VA Hospital Nears a Century of Service to Those Who Have Served

On the Front Lines

Early aerial photo of the VA Hospital in Leeds, Mass.

Gordon Tatro enjoys telling the story about how the sprawling Veterans Administration facility in Leeds came to be built there.

The prevailing theory, said Tatro, who worked in Engineering at what is now the VA Central Western Massachusetts Healthcare System for 20 years and currently serves as its unofficial historian, is that the site on a hilltop in rural Leeds was chosen because it would offer an ideal setting for treatment and recuperation for those suffering from tuberculosis — one of its main missions, along with treatment for what was then called shell shock and other mental disorders.

And while some of that may be true, politics probably had a lot more to do with the decision than topography.

“President Warren G. Harding came out and said, ‘stop looking for places … we’re going to put it in Northampton,’” said Tatro, acknowledging that he was no doubt paraphrasing the commander in chief, “‘because Calvin Coolidge is my vice president and he lives in Florence, and we want it to be in or around Florence.’”

Nearly 95 years later — May 12 is the official anniversary date — it is still there. The specific assignment has changed somewhat — indeed, tuberculosis is certainly no longer one of the primary functions — but the basic mission has not: to provide important healthcare services to veterans.

Overall, there has been an ongoing transformation from mostly inpatient care to a mix of inpatient and outpatient, with a continued focus on behavioral-health services.

“We’re more of a managed-care facility now,” said Andrew McMahon, associate director of the facility, adding that the hospital provides services ranging from gerontology to extended care and rehabilitation; from behavioral-health services to primary care; from pharmacy to nutrition and food services. Individual programs range from MOVE!, a weight-management program for veterans, to services designed specifically for women veterans, including reproductive services and comprehensive primary care.

Andrew McMahon says the VA facility in Leeds is undergoing a massive renovation and modernization initiative scheduled to be completed by the 100th anniversary in 2024.

“When this facility was established, the mission of the VA was much different than it is today,” McMahon told BusinessWest. “We were a stand-alone campus in a rural part of the state that had 1,000 beds and where veterans went for the rest of their lives.

“Now, we are one facility within a network of eight serving Central and Western Massachusetts. We have this beautiful, 100-year-old campus, but the needs of today’s veterans are changing — they need convenience, primary care, and specialty care, and we’re trying to establish those services in the areas where the veterans live, primarily Worcester and Springfield.”

Elaborating, he said that, as the 100th anniversary of the Leeds facility in 2024 approaches, the hospital is in the midst of a large, multi-faceted expansion and renovation project designed to maximize its existing facilities and enable it to continue in its role as a “place of mental-health excellence for all of New England,” as McMahon put it, and also a center for geriatric care and administration of the broad VA Central Western Massachusetts Healthcare System.

By the 100th-birthday celebration, more than $100 million will have been invested in the campus, known colloquially as ‘the Hill,’ or Bear Hill (yes, black bears can be seen wandering the grounds now and then), said McMahon, adding that an ongoing evolution of the campus will continue into the next century.

“President Warren G. Harding came out and said, ‘stop looking for places … we’re going to put it in Northampton, because Calvin Coolidge is my vice president and he lives in Florence, and we want it to be in or around Florence.’”

Round-number anniversaries — and those not quite so round, like this year’s 95th — provide an opportunity to pause, reflect, look back, and also look ahead. And for this issue, BusinessWest asked McMahon and Tatro to do just that.

History Lessons

Tatro told BusinessWest that, with the centennial looming, administrators at the hospital have issued a call for memorabilia related to the facility’s first 100 years of operation. The request, in the form of a flyer mailed to a host of constituencies, coincides with plans to convert one of the old residential buildings erected on the complex (specifically the one that the hospital directors lived in) into a museum.

The flyer states that, in addition to old photographs, those conducting this search are looking for some specific objects, such as items from the old VA marching band, including uniforms and instruments; anything to do with the VA baseball team, known, appropriately enough, as the Hilltoppers, who played on a diamond in the center of the campus visible in aerial photos of the hospital; any of the eight ornate lanterns that graced the grounds; toys made by the veterans who lived and were cared for at the facility; copies of the different newspapers printed at the site, including the first one, the Summit Observer; and more.

