Friends of the Holyoke Merry-Go-Round

Seizing the Brass Ring

Friends of the Holyoke Merry-Go-Round Are Preserving a Treasure

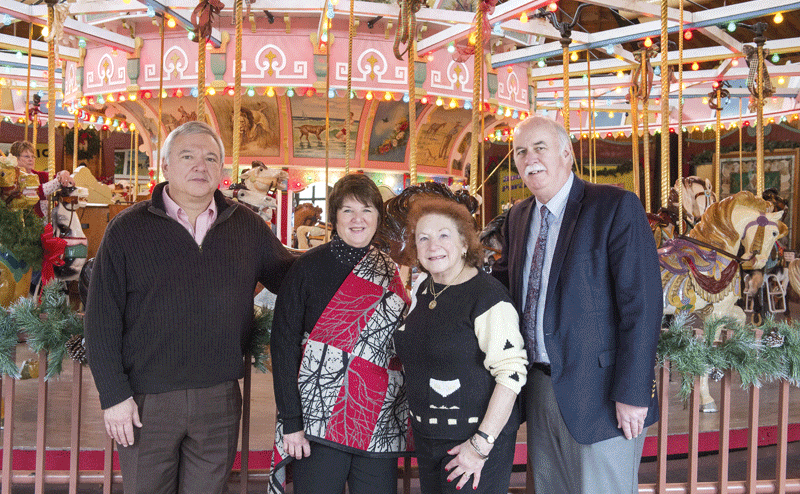

Some of the many passionate Friends of the Holyoke Merry-Go-Round: from left, Jim Jackowski, Barbara Griffin, Angela Wright, and Joe McGiverin.

The giant scrapbooks, their newspaper clippings turning yellow and their heavy leather covers fraying and kept on with shoelaces, are getting on in years — as are the people who created them.

But the truly inspiring story they tell never gets old.

It’s about how one of the poorest communities in the Commonwealth, then and now, came together, in every sense of that phrase and against very long odds, to raise nearly $2 million during a stubborn recession to keep the historic Mountain Park merry-go-round in Holyoke.

Carefully chronicled in those scrapbooks, this story relates tireless fund-raising efforts — from generous donations given by large corporate players to a fishing derby with a $10 entrance fee that went to the cause; from phone-a-thons and mailed solicitations featuring carefully crafted pleas for support to sales of everything from sweatshirts to Christmas-tree ornaments out of a donated kiosk at the Holyoke Mall.

It also captures work to find, finance, build, staff, open, and operate a home for the merry-go-round in Holyoke’s Heritage State Park in late 1993, an important chapter in this tale and one with many twists and turns.

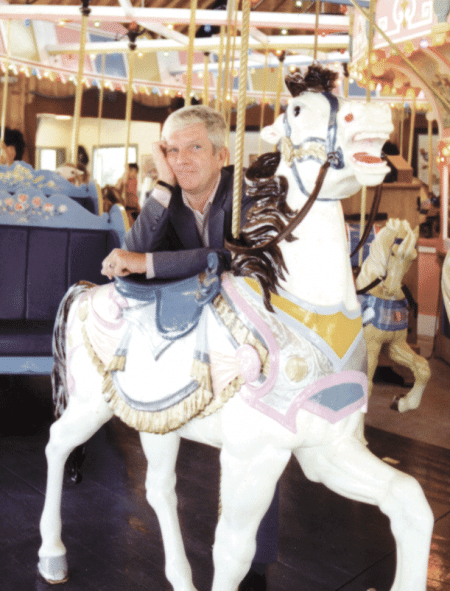

John Hickey, a.k.a. “Mr. Holyoke,” rallied the city to seize a “glittering brass ring.”

And those scrapbooks poignantly reflect, through photos, news stories, and his own commentary in the daily Holyoke Transcript Telegram, the passion, commitment, and drive of one John Hickey, known to most as “Mr. Holyoke,” who rallied the city and unified it behind what was, at the time, a most unlikely cause.

“He was determined; he felt like this was an important piece of Holyoke’s history and that there needed to be a way to save it,” Angela Wright, long-time volunteer director of the merry-go-round and one of the leaders of the effort to keep it in the Paper City, said of Hickey, then head of the Holyoke Water Power Co., who passed away in 2008. “He was like a pied piper … he went to every meeting, every organization, every business he could to stress the importance of this. And he got a city behind him.”

Indeed, Hickey ended one of his op-ed contributions (a piece that has become part of Holyoke lore) with a question that doubled as a rallying cry.

