Community Health: Dr. Molly Senn-McNally

This Pediatrician Has Escalated the Fight Against Toxic Stress

Molly Senn-McNally

Dani Fine Photography

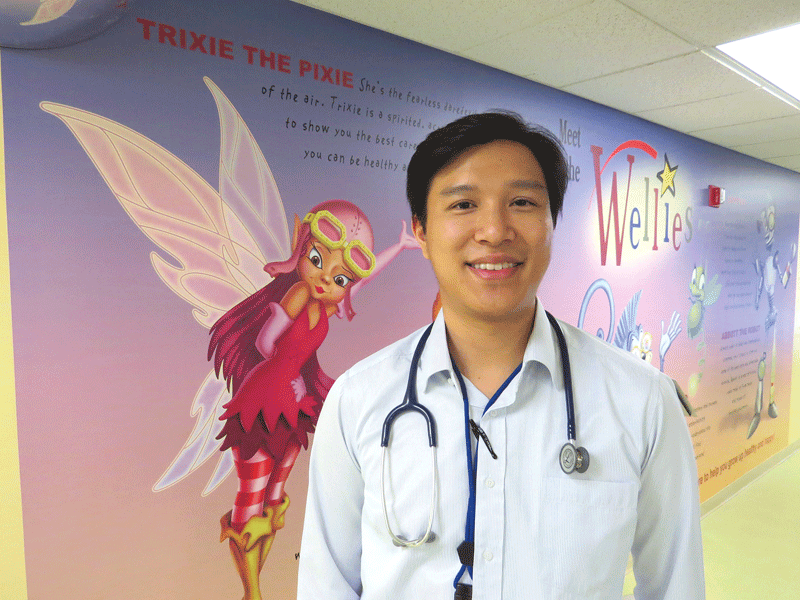

Dr. James Li remembers his heart rate quickening as the “police officer” moved toward him and his two “siblings.”

That’s how real it all was, he told BusinessWest.

But those words are within quotation marks because none of this actually was real; rather, it was a simulation — a poverty-simulation seminar, to be more precise.

Li, a general pediatric resident working at the Baystate High Street Health Center, was playing the middle child in this exercise. His “family,” like many in Springfield that actually come under his care, was living below the poverty line — well below it. And one of the things Li learned very quickly as he acted out his role was that, when the police enter the picture, bad things are probably about to happen — such as children being taken away for suspected neglect.

And that’s why he felt his heart rate spike when a man who was just playing his role as a police officer moved onto the scene.

“I actively told my quote-unquote siblings that maybe we should walk this way to get away from the police officers,” Li recalled while gesturing with his hands to show what he meant. “That was the moment when the simulation became real for me.”

Making such experiences as real as possible is now part of the broad job description for Dr. Molly Senn-McNally, a pediatrician, Springfield’s school physician, and continuity clinic director for the Baystate Pediatric Residency Program. She has made the poverty simulation part of the orientation for Baystate residents, and also part of very comprehensive efforts to help young physicians better care for people living in poverty by making them fully cognizant of all the challenges facing those in this constituency.

Molly is dedicated to the care of children and families who live in poverty-stricken areas of Springfield.”

And that’s only one of many initiatives she’s involved with that so impressed the judges that Senn-McNally was the high scorer in the Healthcare Heroes category known as Community Health.

Others include everything from the introduction of substance-abuse screenings in Springfield schools to an integrated behavioral-health system at the High Street clinic, to ongoing efforts to establish a diaper bank at that facility to assist those struggling mightily to make ends meet.

“Molly is dedicated to the care of children and families who live in poverty-stricken areas of Springfield,” said John O’Reilly, chief of General Pediatrics at Baystate Health, who nominated her. “She understands that social determinants of health have a great impact on the health and well-being of our families, and she has been working hard to decrease the impact of toxic stress.”

Such stress, which is receiving ever-more attention in the healthcare and social-service communities, occurs, according to the Harvard Center for the Developing Child, in response to the strong, frequent, and/or prolonged activation of the body’s stress-response system without adequate protective relationships and other mediating factors (Li’s spiking heart rate when police appeared on the scene, for example). Stressors may include individual experiences of adversity, as well as family and community circumstances that cause a sense of serious threat or chaos.

Reducing such stress and minimizing its impact has become, in many ways, Senn-McNally’s life’s work. And a big part of it is compelling young doctors, through exercises like the poverty- simulation seminars, to understand how those social determinants of health directly impact the patients they see every day.

“These are things that are non-medical, but certainly impact people’s health and wellness — where they live, where they go to school, whether they have transportation, whether they have access to resources,” she explained. “Through their participation in the simulation seminars, residents and medical students get some empathy around when patients show up late, and they start to understand that health and wellness happens, really, outside the clinic and not only inside those walls. And they begin to understand the stress of living in poverty.”

If one listens to Li and other residents who have taken part in such simulations, Senn-McNally is succeeding in transforming this empathy, this understanding, into better care for this at-risk population.

