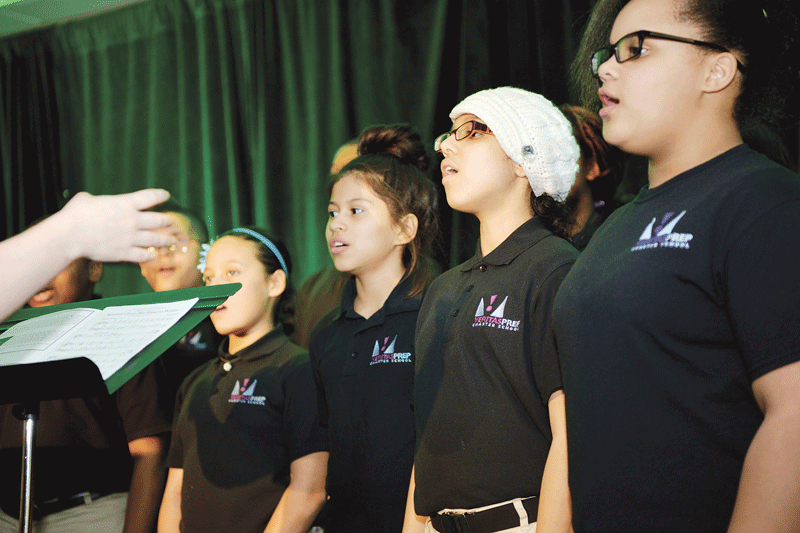

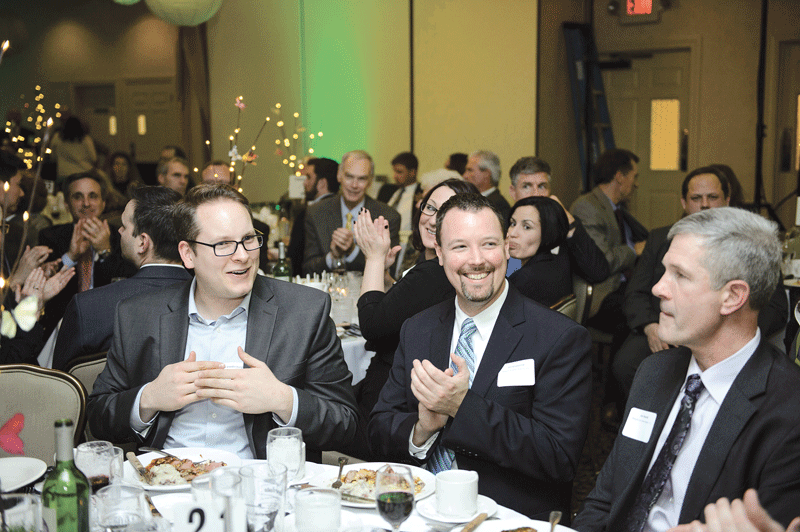

More than 450 people turned out at the Log Cabin Banquet & Meeting House in Holyoke on March 31 for a celebration of the 2016 Difference Makers, the eighth annual class of individuals and organizations honored by BusinessWest for making an impact in their Western Mass. communities. The photos below capture the essence of the event, which featured entertainment from Veritas Preparatory Charter School and the Taylor Street Jazz Band, as well as fine food and thoughtful comments from the honorees. This year’s class, chosen by the editor and publishers of BusinessWest from dozens of nominations, include Hampden County Sheriff Michael J. Ashe Jr.; the late Mike Balise, Balise Motor Sales and philanthropist; Big Brothers Big Sisters of Franklin, Hampden, and Hampshire counties; Bay Path President Carol Leary; and John Robison, president of Robison Service and advocate for individuals on the autism spectrum. Once again, the honorees received glass plates handcrafted by Lynn Latimer, representing butterflies, the symbol of BusinessWest’s Difference Makers since the program was launched in 2009.

Class of 2016

Scenes From the Eighth Annual Event

More than 450 people turned out at the Log Cabin Banquet & Meeting House in Holyoke on March 31 for a celebration of the 2016 Difference Makers, the eighth annual class of individuals and organizations honored by BusinessWest for making an impact in their Western Mass. communities. The photos below capture the essence of the event, which featured entertainment from Veritas Preparatory Charter School and the Taylor Street Jazz Band, as well as fine food and thoughtful comments from the honorees. This year’s class, chosen by the editor and publishers of BusinessWest from dozens of nominations, include Hampden County Sheriff Michael J. Ashe Jr.; the late Mike Balise, Balise Motor Sales and philanthropist; Big Brothers Big Sisters of Franklin, Hampden, and Hampshire counties; Bay Path President Carol Leary; and John Robison, president of Robison Service and advocate for individuals on the autism spectrum. Once again, the honorees received glass plates handcrafted by Lynn Latimer, representing butterflies, the symbol of BusinessWest’s Difference Makers since the program was launched in 2009. Photos by Leah Martin Photography

More than 450 people turned out at the Log Cabin Banquet & Meeting House in Holyoke on March 31 for a celebration of the 2016 Difference Makers, the eighth annual class of individuals and organizations honored by BusinessWest for making an impact in their Western Mass. communities. The photos below capture the essence of the event, which featured entertainment from Veritas Preparatory Charter School and the Taylor Street Jazz Band, as well as fine food and thoughtful comments from the honorees. This year’s class, chosen by the editor and publishers of BusinessWest from dozens of nominations, include Hampden County Sheriff Michael J. Ashe Jr.; the late Mike Balise, Balise Motor Sales and philanthropist; Big Brothers Big Sisters of Franklin, Hampden, and Hampshire counties; Bay Path President Carol Leary; and John Robison, president of Robison Service and advocate for individuals on the autism spectrum. Once again, the honorees received glass plates handcrafted by Lynn Latimer, representing butterflies, the symbol of BusinessWest’s Difference Makers since the program was launched in 2009. Photos by Leah Martin Photography

Sponsored by:

A chorus of young singers from Veritas Preparatory Charter School in Springfield kicks off the evening’s festivities.