“There’s a glittering brass ring out there,” he wrote in reference to the carousel. “Will the people of Holyoke extend themselves to capture it?”

Indeed, they would, as the pages of those scrapbooks make clear, and more than 1.2 million people have gone for a ride.

But the last entry in those volumes is from Dec. 1, 1994 — a short story about upcoming Christmas happenings at the carousel — and, therefore, they don’t tell the whole story.

Indeed, while the efforts to buy the carousel and then begin its next life in downtown Holyoke could be described as ‘heroic’ and ‘monumental,’ what has transpired over the past 23 years or so and continues today is worthy of equal praise, said Jim Jackowski, business liaison for Holyoke Gas & Electric and long-time president of Friends of the Holyoke Merry-Go-Round Inc., the organization created to not only buy the treasure, but manage it and preserve it for future generations.

The second part of the equation isn’t captured in the scrapbooks because, for the most part, that hard work doesn’t generate headlines, he said. But the challenges to operating and properly maintaining the carousel — everything from spiraling insurance costs to non-stop maintenance to restoration work on the ornate horses — are many and formidable.

But the same passion that went into raising the money to buy PTC 80 (the 80th carousel built by the Philadelphia Toboggan Co.) goes into the work to keep the ride spinning today — and tomorrow, said Jackowski.

“It’s been a labor of love — it was then, when we were raising the money to buy it, and it still is today,” he explained.

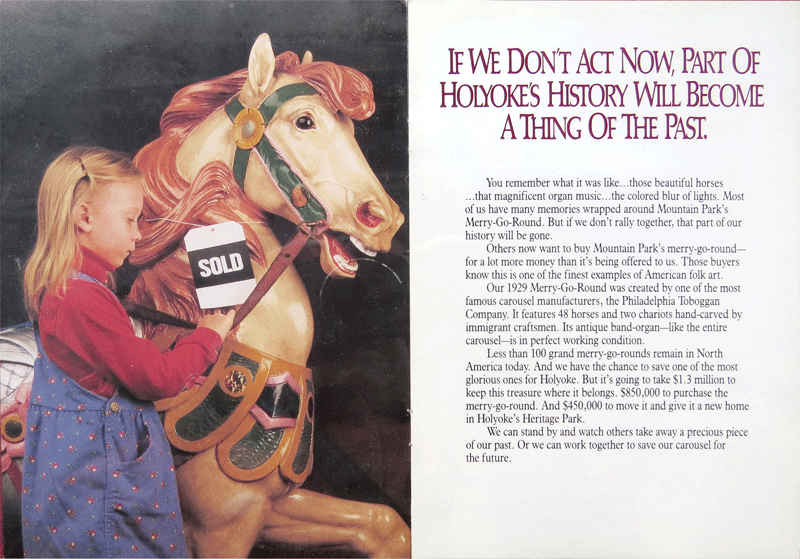

One of the many ads designed to emphasize what Holyoke would lose if the merry-go-round went to another buyer.

And that sentiment is perhaps best summed up with words from the Transcript Telegram, which played its own sizable role in the efforts to save the carousel.

Its presses fell silent in January 1993 as the paper succumbed to disastrous losses in the wake of the early-’90s recession. But it still has a voice on this subject (and this Difference Makers award) thanks to an editorial published just a few weeks before the paper closed.

The occasion was a decision of the state Department of Environmental Management to award $300,000 for the construction of a building in Holyoke’s Heritage State Park for the carousel, providing it with a home and, essentially, sealing the deal.

“If one project in recent history had to be chosen to represent the best Holyoke has to offer in community spirit, from the youngest child to the most senior resident,” the paper roared, “then the campaign to save the Holyoke Merry-Go-Round is it.”

More than 24 years later, those words still ring true.

Mane Attraction

Among the many individuals, groups, and businesses that donated in-kind services to the cause of saving the merry-go-round was the Hartford-based marketing and advertising firm Adams & Knight Communication.

The firm had a number of specific assignments — from designing promotional brochures destined for potential donors to crafting copy for print ads that ran in the Transcript Telegram and elsewhere. But one of its very specific tasks, apparently, was finding children with the ability to look sad. Really, really sad.

