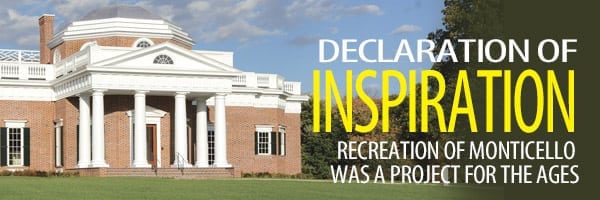

Declaration of Inspiration

Recreation of Monticello Was A Project for the Ages

Bill Laplante remembers the phone call like it was yesterday.That’s because it seemingly came out of nowhere, and also because it marked the unofficial start of easily the most intriguing — and also one of the more challenging — endeavors in his long career as a home builder, and what he would repeatedly call “the opportunity of a lifetime.”

On the other end of the line was S. Prestley Blake, the then-98-year-old co-founder of Friendly Ice Cream and admirer of both Jefferson and the Laplante company’s work — it built the home his daughter and son in law now reside in, and also the new residence for the president of Springfield College (erected a dozen years ago), for which Blake developed a deep appreciation regarding both its design and workmanship.

“He said ‘Bill … I’m thinking about building a replica of Monticello in Somers,’” said Laplante, president of the East Longmeadow-based firm launched by his father, Ray. “He said he wanted me to come over and assess the property, take a look at things, review the site plans … that’s how it all started.”

It all ended just a few months ago, with a black-tie party that was combination early 100th birthday bash and open house attended by more than 250 people at what would have to be called ‘Blake’s Monticello,’ although it’s highly unlikely that he’ll ever spend a night in it.

This Monticello, slightly smaller than the original, Thomas Jefferson’s home in Charlottesville, Va., is what Blake, reached by BusinessWest in Florida, called, alternately, a “gift to the community,” his “swan song,” and “something I’m doing for posterity, not profit.”

Indeed, he expects to certainly lose money on the home currently on the market with a sticker price of $6.5 million, roughly $1 million less than what it cost to buy the land, raze what was on it, and build the landmark. There have been a few inquiries, and those interested will have to eventually impress Blake, who has the final say on this sale and insists he’ll only sell to someone who has both the requisite financial wherewithal and the same commitment to the community that he does.

As for Laplante, his crews, and lead design consultant Jennifer Champigny (not to mention Prestley Blake and his wife Helen) the endeavor quickly became a labor of love, a project no one really wanted to see end, although everyone involved was firmly committed to getting things done before Blake became a centenarian last November. Overall, the huge undertaking was completed in an impressive 14 months, more than three decades less than it took Jefferson to complete the original.

“The whole project, from start to finish, was a lot of fun … everyone who worked on it, from day one, thoroughly enjoyed it,” said Laplante. “It truly was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

The building process, began in the spring of 2013, soon after Blake closed on the nine acres of land off Hall Hill Road, just a few hundred yards from the Massachusetts border, and the structures built on it (owned then by the estate of the late Big Y co-founder Gerry D’Amour and his wife Jeanne). It was preceded by a visit to the original Monticello by Laplante and his father.

They took hundreds of photographs, made volumes of notes, and purchased the book Monticello in Measured Drawings, which soon became invaluable.

Bill Laplante, standing in the foyer at the

Somers Monticello, called the project the “opportunity

of a lifetime.”

“I think this is the most prominent private house in the country,” Blake told BusinessWest in reference to his creation, noting that this assessment is based on aesthetics and the model that inspired it, not sheer size or features. “The White House is the most prominent house in the country, but that’s owned by the government. This is a private house I built on my own.”

For this issue and its focus on contruction, BusinessWest takes an in-depth look at why Blake’s Monticello came to be built and how. In the course of doing so, it became clear why those who view the house use the same word to describe it as those called upon to recount the building process: memorable

Landmark Decisions

They eventually dubbed it ‘Monticello Highway.’

That was the name given to the path that Blake had carved between the site of the Somers Monticello and his own home, just a few hundred yards away (the properties abut).

Blake would take that path on his small, four-wheel-drive motorized vehicle called a ‘Gator,’ said Laplante, adding that he was at the construction site by 7:30 a.m. almost every day he was in this region to observe, take photos, and offer both suggestions and commentary — mostly the latter, because he gave great latitude to the builders.

What the Blakes saw emerge on the gently rolling parcel is one of the few replicas of Monticello in this country — there’s a bank modeled after it in Monticello, Ind., and a chiropractor’s office in Paducah, Ky., for example — and certainly the most extensive and expensive.

The Monticello in Somers has a number of things the one in Charlottesville doesn’t, including:

• A three-car garage;

• A tiled patio atop the three-car garage, which was a very popular gathering spot during the party in October;

• An elevator;

• Laundry rooms on the first and second floors;

• A wine chiller;

• Wolf and Sub-Zero appliances;

• A pantry with floor-to-ceiling cabinets, a so-called library ladder to reach those heights, and leathered granite counter tops;

• Five full baths complete with walk-in showers, towel warmers, and other amenities;

• Coffee stations in most of the rooms and a second-floor kitchenette; and

• Geothermal heating and cooling.