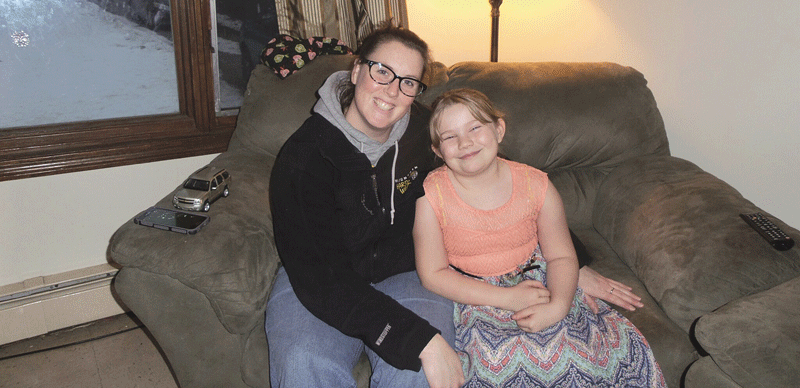

From 2016 Difference Maker Big Brothers Big Sisters (BBBS): from left, Angela Smith-LeClaire; her ‘little,’ Abby; Executive Director Danielle Letourneau-Therrien; and Kate Lockhart, all of BBBS of Hampshire County; and Ericka Almeida from BBBS of Franklin County.

Marisa Balise (left) and Maryellen Balise, daughter and wife, respectively, of Difference Maker Mike Balise.

Representing event sponsor Northwestern Mutual, from left: Nico Santaniello, Dan Carmody, and Darren James.

Bill Hynes, Baystate Health Foundation (left), and Hector Toledo, People’s United Bank.

Deborah Leone with 2013 Difference Maker James Vinick, Moors & Cabot Inc.

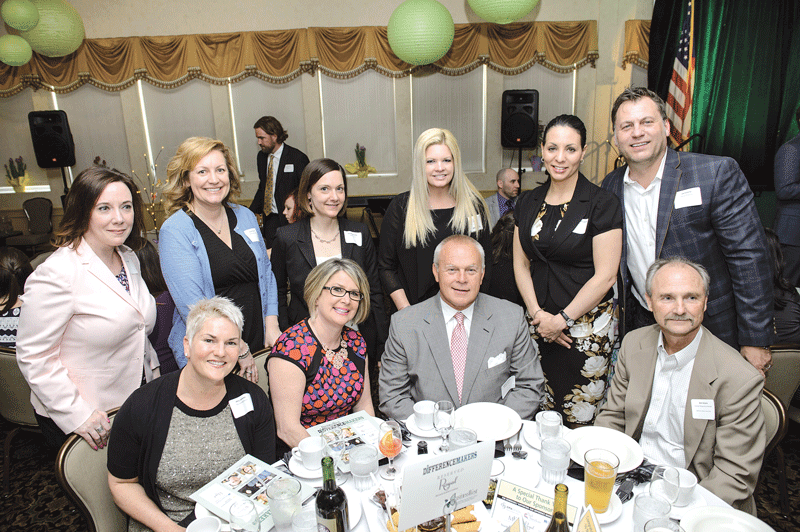

Back row: from event sponsor Royal, P.C., from left: Julie Cowan, Sarah Reece, Shawna Biscone, Founding Partner Amy Royal, Tanzi Cannon-Eckerle, Joe Eckerle. Front row: from left, Amy Jamrog, the Jamrog Group; Dawn Creighton, Associated Industries of Massachusetts; Mike Williams, Royal, P.C.; and 2010 Difference Maker Don Kozera, Human Resources Unlimited.

From event sponsor EMA Dental, from left: owners Dr. Vincent Mariano and Dr. Lisa Emirzian, Christine Gagner, Colleen Nadeau, Amy Postlethwait, Dr. Rebecca Cohen, and Dr. Colleen Chambers.

Back row, from left: from event sponsor First American Insurance, Edward Murphy, President Corey Murphy, Chris Murphy, and Molly Murphy; and Jim Fiola, Westwood Advertising. Front row, from left: from First American Insurance, Amber Letendre, Jenna Dziok, Alicja Modzelewski, Dina Potter, and Noni Moran.

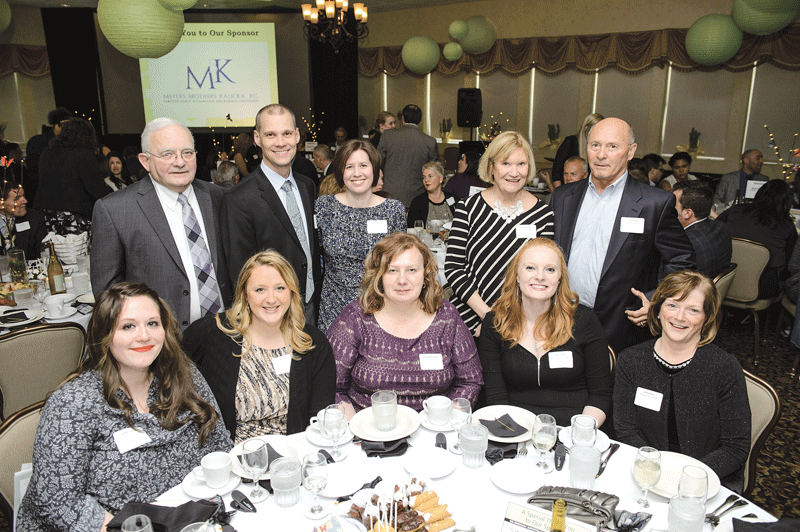

From event sponsor Meyers Brothers Kalicka, P.C., back row, from left: Brandon Mitchell, Managing Partner Jim Barrett, Kristi Reale, Joe Vreedenburgh, and Jim Krupienski. Front row, from left: Howard Cheney, Donna Roundy, and Melyssa Brown.