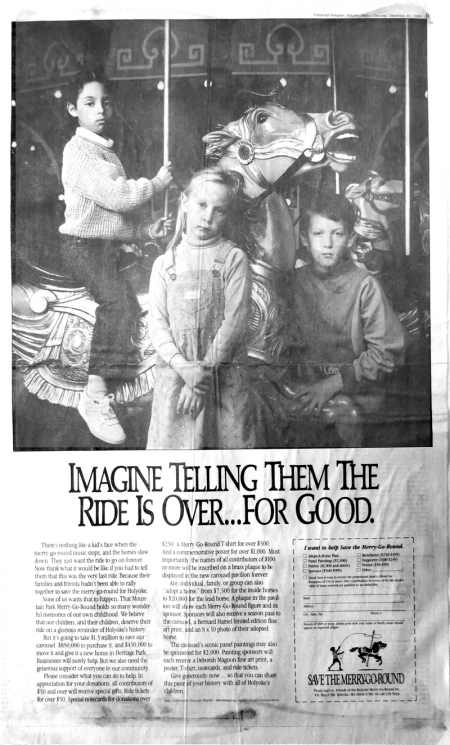

Children recruited for ads used in the merry-go-round campaign had plenty of practice looking sad.

For example, there’s one young girl displaying that talent in an ad (that appeared in multiple outlets) in which she stands next to one of the carousel’s horses wearing a sign around its neck reading ‘sold.’ She’s holding on to its reins as if she doesn’t want to let go, clear symbolism of the city’s attitude at the time.

She makes another appearance, along with two other children, in an ad that features a broad view of the carousel with the headline “Imagine Telling Them That the Ride Is Over … for Good.”

And there’s a despondent yet still-hopeful young boy featured in yet another full-page ad. He’s holding out his piggy bank, as if to offer whatever’s in it. The headline reads, “Why He’s Putting All His Money on a Horse.”

But it wasn’t just young people enlisted to send this message. Indeed, several teenagers (from the ’50s, presumably, based on their attire) are featured in still another ad with the headline, “If You Care About Holyoke’s Future, Put Money Down on Her Past.”

In essence, this is what the campaign started in 1988 was all about, said those we spoke with, adding that it wasn’t just about keeping PTC 80 from being sold off as a unit or piece by piece and shipped overseas.

It was also about people investing in the city’s future, said Jackowski, meaning both the generations to come and the city itself, which needed a boost to spark its sagging fortunes and deteriorating downtown.

These sentiments are reflected in comments attributed to then-Mayor Marty Dunn (another of this story’s many heroes) in one of the many promotional pieces created to solicit support.

“This is not a toy,” said the mayor. “It is a folk-art masterpiece and a powerful attraction for our downtown.”

The merry-go-round has, by most accounts, become that spark, that attraction, thanks to the campaign to save it and, more specifically, that group that came to be known as the Friends of the Holyoke Merry-Go-Round.

It was created and led by Hickey, who first approached John Collins, owner of Mountain Park, who closed that attraction in 1987, with a proposal to allow the city of Holyoke to buy the carousel and thereby keep it ‘home.’

By most accounts, this wasn’t exactly a hard sell. Indeed, while Collins reportedly had some handsome offers for the merry-go-round on the table, including a rumored $2 million, he was supportive of the efforts to keep it in the city, and thus he set the bar, or price tag, low — $875,000.

While there was considerable support for the merry-go-round, in Holyoke and beyond, all those involved knew that raising that kind of money, at that time and in that community, would be very difficult. And, as we’ll see, the community would soon see that number rise considerably.

It’s been a labor of love — it was then, when we were raising the money to buy it, and it still is today.”

And this is where our story — the one told through the clips in those scrapbooks — really begins.

However, those we spoke with say it really starts with John Hickey.

Indeed, he was the one, said Wright, who convinced Holyokers, then facing a mountain of other, seemingly more pressing issues, from rampant unemployment to soaring poverty to a declining downtown, that the merry-go-round was still a treasure worth saving.

“In the beginning, people were saying, ‘are you kidding — a merry-go-round?’” Wright said while trying to capture the mood at the time. “There were so many other problems, from homelessness to the schools to downtown. People said, ‘how can you be thinking about raising money for a merry-go-round?’

“John would say to them, ‘you don’t understand — beauty is for your soul; there needs to be art, music, and beauty in this world, for everyone,’” she went on. “He would say, ‘this is as important as food’; he would make that comparison and stress the importance of art in one’s life.”

Round Numbers

To effectively reach the people of Holyoke, and beyond, Hickey would make early and frequent use of the Transcript Telegram’s op-ed page. Some of his early entreaties capture his passion for the project and his belief that it was an important part of the city’s history, identity, and psyche.

“A city needs more practical things, like sewage-treatment plants, snow plows, water filtration, better roads, and good school buildings,” he wrote on March 5, 1988, just as the campaign was being conceptualized. “But it also needs objects that nourish its spiritual life. A beautiful and historic, million-dollar merry-go-round may be a bit of mirthful indulgence, but it will give us, for generations, a special kind of happiness and pride.

