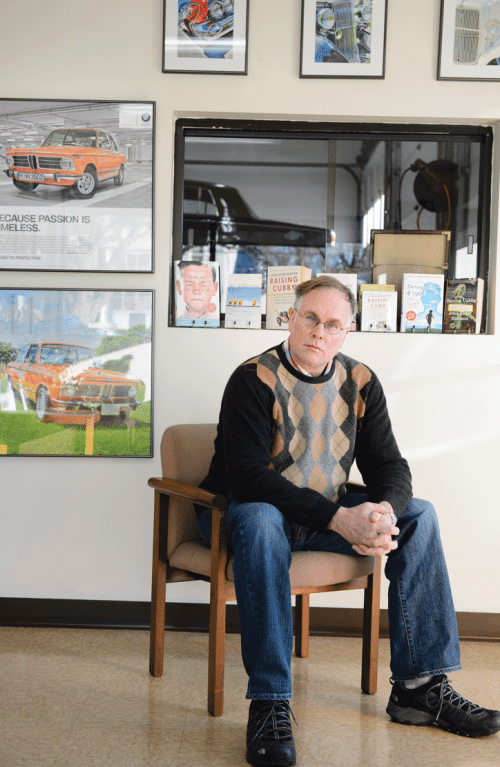

John Robison, President of J.E. Robison Service

His Efforts on Behalf of the Autistic Are a Global Phenomenon

John Robison, President of J.E. Robison Service

Leah Martin Photography

On the sill of the window in the front office at JE Robison Service, the one that offers a view into a long row of service bays that hosted Jaguars and Land Rovers, sits a display of the three books written by the company’s founder, John Robison, about Asperger’s syndrome and his life with that condition.

In chronological order, these would be Look Me in the Eye, which archives his life growing up; Be Different, which offers practical advice for Aspergians; and Raising Cubby, a memoir of his unconventional relationship with his son, who was also born with Asperger’s.

Near the middle of the display is a book with the title Wychowujemy Misiaka, which, says Robison, is the Hungarian version of Raising Cubby, only he doesn’t know if that’s a direct translation of those two words; a book will often take another title when published in a foreign country. For example, the Dutch version of Look Me in the Eye is titled I Always Liked Trains Better.

Meanwhile, there’s another book written in Russian; Robison thinks it’s Look Me in the Eye, but he admits he’s not sure and knows only that it’s one of his.

While the display creates some questions and confusion, it makes it abundantly clear that Robison’s efforts to raise awareness of disorders in what’s known as the autism spectrum, and advocate for the estimated 5 million people living with such conditions, are now a truly global phenomenon.

It’s an initiative with many moving parts — from the books to his numerous speaking engagements around the country; from a program at his foreign-car sales and service shop to train people with autism to be auto mechanics, to his participation on a number of panels created to help define the autism spectrum and improve quality of life for those who populate it.

John Robison says awareness that his differences stemmed from Asperger’s was empowering and liberating.

Leah Martin Photography

Indeed, Robison now represents the tip of the spear in a movement, for lack of a better term, that he and others are calling ‘neurodiversity,’ or neurological diversity, and all that this phrase connotes.

“This is the idea that neurological diversity is an essential part of humanity, just as racial, cultural, religious, or sexual diversity are,” Robison explained as he sat on a couch in that front office. “Those are all accepted things, and now we recognize that conditions like autism have always been with us, and we recognize that some autistic people are profoundly disabled — and indeed I’m disabled in many ways. But I’m also gifted in many ways, and that’s what people need to understand; autistic people have unique contributions to make to the world because of their difference, and the world needs that.”

While speaking on this subject, Robison also drives home the point that individuals within the spectrum — like those protected classes he mentioned — have a right, like those other groups, to be free from profiling and discrimination. And, at present, they are not.

As just one example, he cited one of the many mass-shooting episodes that have become commonplace in this country.

“The big thing about autism is how we’re treated related to other groups,” he explained. “I recall reading in the newspaper about how a bunch of people were murdered, and it said that the killer was on the autism spectrum.

“That’s a familiar headline for people, stuff like that,” he went on. “Can you imagine what would happen if someone went on the nightly news and said ‘seven people were murdered at a shopping center in Hartford today, and the killer was a Jew’? That guy would lose his job tomorrow. And yet someone can go on the news and say ‘seven people were killed in a theater, and the killer had autism.’

“Autism is no more predictive of mass murder than being Jewish,” he continued, adding that there is much work to do simply to make this fact known and fully understood, let alone prompt society to embrace neurodiversity, or the concept that society should accept people whose brains function in many different ways.

For doing that hard work, in many different ways, Robison can add the title Difference Maker to the several he already has.