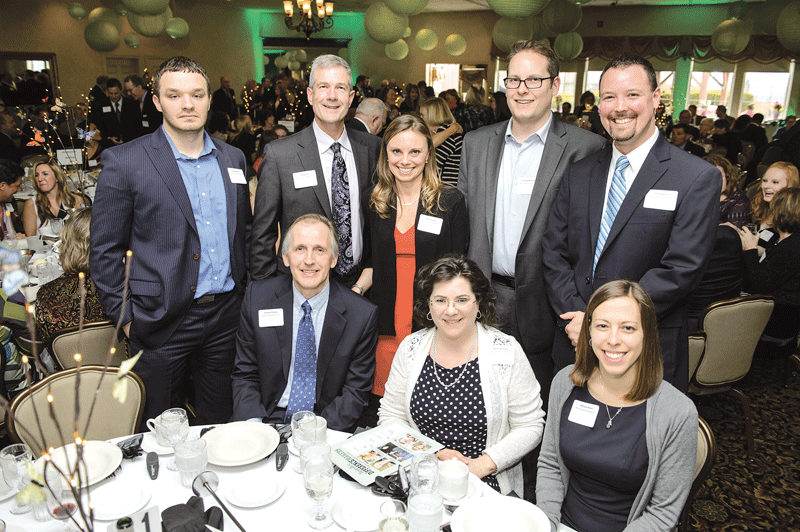

Representing event sponsor PeoplesBank, back row, from left: Xiaolei Hua, President Tom Senecal, Meghan Parnell-Gregoire, Matt Krokov, Cindy Wszolek, and Mary Meehan. Front row, from left: Shaun Dwyer, 2009 Difference Maker Doug Bowen, Anna Bowen, and Matthew Bannister.

From event sponsor Health New England, back row, from left: Dan Carabine, Steven Webster, Elaine Mann, Rosa Chelo, and Sandra Bascove. Front row, from left: Brooke Lacey, Aracelis Rivera, Sandra Ruiz, and Nicole Santaniello.

Back row, from left: Jill Monson-Bishop, Inspired Marketing; Darren James and Nico Santaniello, event sponsor Northwestern Mutual; and Heather Ruggeri, Inspired Marketing. Front row, from left: Daryl Gallant, Joe Kane, Donald Mitchell, and Dan Carmody, Northwestern Mutual.

From event sponsor Sunshine Village, back row, from left: Jeff Pollier, Michelle Depelteau, Marie Laflamme, and Ernest Laflamme. Front row, from left: Colleen Brosnan, Richard Klisiewicz, and Executive Director Gina Kos from Sunshine Village, and Chicopee Mayor Richard Kos.

From event sponsor Meyers Brothers Kalicka, P.C., from left: Joe Vreedenburgh, Jim Krupienski, and Managing Partner Jim Barrett.

Brenda Olesuk from Meyers Brothers Kalicka, P.C., an event sponsor.

David Beturne, executive director, Big Brothers Big Sisters of Hampden County, and his wife, Julie.

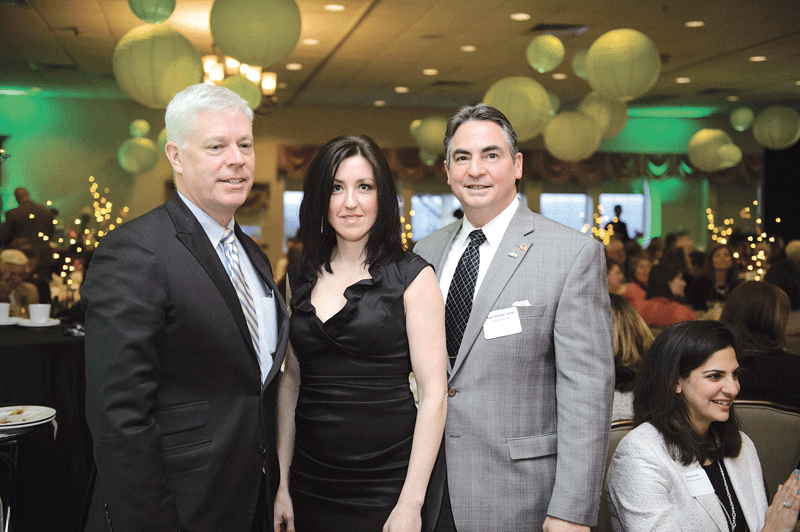

From left: Western Mass. Economic Development Council President and CEO Rick Sullivan, BusinessWest Associate Publisher Kate Campiti, and Springfield Mayor Domenic Sarno.

2016 Difference Maker John Robison, who could not attend the event, addresses the audience remotely.

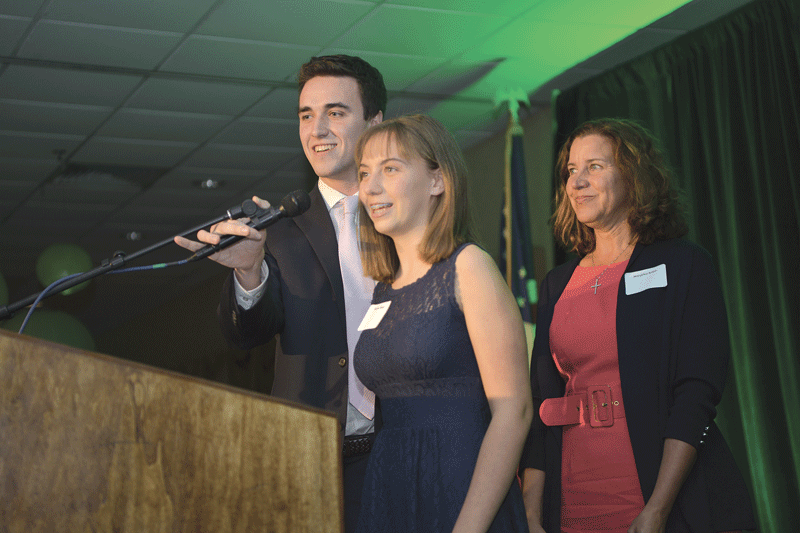

Jack Robison, son of 2016 Difference Maker John Robison, speaks about his father’s life and work on behalf of individuals on the autism spectrum.