Dr. James Li says the poverty-simulation seminar he took part in gave him greater appreciation of the challenges facing many of the patients he sees.

“The simulation and what I learned from it allows me to take things a step further,” said Li, a graduate of the medical school at Florida International University. “I know what the book says in terms of what these patients need. But now, I’m thinking more about how I can go outside the box to actually make it work for them.”

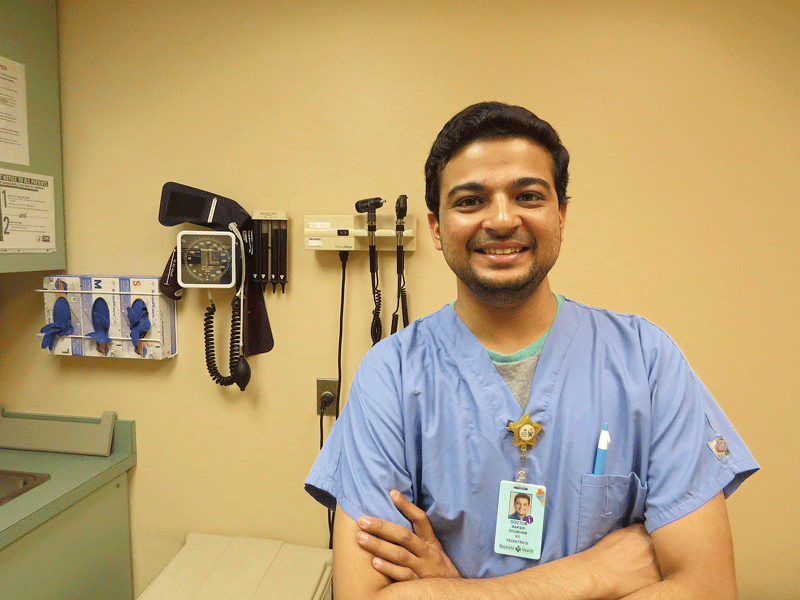

Dr. Shubham Bakshi, who has also taken part in a poverty-simulation seminar, agreed.

“The simulation has given me a different perspective on how to make sure individuals get the right amount of help, and that we match them up with the resources that are available in our community,” he told BusinessWest. “We take things for granted that we shouldn’t take for granted. That’s what this simulation has shown me, and it will make me a better doctor.”

Ready to Act

Bakshi, a native of India and graduate of Ohio State University and then Northeast Ohio Medical School, said he was obviously not experienced in what it’s like to be a 14-year-old girl, especially one in a family living in poverty.

But that was the role that the pediatric resident was assigned in his poverty-simulation seminar — “I didn’t volunteer” — and, like any good actor, he soon became immersed in his role, if you will. In this case, that meant coming to grips with all the sentiments, emotions, and, yes, toxic stress that such an individual would encounter as they are presented with a task, or scenario, as well as their assignment, which, as he put it, is to simply survive the environment they’d been placed in.

“The environment that I was given was that my dad had just left us, and everything fell to my mom, who was not educated and didn’t have enough skills to work in many jobs; everything fell on her to support us,” Bakshi recalled. “And being a 13- or 14-year-old, I was not able to get any jobs.

“It was eye-opening, because these are real experiences — these are real-life scenarios, as I later found out while practicing in Springfield,” he went on. “I knew that poverty was a challenging thing, especially with child care, but the simulation was very eye-opening; my mother was earning $30 a day, and our rent was $700 a month. It was really hard to make ends meet.”

Creating these eye-opening experiences and, more importantly, changing the way physicians think about how to properly care for those living in poverty is only the latest example of how Senn-McNally has spent much of her career working with and advocating for people at risk.

Indeed, her résumé includes stints with a host of community health and wellness organizations ranging from the New Beginnings Domestic Violence Shelter in Newark, Ohio, to the Franklin County Community Action Center for Self-Reliance, a homeless drop-in center in Greenfield.

Through those experiences and many others, including three years at Connecticut Children’s Hospital in Hartford working in its primary-care center, she brings a keen awareness of those aforementioned social determinants of health to work every day, and making others as aware is now a big part of her duties as a pediatrician and educator.

And in those capacities, she wears a good number of hats. She has her own practice, working at the clinic on High Street, which serves some of the poorest neighborhoods in Springfield.

And like many who work with children, she finds that work not only rewarding, but enjoyable.

“I love kids, and have moments every day where I say, ‘I’m so lucky to be able to spend time with kids and families all day long,’” she said. “A kid does something funny or silly, and we smile; I’m not sure that happens for people who are taking care of older folks.”

She also serves as Springfield’s school physician.

In that role, she works with the school nursing leadership as their healthcare consultant, and has worked with school officials on a number of initiatives, including substance-abuse screenings.

A pilot program involving seventh- and 10th-graders was launched last year, she said, adding that school nurses undertake what are known as SBIRT (screening, brief intervention, referral, and treatment) screenings designed to make the nurses resources in the ongoing battle to stem the tide of substance use.