Mind over Matter

There will soon be a fourth book competing for space on that shelf in Robison’s office.

It’s called Switched On, and its subject matter represents a radical departure from his previous works. This tome, finished several months ago, chronicles Robison’s participation in experiments at Harvard Medical School and Boston’s Beth Israel Hospital involving transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). The treatment is aimed at changing emotional intelligence in humans by firing pulses of high-powered magnetic energy into the brain to “help it re-wire itself,” said the author.

Those experiments, conducted from 2008 to 2010, yielded a mixed bag of results, said Robison, who explained, in some detail, what he meant by that.

“I think it succeeded beyond their wildest hopes in some ways,” he said of the regimen. “But as much as it turned on abilities in me, that came at a cost. It cost me relationships, and it made me more up and down, where before, I’d been on kind of an even keel all along.

“Suddenly, I felt suffocated by my wife’s long-time depression, I felt like I was drowning, and then ultimately I wasn’t able to stay married anymore,” he went on. “And before, I’d been oblivious to what people thought and said when they came in here for service; suddenly I began to see that some people were contemptuous of me and the business, and I didn’t like that. So I dismissed a good number of people I didn’t want to do work for anymore.”

All things considered, he describes what’s happened as a good tradeoff; he says he’s more knowledgeable and has greater ability to engage people. He was going to say more, but essentially decided that, if people want to know more, they could, and should, read the book, which will be out in March.

While Robison has devoted much of the past few years to this latest tome, he’s devoted much of his adult life to many types of work involving the autism spectrum.

That work started roughly the day he found out he was part of that population, he went on, adding that he didn’t know he belonged until a self-diagnosis, if one could call it that, several years ago that was spurred by one of his foreign-car customers.

Before detailing that episode, though, we need to back up a little and explain how Robison arrived there, because doing so helps explain his passion for what you might call his ‘other work.’

John Robison says much of his current work involves the emerging concept of neurodiversity.

His career track then took a sharp turn, and he ventured into the corporate world, first as a staff engineer at Milton Bradley in the late ’70s, and later as chief of the power-systems division for a military laser company. But while he had the technical know-how to succeed in those environments, he was missing the requisite social, interactive skills, including the simple yet important ability to look people in the eye.

“I didn’t fit in at large corporations,” he explained. “I didn’t say the right things, I got into trouble, I would say inappropriate things, I was rude. But, at the same time, I was a good engineer; I look at the stuff that I designed in rock ‘n’ roll and the toy industry with Milton, and I think my engineering work speaks for itself, even today.

“But I had significant social problems, and therefore I felt that I was a failure in electronics because of those things and because I couldn’t read other people,” he went on. “So I decided that, if I was failing at electronics, I would start a business where I wouldn’t be subject to being just dismissed; that’s what made me turn to fixing cars.”

And, eventually, selling them, restoring them, and connecting people with them. Indeed, his venture deals in high-end foreign makes and hard-to-find vehicles. He started working out of his home in South Hadley, later moved into space on Berkshire Avenue in Springfield, and now has what amounts to a complex on Page Boulevard.

The business grew to the point where he hired mechanics to handle the cars, and his work shifted toward operations, ordering parts, and dealing with customers. One of them, a regular, was a therapist, and during one discussion with him, the subject turned to Asperger’s. The therapist eventually gave Robison a book on the subject, one of many he would soon devour.

It was that reading that opened his eyes and eventually brought him to what can only be considered a global stage when it comes to advocacy for those on the autism spectrum.

A New Chapter

“It was a remarkable thing,” he recalled of the events that led him to understand why he was the way he was, even though a formal medical diagnosis would come later. “I learned things like autistic people have difficulty looking other people in the eye; it makes us uncomfortable. So, all my life, people had said things like, ‘look at me when I talk to you.’ I would look up and then quickly down, and I had no idea that other people were different in that regard.

“I felt all my life I was complying with what other people said, and yet they continued to be after me about it,” he went on. “It was only after reading that book that I understood how certain things that I did, like that, were different from what other people expected, and it’s because I was neurologically different. No matter how smart you are, you can’t possibly just figure that someone else sees the world differently than you do. So that book was life-changing.”

And as he talked about the process of discovering the cause of his “own differences,” as he called them, Robison used the words ‘empowering’ and ‘liberating’ to describe the phenomenon.

And as he talked about the process of discovering the cause of his “own differences,” as he called them, Robison used the words ‘empowering’ and ‘liberating’ to describe the phenomenon.