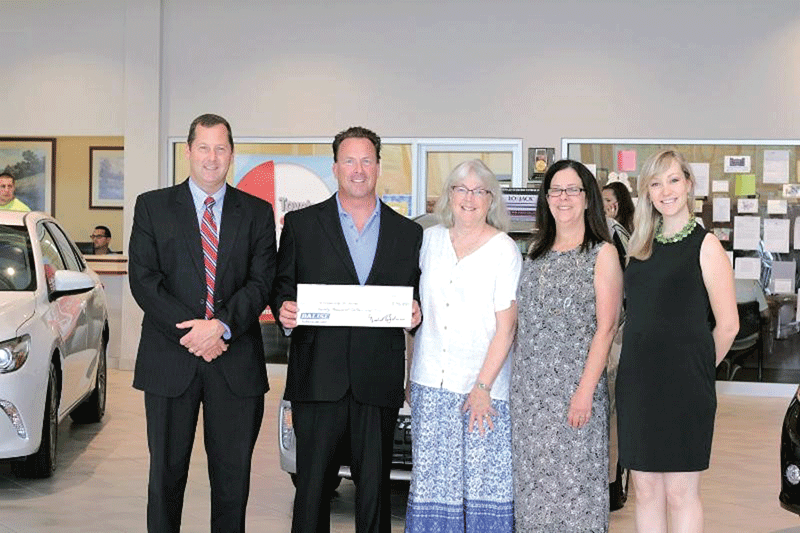

Mike Balise, honored posthumously as a 2016 Difference Maker, is memorialized by, from left, his children David and Marisa, and his wife, Maryellen.

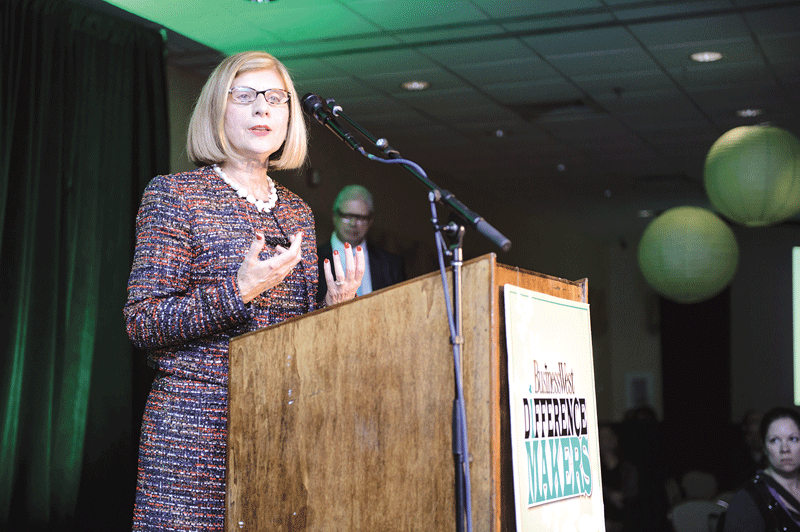

Carol Leary, honored as a 2016 Difference Maker, addresses the packed room at the Log Cabin.

2016 Difference Maker Sheriff Michael J. Ashe Jr. takes in the evening’s presentations.

A Note From Our Sponsors …

EMA Dental

First American Insurance

Health New England

Meyers Brothers Kalicka, P.C.

Northwestern Mutual

PeoplesBank

Royal, LLP

Sunshine Village

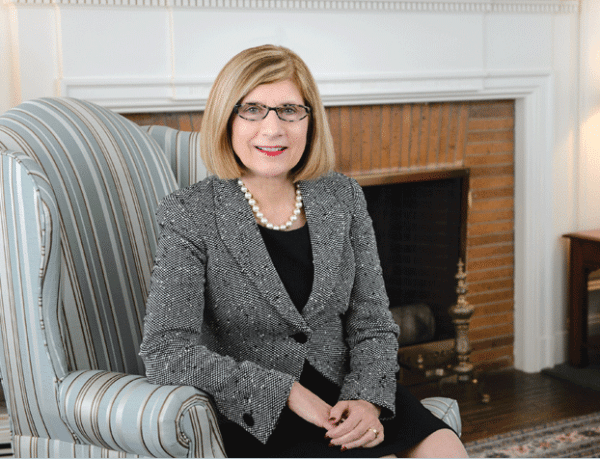

This Inspirational Leader Isn’t in the Community; She’s of the Community

Carol Leary, President of Bay Path University

Leah Martin Photography

Carol Leary says the executive search firms, the headhunters, don’t call very often any more. In fact, she can’t remember the last time one of them did.

She still gets e-mails gauging her interest in various positions, but they’re almost always of that variety that goes out to hundreds, if not thousands, of people. “Are you interested in, or would you care to nominate someone for, the job of president of ‘fill-in-blank college’” is how they usually start.

But not so long ago, Leary, who took the helm at Bay Path University in Longmeadow in late 1994, was getting calls all the time, most of them related to attractive opportunities within the broad realm of higher education. She declined to get into specifics, but said one of them was “very, very flattering.”

Still, it met with the same response as all the others — no response.

When asked why, Leary offered an answer that went on for some time. Paraphrasing that response, she said she was in a job — and in a community — that she was very committed to. And she had, and still has, no intention of leaving either one.

“Noel and I are not dazzled by big or prestigious; we’re dazzled by mission, vision, and making an impact,” said Leary, referring to her husband of 43 years. “We really love this community. We think you can make an impact here; you can make a difference.”

And the evidence that she has done just that is everywhere.

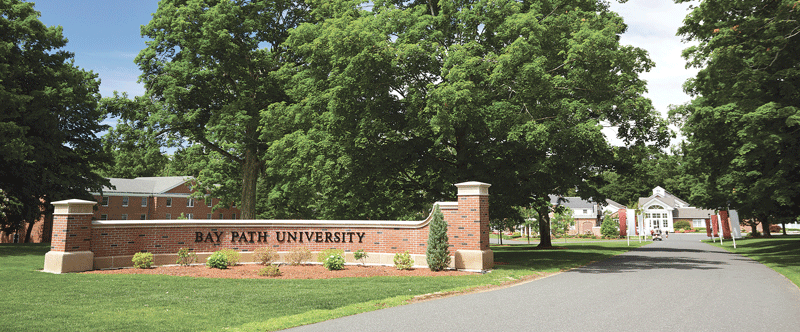

It is in every corner of the Longmeadow campus, starting with the brick sign at the front gate, which declares that this nearly 120-year-old institution, once known as a junior college, is now a university.

