse — content, while also developing an online presence.

“I’d send her love letters, and she’d send them back with corrections in red. And she’s still doing that with anything else I write.”

“We entered the market as African-American emphasis paper, but we always knew we’d expand and broaden it out,” Rick said. “We felt the paper would never grow in reader interest without a diversity of writers, to make it interesting to everybody.”

The Hursts celebrate Marjorie’s election to the Springfield School Committee — she was the top vote getter — in this 1997 photo from the Union-News.

Indeed, those writers represent diverse races, genders, and ages, too — in fact, a recent issue featured an essay by the Hursts’ 12-year-old grandson, Tristin.

Through it all, Rick has never been one to pull punches, whether speaking broadly about systemic racism in the U.S. or calling out local leaders on political matters.

“I’m more the warrior type than Marge,” he said. “Not in a wild and crazy way — I’m more measured than that. But I fight for change. I understand what change means. All my adult life, I’ve been fighting for political change, broader cultural change in the way people think. And the paper has made a difference. I think we’ve impacted the way people see black people and the way black people see themselves. I know we’re not there yet, but nothing makes me feel better than to know we have started something in that direction that’s meaningful.”

The Hursts have a long political history in the city, including Rick’s unsuccessful effort in the mayoral race of 1969, and City Council bids after that. Meanwhile, Marjorie served 12 years on the Springfield School Committee. Their youngest son, Justin, has followed suit over the past few years, most recently being named president of the City Council, while his wife, Denise, serves on the School Committee.

That legacy is gratifying for Marjorie, who had her kids knocking on doors from an early age supporting local candidates for office. “They had a history of being active and involved in politics.”

“They were very much involved,” Rick added. “We were sophisticated — we could break wards down, break streets down; we understood the value of door to door, face to face. They grew up with that in their heads, and the work was natural to them. But they take it to a new level with technology.”

That civic investment by the next generation is a source of pride, he added.

“That’s what I live for. I want to see my kids get involved in the body politic, and not just them. A whole lot of other minorities, black, Hispanic — and women, too — should get involved so Springfield is run like it should be run.”

Marjorie calls Rick conservative when it comes to his feelings about family structure, but he considers their family proof that a two-parent home — with two educated parents, no less — gives kids a great advantage in life. Their daughter and oldest child, Tiffani, is an assistant to the public defender in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, following years as a federal appellate attorney in Las Vegas. Their first son, Frederick Jr., has a CPA background and works for the public school system locally.

“I made a promise to myself, years before I met Marge, that I’d meet a good woman who’d want to marry me, and I’d stay with her for the rest of my days,” Rick said. “I’ve always preached it to my kids — take your time, find a good woman you’re compatible with, and commit to stay with her for the rest of your life and raise your kids right.”

He explained that Marjorie represented something aspirational to him, whose wisdom he has long relied on.

“I’m more the warrior type than Marge. Not in a wild and crazy way — I’m more measured than that. But I fight for change. I understand what change means. All my adult life, I’ve been fighting for political change, broader cultural change in the way people think.”

“I’m a kid from the hood; I really am — fisticuffs and gambling and all that,” he said. “When I made a decision to go to college, I had all that baggage. And at every critical point in my life, I can point to Marge being there as incredible support. Whether I would have made it anyway, I don’t know. But, my God, most people who came up with me … I’ve got more dead than alive, and many of them died decades ago.”

Even at Howard, he vascillated in his goals and considered dropping out to join his brother in the Army. “But she helped me struggle through, and I finished college. If I ever write my story, it’ll be a story about Marge.”

The Next Chapter

But Rick has written a book already: A History of Blind Industries and Services of Maryland, the century-spanning account of a program in Maryland dedicated to putting blind people to work — a success story that reflects his own philosophy about how government programs should support, but never replace, organic economic development in a community.

“You’ve got to introduce an economic-development element into every program you put on the table, or they’re all going to fail,” he said “These people figured out how you do it, how to integrate government money into private operations and grow the private sector much bigger than the original government investment.”

In some ways, the Hursts’ life together has been a microcosm of that kind of growth, constantly planting seeds — from a newspaper influencing public opinion to the development of black-centric curriculum in the public schools, to the raising up of future generations who will continue making a difference.

“Justin and Denise surround themselves with people of all races; they’re comfortable with everyone,” Marge said of the two Hurst family members with the most public profile these days. “That gives you hope for the future — how seamlessly they move into the fabric of the city, into all areas of the city. It makes you feel good that you might have contributed to an element of change in the city. So we’re extremely proud to be here at this point in time and still be contributing through the newspaper.”

Not that the work is ever truly done, Rick was quick to add, arguing that Springfield will never grow to political maturity until it fully shakes off its history of crony politics and embraces more diversity and openness to change. “I know it sounds idealistic, but change never came about through people who weren’t idealistic. The only way you change that stuff is to keep picking at it.”

He admires a quote by Thomas Jefferson — a man, it must be said, with his own racial complexities — who once noted that, if he had to choose between a government without newspapers or newspapers without government, he would not hesitate to choose the latter.

“That’s the power of the media,” Rick said. “Jefferson knew what he was talking about. If we didn’t have the press today, we’d be well on our way to a dictatorship. I’ve come to understand the power of the press.

“We’ve had an impact in that respect,” he went on. “The Hursts never set out to be prominent. We set out to make a difference, and we have made a difference. And that impact will continue long after we’re gone.”

Joseph Bednar can be reached at [email protected]