“If you’ve been told that you’re lazy, stupid, retarded, defective, or no good, for you to learn that you are touched by a form of autism, that’s … an explanation, and that’s really good,” he said, adding that, with this explanation, he would learn the ways autistic people (including those with Asperger’s) were different, and “teach myself to behave more like people expected.”

This was a transformative change, he went on, adding that he became more accepted in the community and forged real friendships, and this helped inspire his gradual development as an advocate, work that could be summed up as efforts to provide others with those same feelings of empowerment and liberation.

He said ‘gradual’ for a reason, because this work has certainly evolved over the years.

It began with speaking engagements to groups of young people at venues like Brightside for Families & Children and youth-detention facilities. The talks focused on autism, but also on Robison’s childhood, one marked by various forms of abuse.

“I realized that I could be speaking to young people about having a good life despite having that in your background, too,” he explained, adding that eventually he sought to reach a broader audience.

That led to Look Me in the Eye, an eventual bestseller published in 2006, and later his other works, all of which are now sold around the world. He believes that, worldwide, sales of the three books have topped 1 million copies.

But the books and the speaking engagements are only a few manifestations of Robison’s advocacy for people on the spectrum.

There is also the training school he’s created at his business for young people with autism. Conducted in partnership with the Northeast Center for Youth and Families, the initiative has transformed three bays at the Page Boulevard facility into what amounts to an instructional classroom for young people with learning challenges.

It was created with the goal of steering participants toward good-paying jobs in the auto-repair sector, and reflects Robison’s broader mission of transforming how people with differences should be valued and treated by society, and seen as productive contributors to society.

Other forms of service — and they often represent opportunities and appointments created through the exposure generated by his books — include participation on several boards and commissions involved with autism treatment and policy.

Four years ago, Robison was asked by then-Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius to serve on the committee that produces the strategic plan for autism for the U.S. government; that appointment has since been renewed by current HHS Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell. He also serves on a panel that evaluates autism research for the U.S. Department of Defense as well as the steering committee for the World Health Organization developing ICF (International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health) core sets for autism-spectrum disorder.

He also served a stint on a review board with the National Institutes of Health, tasked with determining how economic-stimulus money appropriated in 2008 should be spent on autism research.

While doing all that, he also teaches a class in neurodiversity at the College of William & Mary, one of the first programs of its kind in the country.

Add all that up, and Robison has a lot of frequent-flyer miles. More importantly, he has an ever-more powerful voice — one he’s certainly not afraid to use — when it comes to the rights of all those within the autism spectrum, how those rights are not being recognized or honored, and how all that has to stop somehow.

It all starts with recognition of those rights, he said, adding quickly that discrimination against those in the autism spectrum is more difficult to recognize because most people don’t see it as discrimination.

As one example, he cited educational testing, a realm where discrimination against some classes has been identified — because of which questions are asked and how — and, in many cases, addressed. Not so when it comes to those with autism.

“You could administer a math or reading test to someone like me, and because I can’t do math problems in the conventional way, I would fail that test,” he explained. “Yet, I could solve complex problems in math in real life, like doing wave-form mathematics in the creation of sound effects when I worked in electronics.

“If you were to test a person like me in a culturally appropriate way, I’d be a bright guy,” he went on. “But if you tested me the way Amherst High School tested me, I was a failure, and there are a lot of autistic people who are like me today. That testing sets us up for future failure, and it’s a form of discrimination.”

When asked if, how, and when various forms of discrimination, such as those headlines involving mass shootings, might become a thing of the past, Robison said this constitutes a difficult task, because so many don’t even recognize it as discrimination.

Progress will only come if adults within the spectrum take full ownership of their condition. And, by doing so, they would also stand up for their rights, as he does.

“We need adults with autism to own it and to say, “I’m autistic, and I’m going to fight for my equality,” he explained, adding that is what the memnbers of various ethinic, racial, and religious groups have done throughout history.

“Autistic people need to do the same thing,” he went on. “They need to say, ‘I’m an autistic adult, and I’m here to say that we’re no killers, we’re not this, and we’re not that; we’re parts of your community everywhere.’”

Summing up what he’s been doing since his customer gave him that book all those years ago, he would say it comes down to getting other people on the spectrum to assume that ownership.

The Last Word

As he talked with BusinessWest, Robison had to stop at one point to take a call concerning flight options for an upcoming speaking engagement in Florida.

It’s fair to say he’s mastered the art and science of booking flights, finding deals, and filling a schedule in a manner that allows him to do all he needs to do.

And that’s only one example — the books on that shelf, as mentioned earlier, are another — of how his work is now truly global in scope.

He said that book he read long ago opened his eyes, empowered him, and liberated him. Helping others achieve all that and more has become a different kind of life’s work.

And another way to make a difference.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]