“It is sad that we are losing our historic amusement park,” he would go on a few paragraphs later, “but it would be tragic if we stood by, doing nothing, and letting its centerpiece, the merry-go-round, become the object of pride and fame in some other distant city.”

Merry-go-round employee Kathie McDonough, left, staffs the concession stand with long-time volunteer Maureen Costello.

Beyond passionate rhetoric, though, Hickey understood that this campaign needed a solid foundation on which to build, and to erect one, he turned to the many banks and other prominent corporate citizens at that time, said Wright.

“He pulled together all the CEOs and banking leaders and put them in a room,” she recalled, adding that, prior to this now-historic gathering, he took them to Mountain Park for a ceremonial and sentimental look at the carousel. “He talked for an hour about the value of this merry-go-round, not only to families and kids, but for history, nostalgia, as an anchor to downtown … he went through the whole thing.

“And he said, ‘unless you people commit a big number — and I mean a big number — then we can’t do it,’” she went on. “And by then, he had them practically in tears.”

Before the meeting convened, a big number, $300,000, had indeed been pledged, she went on, adding that, as for the rest … well, there were a variety of imaginative, and effective, strategies put to use, as told by the stories, ads, and posters clipped into the scrapbooks.

Famously, schoolchildren in the city raised $32,000 in two weeks from selling cookies and candy door-to-door, and for that work, a plaque was placed next the armored lead horse in their honor (such plaques were placed under each horse to commemorate donors.)

There was that fishing derby at the Jones Ferry Marina (“now is the time not to flounder,” wrote the creative scribe at the Chicopee Herald); Holyoke Community College raffled off a free semester of study to aid the cause; musicians performed at a benefit concert; the city’s aldermen launched a charity ball, with the merry-go-round as the first recipient of proceeds; commemorative stamped envelopes were issued with the likeness of the lead horse on them (the price was 25 cents, which will tell you how much water has passed under the bridge).

Also, schoolchildren sold Christmas ornaments; artists sold limited lithographs of the carousel; there were car washes, phone-a-thons, a 10th-anniversary party at the mall, with the carousel as the beneficiary. And at the Merry-Go-Round Gift Store (the storefront donated by the mall) and other locations, supporters could buy hats, ornaments, tote bags, sweatshirts, a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle, mugs, notecards, and several different posters with carousel imagery. The headline on the ad promoting it all in the Dec. 9 issue of the Transcript read, “Now You Can Finally Get a Pony for Christmas.”

Turn for the Better

As noted, the brass ring Hickey mentioned became the unofficial prize, if you will, and the phrase appeared repeatedly in ads and news stories throughout the campaign.

But even as the original goal of more than $1 million came closer to reality, the bar moved, and in a big way, said Wright, noting that, from the beginning, organizers knew they would have to build a home for the carousel.

They had a pledge from the state of $300,000 to build that home, she said, but as time went on, huge doubts emerged about whether the state could uphold its end of the bargain given the enormous financial pressure it was under, and whether that amount would be enough.

As things turned out, the state did keep its promise, but that figure wasn’t nearly enough (bids for the structure came in at twice that total).

Photography by Leah Martin

But funds to cover the difference were raised with significant help from Warren Rhoades, then-president of PeoplesBank, she said, adding that this triumph would be one of the countless enduring stories from the campaign to save the carousel and then operate it, many of which simply didn’t generate headlines, but certainly contributed to that phrase ‘labor of love.’

As she recounted some of them, Wright said she didn’t really know where to start.

She eventually settled on Jim Curran, a contractor and owner of the Wherehouse banquet and meeting facility in downtown Holyoke, who not only stored a large amount of the carousel’s thousands of components — most of the horses were kept in a locked railroad car, and Hickey even kept some in his living room — but also took the carousel apart and played a huge role in the very complex, time-consuming effort to put it all back together.

“It was like a giant puzzle,” she explained. “There were boxes and boxes of nuts and bolts; it was mind-boggling to me.”

Wright also mentioned her husband, Joe (the couple have a long history of philanthropy in their native Holyoke), who assisted with piecing the carousel together and maintaining it; Tim Murphy, the architect who designed the carousel’s new home in Heritage State Park; Will Girard, a neighbor of the Wrights who has assisted with seemingly endless repairs and maintenance; the Gaul family, which donated the huge concession stand now at the carousel, replacing what amounted to a card table that was there at the start; Craig Lemieux, who volunteered the time and labor that went into building the ramp to make the carousel handicap-accessible; and the Steiger family for gifting to the carousel the Tiffany window that graced its downtown Holyoke store.