“The nurses just have a conversation with the kids about substance use,” said Senn-McNally. “And one of the wonderful things about these conversations is that they are preventive; they’re an opportunity to talk with students about substances, hopefully before they’ve started using in the seventh grade, and emphasize the positive choices that kids are making if they haven’t starting using or if they’ve stopped, and see the school nurse as a resource.”

And she is also an educator, specifically associate program director for the pediatrics residency program at Baystate, another role with a host of rewards.

“I love working with residents and medical students,” she told BusinessWest, “because I really think we have a chance to shape how they are as physicians, what they value, and how they grow and treat patients.”

And the poverty-simulation seminars she oversees play a very big role in these efforts.

On a Role

Such simulations are taking place across the country, involving not only physicians and others in healthcare, but also elected officials, educators, business leaders, and other constituencies.

With each group, the goal is essentially the same — to create awareness of the myriad challenges facing those in poverty, and to see this awareness translate into positive change when it comes to how communities and individuals serve the poor and deliver services.

The simulations feature volunteers, perhaps 20 to 30 of them, who are residents of the community and either work with people in poverty or who have lived in or close to poverty, said Senn-McNally, adding that the ‘participants’ are medical residents or medical students who role play for an hour (four 15-minute ‘weeks’) living in poverty.

“They’re placed in families of varying types, maybe a single mom with several children, parents who may have lost their jobs, or an older single adult supporting themselves on disability, for example,” she explained. “And they have to complete a number of tasks over those four weeks; they have to pay their rent, they have to feed their families, and they have to keep the electricity on. And they really experience a small measure of what the families we take care of experience in their lives.”

After the simulation, there is a debriefing, she went on, adding that these sessions, where the participants, such as Li and Bakshi, discuss what they just experienced with the volunteers from the community, are quite compelling.

“The participants talk about how they felt during the simulation, and the community members have a chance to comment on what they saw, and whether the simulation was realistic, went far enough, or didn’t go far enough,” she explained. “And it’s such a powerful conversation, because the volunteers get to share their real-life experiences with our medical students and residents, who have typically grown up with more privilege than the people running the simulation.”

What happens after the seminars is obviously the most important part of this equation, though, said Senn-McNally, adding that the goal is to not only create an understanding of what it’s like to live in poverty, but better serve that population. And she believes the seminars are creating progress in this realm.

“The residents and medical students learn that people have to prioritize when they’re living in poverty,” she explained, “and that meeting their basic needs, food and shelter, may take precedence over their medical needs.

“They learn about why patients don’t always get an appointment when they’re supposed to — because they needed to take three buses or they didn’t have a car or they had to walk,” she went on. “And when they’re more empathetic, they’re able to be more understanding; they’re able to understand the importance of talking to patients about whether they have enough food, about their living situation, how school is going, and more. Doctors don’t typically ask about such things.”

Today, and in large part because of the poverty-simulation seminars, Li, Bakshi, and others are asking such questions, listening carefully to the answers, and using them to help improve their patients’ overall health and well-being.

With that, Li returned to that thought about outside-the-box thinking and going beyond what the book says.

Dr. Shubham Bakshi says his role as a teenage girl living in poverty certainly opened his eyes to the challenges facing that constituency.

To get his points across, he used the example of an extremely overweight patient.

“His BMI is in the 95th percentile, which means he’s overweight-slash-obese,” said Li. “You look at his diet history and you see that he’s eating at McDonald’s four times a week. It’s easy to say ‘you should stop that,’ but it’s harder to say that when you realize he’s eating at McDonald’s because it’s the cheapest way that they can get the calories they need to live and to function. I know I have to take it a step further than what’s obvious and telling him not to eat that food.”

Bakshi agreed, and said that before the seminar, he, like most others in his position, would make assumptions and take some things for granted, things he’s learned he shouldn’t do.

As an example, he cited a call he received from a woman living in a shelter concerned about a rash her child had developed.

“I said to her, ‘I’m a little concerned about that because you’re complaining of fever, nausea, vomiting, etc.; why don’t you go to the emergency room?’” he recalled. “Later, I realized she said she lived in a shelter and that it would be hard for her to arrange that transportation. Also, it was 10 at night.

“Now, in that same situation, I think my first question would be, ‘do you have reliable transportation?’” he went on. “Before, I just assumed they did; now, I have changed my perspective and the way I take such calls from these patients. I’ll say, ‘where do you live?’ or ‘who else lives with you?’ or ‘who is supporting you with taking care of the child?’ and ‘how are you making ends meet?’”

Part of the Solution

The gentleman who played the police officer in Li’s poverty-simulation seminar is a greeter at the High Street clinic. Li sees him almost every day.

His heart doesn’t race when he does. But it certainly did that day back during his residency orientation. That’s how realistic that exercise was in essentially bringing Li into a life of poverty and forcing him to somehow survive.

The toxic stress was very real. Also real are the changes in the ways that Li and others like him are looking at, talking with, and treating those who come into their care.

And Molly Senn-McNally has played a lead role in bringing about those changes.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]