Carol Leary is where she always is — the middle of things — after a recent Bay Path commencement exercise.

It also exists in the many other communities where Bay Path now has a presence, including Springfield, where the school located its American Women’s College Online in a downtown office tower in 2013, and East Longmeadow, where it opened the $13.7 million Phillip H. Ryan Health Science Center a year ago.

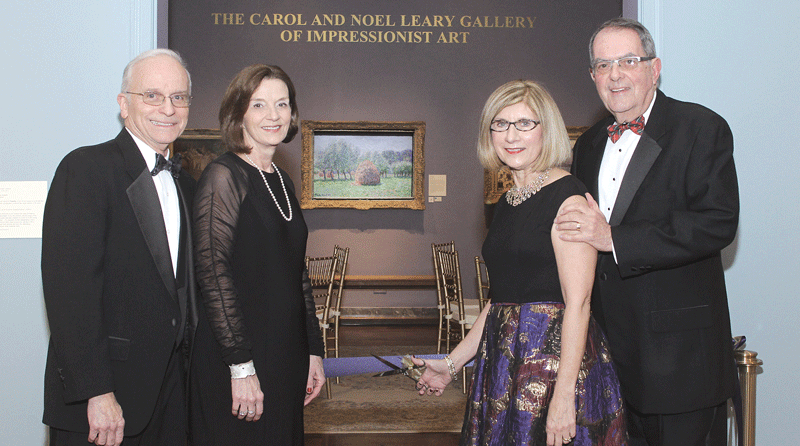

It’s also on the recently unveiled plaque at the D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts at the Quadrangle, the one that reads ‘The Carol and Noel Leary Gallery of Impressionist Art’ in recognition of their $300,000 contribution to that institution, which Noel has served as a board member for many years.

And, in a way, it’s in virtually every business and nonprofit in the region — or, to be more specific, any organization that has sent employees to the Women’s Professional Development Conference, which Leary initiated amid considerable skepticism (even at Bay Path) soon after her arrival.

When the conference was first conceptualized, organizers were hoping to draw 400 people; 800 turned out that first year. Today, the event attracts more than 2,000 attendees annually, and over the years it has welcomed keynoters ranging from Margaret Thatcher to Barbara Walters to Maya Angelou.

But Leary is best known for the turnaround story she is very much still writing at Bay Path, a school that was struggling and suffering from declining enrollment when she arrived.

Over the past two decades, she has led efforts that have taken that enrollment from just under 500 to more than 3,000 when all campuses and all programs, including online offerings, are considered. When she arrived, the school offered 14 associate degrees and three baccalaureate degrees; now, it offers 62 baccalaureate degrees and 20 graduate and post-graduate degrees.

In 2015, for the second year in row, the Chronicle of Higher Education included Bay Path on its list of the fastest-growing baccalaureate colleges in the country, and just a few months ago, Leary and Bay Path were ranked 25th in the 2015 ‘Top-100 Women-led Businesses in Massachusetts’ compilation sponsored by the Boston Globe and the Commonwealth Institute.

The sign at the main entrance explains just how far Bay Path has come under Carol Leary’s stewardship.

Such growth and acclaim didn’t come overnight or very easily, said Leary, who attributed the school’s success to vision, assembling a focused, driven team (much more on that later), and a responsive boards of trustees — all of which have facilitated effective execution of a number of strategic plans.

“Let’s see … there was Vision 2001, and 2006, and 2011, which we had to redo halfway through because of the crash, so there was 2013, and Vision 2016, which ends in June, and then we just launched Vision 2019,” she said, adding that she would like to be around for its end.

“I’ll do it only as long as my board wants me and the faculty and staff feel I can be effective as their leader,” she explained. “And as long as I can get up every day and say ‘wow, it’s great to go to work today.’”

She’s said that since day one, and it’s an attitude that only begins to explain why she’s a Difference Maker.

Making a Course Change

Leary told BusinessWest that, with few exceptions, all of them recently and schedule-related, she has interviewed the finalists for every position on campus, from provost to security guard, since the day she arrived on campus, succeeding Jeanette Wright, who passed away months earlier.

And there’s one question she asks everyone.

She wouldn’t divulge it (on the record, anyway) — “if I did, then someone might read this, and then they’d be prepared to answer it if they ever applied here” — but did say that it revealed something important about the individual sitting across the table.

“To me, that’s the most important part of any CEO’s job — the hiring of the individuals who will be working in the organization,” she explained. “Beyond the résumé and the skill set, I dig a little deeper. And my question tells me what that person cares about; it tells me what motivates them.”

The practice of interviewing every job finalist — but not her specific question of choice — was something Leary took with her from Simmons College, where she spent several years in various positions, including vice president for Administration and assistant to the president, the twin titles she held at the end of her tenure.

But that’s not all she borrowed from that Boston-based institution. Indeed, the Women’s Conference was based on an event Simmons started years earlier, and Leary has also patterned Bay Path’s growth formula on Simmons’ hard focus on diversity when it comes to degree programs.

She applied those lessons and others while undertaking a turnaround initiative at Bay Path that almost never happened — because Leary almost didn’t apply.

“I sent in my letter of interest and résumé on the last day applications were due,” she told BusinessWest, adding that she was encouraged to apply by others who thought she was ready and able to become president of a college — especially this one — but very much needed to be talked into doing so.

“I was nominated for this job — I wasn’t even looking for a presidency,” she went on, adding that, while she had her doctorate and “six years in the trenches,” as she called it, she wasn’t sure she was ready to lead a college. “I loved Simmons, I loved my job, I loved the mission, and I loved working in Boston; it was great.”

It was with all that love as a backdrop that she and Noel, while returning to Boston from a vacation in Niagara Falls that August, decided to swing through the Bay Path campus to get a look at and perhaps a feel for the institution. Suffice it to say they liked what they saw, heard, and could envision.

Indeed, what the two eventually found beyond the idyllic campus located in the heart of an affluent Springfield suburb was a college that possessed what Leary described using that time-honored phrase “good bones.”

And by that, she meant that it still had a sound reputation — years earlier, it was regarded as one of the top secretarial schools in the Northeast, if not the country — and, perhaps more importantly, a solid financial foundation upon which things could be built.