And on she went, noting that there were, and still are, volunteer angels whose names she never knew and faces she never saw.

“When we first opened, we didn’t have any money; we had no debt, but we also had no money,” she said. “And people just did things. Like cleaning the windows — people would appear … in the dark of night; I don’t know, I never saw them.”

The Ride Stuff

In many respects, this community spirit and volunteerism continues today, said those we spoke with, adding that the task of keeping the carousel open and operating is daunting, and a small army of volunteers is still needed.

Speaking in broad terms, Jackowski said operating a merry-go-round is a tough business these days — so tough that many have actually closed in recent years — and this one is no exception.

He cited everything from the myriad competitors for the time and attention of children and families to the rising cost of doing business (and generally flat revenues), to changes in Holyoke itself.

“It’s like any other business — there are fixed expenses and just stuff that you have to do,” he said, adding that there is quite a lot of ‘stuff’ with this ride that is now nearly 90 years old. “It’s a piece of machinery that requires maintenance and upkeep and hardware. And the community has changed in the 20-plus years since we opened; we had a bigger presence of retail and shopping when we first opened, and a lot of what was downtown and drew people to the downtown is unfortunately not there anymore.”

As one example, he cited Celebrate Holyoke, the annual summer festival that drew tens of thousands of people to Holyoke during its four-day run, which was discontinued several years ago.

“That used to be a huge weekend for us — we would get 20,000 riders in four days,” he explained. “Once that went away, it was hard to make up those riders; even at $1 per head, that was $20,000.”

And that challenge goes a long way toward explaining why a ride now costs $2, which is still a great bargain and one of the lowest prices to be found for a merry-go-round.

But, as with the vast majority of museums and other types of attractions, admission doesn’t cover annual expenses, said Joe McGiverin, another long-time member of the Friends of the Holyoke Merry-Go-Round board, noting that labor (there are seven staff members) and, especially, insurance top the list of rising costs.

Thus, other sources of income must be developed and nutured.

Birthday parties, private functions, and a handful of weddings each year have long been one such source, said Barbara Griffin, another long-time board member and former staff member at the Log Cabin, who, with Jackowski and others, would handle the logistics of such events.

“That’s just one example of how of this is truly a working board — we don’t just go to meetings,” she explained, adding that, while the staff manages the carousel day-to-day and is largely responsible for that perfect safety rating, the attraction is dependent on volunteers today as much as it was when the money to buy the attraction was being raised.

And many of these volunteers have their own specific assignments, said Wright, who offered one of many examples.

“Joe is the security person — if the alarm goes off in the middle of the night, it’s his responsibility to go in there and see what’s going on,” she said. “Everyone on the board has a job, in one way or another.”

But overall, the volunteers are generalists, said McGiverin, and help with everything from keeping the grounds clean to staging the semi-annual Kentucky Derby-themed fund-raiser, called Derby Dazzle, at the site.

But there is another source of help at the carousel that speaks volumes about its hold on people — and its special place in Holyoke.

These would be the young people — and there are more than a few of them — who would like to ride but don’t have $2, said Griffin, adding that staff members will often let them take a spin in exchange for pushing a broom for a few minutes.

“If they want to sweep the floor or pick something up, we’d be more than happy to give them a little something in return,” she said, noting that, in the larger scheme of things, the carousel is what has been given to all of Holyoke, and the region as a whole, in return for the generosity that kept it here.

Wright agreed. “These kids … they know what we have, and you can’t let a kid walk by and just look in the window all day. You need to let them ride.”

That’s the kind of community spirit John Hickey was talking about all those years ago.

Words That Ring True

In March 1988, not even Hickey could have known what an attraction, and an institution, the merry-go-round would become.

Then again, maybe he did know. Or maybe … there’s no maybe about it.

What was it he wrote? “A beautiful and historic merry-go-round may be a bit of mirthful indulgence, but it will give us, for generations, a special kind of happiness and pride.”

Sounds quite prescient, as does that comment from the Transcript Telegram. Indeed, this was, and still is, the best Holyoke has to offer in community spirit, from the youngest child to the most senior resident.

And that’s why, nearly 30 years after this saga began, three decades after Hickey implored a city to reach for that “glittering brass ring,” the story about how it all happened never gets old.

And that’s also why the many Friends of the Holyoke Merry-Go-Round — those who have passed and those who still keep the city’s happiness machine turning — are true Difference Makers.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]