Collectively, these requested items speak to how the VA hospital was — and still is — more than a cluster of buildings at the top of a hill; it was and is a community.

The oval at the VA complex has seen a good deal of change over the years. Current initiatives involve bringing more specialty care facilities to that cluster of buildings, bringing additional convenience to veterans.

“It was like a town or a city,” said Tatro, noting that the original campus was nearly three times as large as it is now, and many administrators not only worked there but lived there as well. “There was a pig farm, veterans grew their own food, there were minstrel shows, a marching band, a radio station … it really was a community.

“In that era, everyone had a baseball team, and we played all those teams,” he said, noting that the squad was comprised of employees. “The silk mill (in Northampton) had one, other companies had them; I’ve found hundreds of articles about the baseball team.”

This ‘community’ look and feel has prevailed, by and large, since the facility opened to considerable fanfare that May day in 1924. Calvin Coolidge, who by then was president (Harding died in office in 1923) was not in attendance, but many luminaries were, including Gen. Frank Hines, director of the U.S. Veterans Bureau.

He set the tone for the decades to come with comments recorded by the Daily Hampshire Gazette and found during one of Gordon’s countless trips to Forbes Library on the campus of Smith College. “President Coolidge has well stated that there is no duty imposed upon us of greater importance than prompt and adequate care of our disabled. And every reasonable effort will be made in that direction. I consider it the duty of those in charge of the veterans’ bureau hospitals to bring about a management and an administration of professional ability in such a manner as to recover many of those whose care is entrusted to them.”

“It was like a town or a city. There was a pig farm, veterans grew their own food, there were minstrel shows, a marching band, a radio station … it really was a community.”

The facility was one of 19 built in the years after World War I to care for the veterans injured, physically or mentally, by that conflict, said Gordon, adding that the need for such hospitals was acute.

“There was a drive in Congress to get the veterans returning from World War I off the streets,” he said. “They were literally hanging around; they had no place else to go. Public health-service hospitals couldn’t handle it, and the Bureau of War Risk Insurance couldn’t handle the cost, and I guess Congress just got pushed to the point where it had to do something.”

That ‘something’ was the Langley bill — actually, there were two Langley bills — that appropriated funds to build hospitals across the country and absorb the public health-service hospitals into the Veterans Bureau Assoc.

The site in Leeds was one of many considered for a facility to serve this region, including a tissue-making mill in Becket, said Tatro, but, as he mentioned, the birthplace of the sitting vice president ultimately played a large role in where the steam shovels were sent. And those shovels eventually took roughly 12 feet off the top of the top of the hill and pushed it over the side, he told BusinessWest.

As noted earlier, the facility specialized in treating veterans suffering from tuberculosis and mental disorders, especially shell shock, or what is now known as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the early years, there were 300 to 500 veterans essentially living in the wards of the hospital, with those numbers climbing to well over 1,000 just after World War II, said Tatro.

Gordon Tatro, the unofficial historian at the VA hospital, says the facility is not merely a collection of buildings on a hill, but a community.

With tuberculosis patients, those providing care tried to keep their patients active and moving with a range of sports and games ranging from bowling to swimming to fishing in ponds stocked by a local sportsman’s club, or so Tatro has learned through his research.

As for those with mental-health disorders, Tatro said, in the decades just after the hospital was built, little was known about how to treat those with conditions such as shell shock, depression, and schizophrenia, and thus there was research, experimentation, and learning.

This added up to what would have to be considered, in retrospect, one of the darker periods in the facility’s history, when pre-frontal lobotomies and electric-shock therapy was used to help treat veterans, a practice that was halted in the late ’40s or early ’50s, he said, adding that this is one period he is still researching.

Battle Tested

Over the past several decades, there has been a slow and ongoing shift from inpatient care to outpatient care, said McMahon, who, in his role as associate director, is chief of all operations. He added that there are still inpatient wards at the hospital, and it retains its role as the primary regional provider of mental-health services for veterans.

But there is now a much broader array of services provided at the facility, and for a constituency that includes a few World War II and Korean War veterans, but is now dominated by Vietnam-era vets and those who served in both Gulf wars.