It does, however, have many of the same exterior features, including the white columns, roof ballustrades, and signature dome at the front of the structure (or the back at the original Monticello; the back entrance was the main entrance in Jefferson’s time), and some interior elements as well, including a tea room, a lavish foyer (although the one in Somers has a double staircase), ornate hard-wood floors, and so-called great room.

Retelling the story of how it all came about, Laplante said Blake was never particularly fond of the large estate built by the D’Amours, and has always been enamored with Monticello, architecturally and otherwise, and conceived a project to replace one with the other and, in the process, build something memorable and lasting.As Blake was finalizing his purchase of the site, he was also engaging Laplante on the undertaking to come.

The trip to Charlottesville was educational and therefore quite helpful, said Laplante, adding that this was his first visit to the landmark.

“We met with the people giving the tours of Monticello, we toured the entire facility, and took a number of photographs, including many detailed photographs,” he explained. “We were focusing on the exterior of the building, because the original plan called for building a replica of Monticello, especially with regard to the exterior façade, but make it into a modernized single-family home on the inside — something that someone would be interested in purchasing and living in.”

Monticello in Measured Drawings became a valuable resource, he went on, adding that it was assembled by an architectural group that recreated scaled drawings of the original.

“It was very difficult, because there were areas that were 1:32 scale, because of the size of the house and obviously the size of the book,” Laplante explained. “We were dealing with very, very small scale, but it was very helpful having that, as well as the photos we took of the original and the tours we took.”

Glory Details

Beyond the basic mission of reproducing the original Monticello’s exterior, the Blakes’ only real instructions to the builders were simple, said Laplante, adding that he was told not to spare any expense, to build a replica as exacting as possible, and, inside “to make every room spectacular.”

And by all accounts, he and his crews followed those instructions to the letter.

Attention to detail can be seen in many aspects of the recreation work, including the brick used. Bricks in the original were hand-made made on-site in Virginia, said Laplante, adding that those used in Somers were also hand-made and cast to look like what was used in the early 19th century.

The decision was made early on to place the dome at the front of the house, the side facing Hall Hill Road, said Laplante, adding that the ‘front’ façade of the replica is, by his estimation, 98% accurate to scale.

One of the main differences between the two Monticellos is that the one in Virginia has an open porch, complete with arched-brick openings, on the left side, while the one in Somers has an enclosed hearth room, located just off the kitchen, in that location.

Also, Jefferson’s Monticello had a room inside the dome, while the one in Somers does not, and the second-floor windows in the replica are larger than those in the original to meet modern building codes.

“Working around the windows was perhaps the biggest challenge in designing this, because we were designing an interior around an exterior that was built 200 years ago,” he said, adding that both the original and replica (at least from the ‘front’ view) are two-story homes that don’t look like two-story homes.

The kitchen in the Somers Monticello is certainly different than the one in Thomas Jefferson’s original in Charlottesville, Va.

“From the beginning, the Blakes said, ‘we want every room we walk into to be spectacular,’” said Laplante. “But they didn’t micro-manage the design and the details; they let us come up with what we thought should be done.”

Some of the details were taken from the original, he went on, citing such things as floor patterns (although slightly different wood species were used), but the interior obviously bears little resemblance to the one in Charlottesville.

The kitchen in Jefferson’s Monticello was a simple facility in the basement. The kitchen in Somers is massive, with the most modern appliances and quartz countertops. The Monticello in Virginia had five outdoor privvys; the one in Somers has nine baths, many of then featuring Carrara marble.

The biggest difference between the two landmarks, however, is the ‘green’ nature of the replica. Jefferson heated with wood. The Somers home features geothermal heating and cooling equipment (which Laplante said is becoming increasingly popular due to attractive tax credits). It also has LED lighting, energy-efficient windows and doors, and icynene spray foam insulation. Meanwhile, raw materials from the site, including oak and cedar trees and red stone harvested from the parcel were used in the construction.

Overall, the buildings are worlds apart in terms of building materials and processes and creature comforts, but they look remarkably similar in large, framed photographs hanging side by side in the wood-paneled garage.

History in the Remaking

In addition to the party in October, the Blakes had a small gathering in the Somers landmark just before the holidays.

For the event, dubbed ‘Christmas at Monticello,’ the Blakes actually borrowed a few pieces of furniture and had some tables placed in the great room, said Laplante, who was among those invited.

The scene was a little strange, he recalled, but understandable because while the Blakes built the home, technically, it’s not theirs.

Soon, if the right buyer and right price come together, it will belong to someone. But it many respects, it will always belong to the community, said Blake, adding that, like the original, it was built to last and built to inspire.

And it is already doing just that.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]