“I knew that Bay Path had been challenged with a decrease in its enrollment over several years,” she recalled. “But all the presidents had kept the institution financially strong; they kept deferred maintenance down, and the endowment was healthy for such a small school of 500 students. I looked at their programs, and I saw the challenges they were facing. But I looked at the balance sheet, and we both said, ‘we can see ourselves here; this has incredible potential as a women’s college.’”

When asked about those struggles with enrollment, Leary said they resulted in part from the fact that there was declining interest in women’s colleges, fueled in part by the fact that most every elite school in the country was by that time admitting women, giving them many more options. But it also stemmed from the fact that Bay Path simply wasn’t offering the products — meaning baccalaureate and graduate degrees — that women wanted, needed, and were going elsewhere to get.

So she set about changing that equation.

But first, she needed to assemble a team; draft a strategic plan for repositioning the school; achieve buy-in from several constituencies, but especially the board of trustees; effectively execute the plan; and then continually amend it as need and demand for products grew.

Spoiler alert (not really; this story is well known): she and those she eventually hired succeeded with all of the above.

To make a long story short, the college soon began adding degree programs in a number of fields, while also expanding geographically with new campuses in Sturbridge and Burlington, and technologically. It’s been a turnaround defined by the terms vision, teamwork, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

Milestones along the way include everything from the establishment of athletics (there are eight varsity sports now) to the first graduate-degree program (Communications and Information Management), launched in 2000, a year ahead of schedule; from the introduction of the innovative One-Day-a-Week Saturday College to those new campuses; from the launching of the American Women’s Online College to the school’s being granted status as a university in 2014.

Add it all up, and Leary and her staff have accomplished the mission she set when she arrived — to make Bay Path a destination.

That’s a great story, but the better one — and the reason why all those executive search firms were calling her — is the manner in which all this was accomplished.

Study in Relationship Building

And maybe no one can explain this better than Caron Hoban.

She didn’t work directly with Leary at Simmons — they were assigned to different campuses but served together on a few committees — but certainly knew of her. And when Leary went to Bay Path, Hoban decided to follow just a few months later.

“I knew her a little bit, and I was looking to make my next move just as she had been made president at Bay Path; they had a position open, and I applied for it,” said Hoban, who now holds the position of chief strategic officer.

When asked to summarize what Leary has accomplished at the school and attempt to put it all in perspective, Hoban obliged. But is doing so, she focused much more on how Leary orchestrated such a turnaround and, perhaps even more importantly, why.

And as she articulated these points, Hoban identified what she and others consider Leary’s greatest strengths — listening and forging partnerships.

“One of her greatest gifts is relationship building,” Hoban explained. “So when she came to Bay Path and the Greater Springfield area 21 years ago, she really committed to not just learning more about the college, but really understanding the whole region. She met with hundreds and hundreds of people and just listened.

“At my first meeting with her, she said, ‘what I’ve really been trying to do in my early days is listen to people and understand what the college needs and what the region needs,’” Hoban went on, adding that from this came the decision to create a women’s professional conference modeled on the one at Simmons, and a commitment to add graduate programs in several areas of study.

“She knew that the way to grow the campus and move from 500 students, which is what we had when she arrived, to the 3,000 we have now is by adding master’s-degree programs,” Hoban went on. “And these came about by her going out and listening to what the workforce needs were in the community.”

But Hoban said Leary’s listening and relationship-building talents extended to the campus community, the people she hired, and her own instincts, and this greatly facilitated what was, in every aspect of the word, a turnaround that was critical to the school’s very survival.

In 2007, President Leary welcomed poet, author, and civil-rights activist Maya Angelou to the Women’s Leadership Conference.

Indeed, in 1996, Leary recalled, she essentially asked the board for permission to spend $10 million of the $14 million the school had in the bank at the time over the next several years to hire faculty, add programs, and, in essence, take the school to the next level.

“I remember the conversations that were had around the table, and there was one member of the board, the chair of the academic committee, who said, ‘if we don’t do this, there might not be a future for Bay Path,’” she recalled. “I recommended that we make that investment — it had athletics in it, the Women’s Leadership Conference, and much more; that was Vision 2001.”

As it turned out, she didn’t have to spend all the money she asked for, because those degree programs added early on were so successful that revenues increased tremendously, to the point where the school didn’t have to take money out of the bank.

Looking back on what’s transpired at Bay Path, and also at the dynamics of administration in higher education, Leary said turning around a college as she and her team did is like turning around an aircraft carrier; in neither case does it happen quickly or easily.

In fact, she said it takes at least a full decade to blueprint and effectively execute a turnaround strategy, and that’s why relatively few colleges fully succeed with such initiatives — the president or chancellor doesn’t stay long enough to see the project to completion. And, inevitably, new leadership will in some ways alter the course and speed of a plan, if not create their own.

But Leary has given Bay Path not one decade, but two, and she’s needed all of that time to put the school on such lists as the Chronicle of Higher Education’s compilation of fastest-growing schools.

In keeping with her personality, Leary recoils when a question is asked with a tone focusing on what she has done. Indeed, she attributes the school’s progression to hiring the right people and then simply providing them with the tools and environment needed to flourish.

“I got up every day and knew I had to hire the best possible staff, people who believed in the mission,” she recalled. “And when people ask why Bay Path has been so successful, I say it’s because I hired the right people at the right time, and they just threw themselves into their jobs.”

While giving considerable credit to those she’s interviewed and hired over the years, Leary saved some for Noel and his willingness to share what she called “an equal-opportunity marriage.”

Elaborating, she said she agreed to uproot and follow him to Washington, D.C. and a job in commercial real estate there decades ago, and he more than reciprocated by first following her to Boston as she took a job at Simmons, then making another major adjustment — trying to serve his clients in the Hub from 100 miles away — when she came to Bay Path. He did that for more than a decade before retiring and taking on the role of supporting her various efforts.

“Noel has been a tremendous, tremendous support to me,” she explained. “He basically said, ‘this is an important job, I love what you’re doing, and I enjoy being a part of it.’”