Overall, more than 28,000 individuals receive care through the system, which, as noted, includes both Central and Western Mass. and eight clinics across that broad area. The system measures ‘encounters’ — individual visits to a clinic — and there were more than 350,000 encounters last year.

The reasons for such visits varied, but collectively they speak to how the hospital in Leeds has evolved over the years while remaining true to its original mission, said McMahon.

“We haven’t really downshifted in our inpatient mental health — that’s an area of strength for the VA, and we continue to invest in that area,” he explained. “But in geriatrics, we’re looking to expand our nursing-home footprint, and hopefully double the size of those facilities by the time the 100th comes around — we have 30 beds now, and we’re looking to add maybe 30 more.”

McMahon, an Air Force veteran, said he’s been with the VA hospital for more than seven years now after a stint at Northampton-based defense contractor Kollmorgen. He saw it is a chance to take his career in a different, more meaningful direction.

“To get over into this area and serve the veterans … it’s a job that has a mission behind it,” he told BusinessWest. “It’s more than a paycheck.”

That mission has always been to provide quality care to those who have served, and today, as noted, the mission is evolving. So is the campus itself, he said, adding that ongoing work is aimed at maximizing resources and modernizing facilities, but also preserving the original look of the campus.

Current projects include renovation of what’s known as Building 9, vacant for roughly 15 years, into a new inpatient PTSD facility, with those services being moved from Building 8, an initiative started more than two years ago and now nearing its conclusion.

The new facility will be larger and will enable the VA hospital to extend PTSD care to women through the creation of a dedicated ward for that constituency.

Meanwhile, another ongoing project involves renovation of a portion of Building 4. That initiative includes creation of a new specialty-care floor, a $6 million project that will include optometry clinics, podiatry services, cardiology, and more.

Set to move off the drawing board is another major initiative, a $15 million project to renovate long-vacant Building 20 and move a host of administrative offices into that facility, leaving essentially the entire ‘Hill’ complex for patient care and mental-health services.

“We’re going to get HR, engineering, and other administrative offices down to Building 20 and expand our mental-health facilities around the oval,” McMahon said, referring to the cluster of buildings in the center of the campus. “There’s $40 million in construction going on at present, and by the end the this year, we expect that number to be closer to $60 million.

“There’s a lot of construction going on right now,” he went on. “But things will look good for the 100th.”

That includes the planned museum. The search goes on for items to be displayed in that facility, said Tatro, adding that he and others are working to assemble a collection that will tell the whole story of this remarkable medical facility that became a community.

Branches of Service

Tatro told BusinessWest he’s been doing extensive research on the history of the Hill since he retired several years ago. He’s put together thick binders of photographs and newspaper clippings — there’s one with stories just from the Gazette that’s half a foot thick — as well as some smaller booklets on individual subjects and personalities.

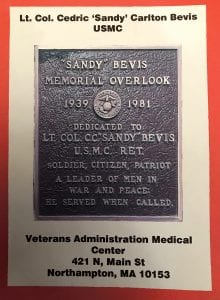

Including one Cedric (Sandy) Bevis.

There’s a memorial stone erected to him in what’s known as Overlook Park, created with the help of that 12 feet of earth scraped off the top of the hill. Tatro found it while out on one of his many walks over the grounds, and commenced trying to find out who Bevis was (he died in 1981) and why there was a stone erected in his honor.

But no one seemed to know.

So Tatro commenced digging and found out that Bevis was a Marine officer who served in Vietnam as a helicopter pilot. He had been shot down more than once but survived. After attaining the rank of lieutenant colonel, he left the service in June 1971, married, and settled in the Florence area. As a Marine Reservist, he got involved with a Vietnam veterans organization called ComVets (short for Combat Veterans) at the VA Hospital and was elected its first president.

“He was honored for his impact on other Marines who were part of ComVets, and they initiated and obtained a plaque for him,” said Tatro, adding that the saga of Sandy Bevis is one of thousands of individual stories written over the past 95 years. And those at the VA facility are going about the process of writing thousands more.

The last line on Bevis’ plaque reads, “He served when called.” So did all those all others who have come to the Hill since the gates opened in 1924. That’s why it was built, and that’s why it’s readying itself for a second century of service.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]