And she implied that what he meant by ‘it’ was not simply her work at the campus on Longmeadow Street, but her efforts well outside it. They are so numerous and impactful that Hoban chose to say that Leary isn’t in the community, “she’s of the community.”

And perhaps the best example of that has been the women’s conference and how the region’s business community has embraced it.

Learning Curves

Dena Hall says it’s a good problem to have. Well … sort of.

There are more people at United Bank, which Hall serves as regional president, who want to go to the conference than the institution can effectively send.

Far more.

And that has led to some hand-wringing among those administrators (like Hall) whose job descriptions now include deciding who gets to go each spring and who doesn’t.

“We’ve gotten to the point where we have too many who want to go — we just can’t accommodate everyone, because we can’t have 50 current or emerging leaders out of the company at one time,” she explained. “So we’ve put it on each of our managers to identify one or two women in their business line who they believe should attend the conference and who will really benefit from what they see and hear.”

But these hard decisions comprise the only thing Hall doesn’t like about the women’s conference, except maybe finding a parking space that morning. That, too, has become a challenge, but, for the region as a whole, also a great problem to have.

Because that means that 2,000 women — and some men as well — are not only hearing the keynoters such as Walters, Angelou, and others, but networking and learning through a host of seminars and breakout sessions.

“You always learn something,” said Hall, who has been attending the conference for more than a dozen years. “Last year, I participated in the time-management workshop, and it changed the entire way I look at my schedule from Monday through Friday; the woman was fantastic.

“And there’s tons of networking,” she went on. “We use the conference here as a coaching and development tool for the more junior women on our team. There’s a lot of value in it, and for us, the fact that it’s five minutes away makes it so much easier than sending someone to Boston or New Haven or anywhere else.”

The conference is a college initiative — indeed, its primary goal beyond the desire to help educate and empower women is to give the school valuable exposure — but it is also a community endeavor, and one of many examples of how Leary is of, not just in, the community.

Others include everything from her service to the Colony Club — she was the first woman to chair its board — to her time on the boards of the Community Foundation, the Beveridge Foundation, WGBY, and United Bank, among others. She was also the honorary chair of Habitat for Humanity’s All Women build project in 2009.

And then, there was the support she and Noel gave to the museums and the current capital campaign called “Seuss & Springfield: Building a Better Quandrangle,” a gift that Springfield Museums President Kay Simpson described as not only generous, but a model to others who thought they might not be able to afford such philanthropy.

“One of the motivating factors for Carol and Noel,” she noted, “is that they wanted to demonstrate that, even if you don’t think you can make a substantial gift, with planning, you can do it.”

Leary said planning began years ago, and was inspired by a desire to preserve and expand a treasure that many in this area simply don’t appreciate for its quality.

“We really believe in the museum — we absolutely adore it,” she said. “I said to my niece and nephew at the gala [where the gift was announced], ‘this is your inheritance; you might be in the will, but there isn’t going to be any money in it — it’s going right here, so you can bring your children and your children’s children here decades from now.’

“Noel told the audience that night, ‘we have some big birthdays coming up, but forget Tiffany’s; we’re giving it to the museums,’” she went on. “That’s how much we think of this region; there are so many gems, like the museums, the symphony, CityStage, and others that need support.”

From left, Donald D’Amour, Michele D’Amour, Carol Leary, and Noel Leary at the ceremony marking the naming of the Gallery of Impressionist Art.

And looking back on her time here, she said it has been her mission not only to be involved in the community herself, but to get the college immersed in it as well. She considers these efforts successful and cites examples of involvement ranging from Habitat for Humanity to Big Brothers Big Sisters; from Link to Libraries to the college’s sponsorship of the recent Springfield Public Forum and partnerships that brought speakers such as Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor and author Wes Moore.

“You can’t be an ivory tower,” she told BusinessWest. “We have to be part and parcel of the good, the bad, and the ugly of any community.”

As she talked about the importance of involvement in this community, Leary made it a point to talk about the region itself, which she has chosen to call home. She said it has attributes and selling points that are easier for people not from the 413 area code to appreciate.

And this is something she would like to see change.

“People underrate this area, and the negativity has to stop,” she said with twinges of anger and urgency in her voice. “The language and the perception has to start changing from all of us who have a voice; we have to talk more positively.”

A Class Act

When asked how long she intended to stay at the helm at Bay Path, Leary didn’t give anything approaching a specific answer other than a reference to wanting to see how Vision 2019 shakes out.

Instead, she conveyed the sentiment that was implied in all those non-responses to inquiries from executive search firms: she’s not at all ready to leave this job or this community.

As she said, one can have an impact here. One can make a difference.

Not everyone does so, but she has, and in a number of ways.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]

His Efforts on Behalf of the Autistic Are a Global Phenomenon

John Robison, President of J.E. Robison Service

Leah Martin Photography

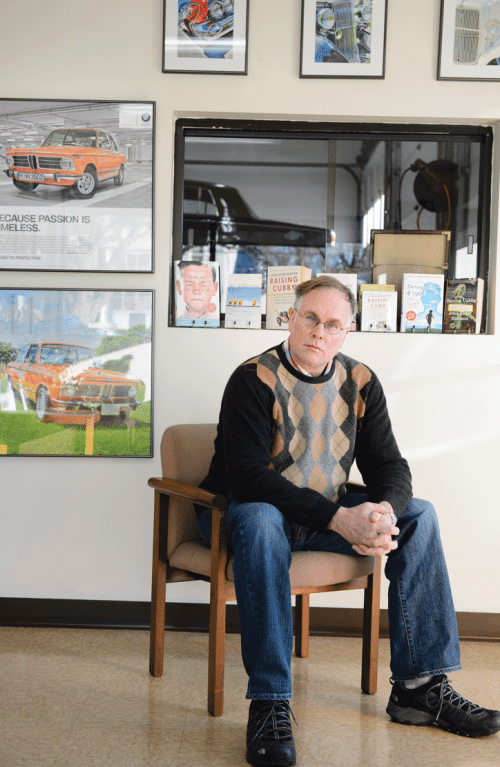

On the sill of the window in the front office at JE Robison Service, the one that offers a view into a long row of service bays that hosted Jaguars and Land Rovers, sits a display of the three books written by the company’s founder, John Robison, about Asperger’s syndrome and his life with that condition.

In chronological order, these would be Look Me in the Eye, which archives his life growing up; Be Different, which offers practical advice for Aspergians; and Raising Cubby, a memoir of his unconventional relationship with his son, who was also born with Asperger’s.

Near the middle of the display is a book with the title Wychowujemy Misiaka, which, says Robison, is the Hungarian version of Raising Cubby, only he doesn’t know if that’s a direct translation of those two words; a book will often take another title when published in a foreign country. For example, the Dutch version of Look Me in the Eye is titled I Always Liked Trains Better.

Meanwhile, there’s another book written in Russian; Robison thinks it’s Look Me in the Eye, but he admits he’s not sure and knows only that it’s one of his.

While the display creates some questions and confusion, it makes it abundantly clear that Robison’s efforts to raise awareness of disorders in what’s known as the autism spectrum, and advocate for the estimated 5 million people living with such conditions, are now a truly global phenomenon.

It’s an initiative with many moving parts — from the books to his numerous speaking engagements around the country; from a program at his foreign-car sales and service shop to train people with autism to be auto mechanics, to his participation on a number of panels created to help define the autism spectrum and improve quality of life for those who populate it.

John Robison says awareness that his differences stemmed from Asperger’s was empowering and liberating.

Leah Martin Photography

Indeed, Robison now represents the tip of the spear in a movement, for lack of a better term, that he and others are calling ‘neurodiversity,’ or neurological diversity, and all that this phrase connotes.

“This is the idea that neurological diversity is an essential part of humanity, just as racial, cultural, religious, or sexual diversity are,” Robison explained as he sat on a couch in that front office. “Those are all accepted things, and now we recognize that conditions like autism have always been with us, and we recognize that some autistic people are profoundly disabled — and indeed I’m disabled in many ways. But I’m also gifted in many ways, and that’s what people need to understand; autistic people have unique contributions to make to the world because of their difference, and the world needs that.”

While speaking on this subject, Robison also drives home the point that individuals within the spectrum — like those protected classes he mentioned — have a right, like those other groups, to be free from profiling and discrimination. And, at present, they are not.

As just one example, he cited one of the many mass-shooting episodes that have become commonplace in this country.

“The big thing about autism is how we’re treated related to other groups,” he explained. “I recall reading in the newspaper about how a bunch of people were murdered, and it said that the killer was on the autism spectrum.

“That’s a familiar headline for people, stuff like that,” he went on. “Can you imagine what would happen if someone went on the nightly news and said ‘seven people were murdered at a shopping center in Hartford today, and the killer was a Jew’? That guy would lose his job tomorrow. And yet someone can go on the news and say ‘seven people were killed in a theater, and the killer had autism.’

“Autism is no more predictive of mass murder than being Jewish,” he continued, adding that there is much work to do simply to make this fact known and fully understood, let alone prompt society to embrace neurodiversity, or the concept that society should accept people whose brains function in many different ways.

For doing that hard work, in many different ways, Robison can add the title Difference Maker to the several he already has.

Mind over Matter

There will soon be a fourth book competing for space on that shelf in Robison’s office.

It’s called Switched On, and its subject matter represents a radical departure from his previous works. This tome, finished several months ago, chronicles Robison’s participation in experiments at Harvard Medical School and Boston’s Beth Israel Hospital involving transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). The treatment is aimed at changing emotional intelligence in humans by firing pulses of high-powered magnetic energy into the brain to “help it re-wire itself,” said the author.

Those experiments, conducted from 2008 to 2010, yielded a mixed bag of results, said Robison, who explained, in some detail, what he meant by that.

“I think it succeeded beyond their wildest hopes in some ways,” he said of the regimen. “But as much as it turned on abilities in me, that came at a cost. It cost me relationships, and it made me more up and down, where before, I’d been on kind of an even keel all along.

“Suddenly, I felt suffocated by my wife’s long-time depression, I felt like I was drowning, and then ultimately I wasn’t able to stay married anymore,” he went on. “And before, I’d been oblivious to what people thought and said when they came in here for service; suddenly I began to see that some people were contemptuous of me and the business, and I didn’t like that. So I dismissed a good number of people I didn’t want to do work for anymore.”

All things considered, he describes what’s happened as a good tradeoff; he says he’s more knowledgeable and has greater ability to engage people. He was going to say more, but essentially decided that, if people want to know more, they could, and should, read the book, which will be out in March.

While Robison has devoted much of the past few years to this latest tome, he’s devoted much of his adult life to many types of work involving the autism spectrum.

That work started roughly the day he found out he was part of that population, he went on, adding that he didn’t know he belonged until a self-diagnosis, if one could call it that, several years ago that was spurred by one of his foreign-car customers.

Before detailing that episode, though, we need to back up a little and explain how Robison arrived there, because doing so helps explain his passion for what you might call his ‘other work.’

John Robison says much of his current work involves the emerging concept of neurodiversity.

His career track then took a sharp turn, and he ventured into the corporate world, first as a staff engineer at Milton Bradley in the late ’70s, and later as chief of the power-systems division for a military laser company. But while he had the technical know-how to succeed in those environments, he was missing the requisite social, interactive skills, including the simple yet important ability to look people in the eye.

“I didn’t fit in at large corporations,” he explained. “I didn’t say the right things, I got into trouble, I would say inappropriate things, I was rude. But, at the same time, I was a good engineer; I look at the stuff that I designed in rock ‘n’ roll and the toy industry with Milton, and I think my engineering work speaks for itself, even today.

“But I had significant social problems, and therefore I felt that I was a failure in electronics because of those things and because I couldn’t read other people,” he went on. “So I decided that, if I was failing at electronics, I would start a business where I wouldn’t be subject to being just dismissed; that’s what made me turn to fixing cars.”

And, eventually, selling them, restoring them, and connecting people with them. Indeed, his venture deals in high-end foreign makes and hard-to-find vehicles. He started working out of his home in South Hadley, later moved into space on Berkshire Avenue in Springfield, and now has what amounts to a complex on Page Boulevard.

The business grew to the point where he hired mechanics to handle the cars, and his work shifted toward operations, ordering parts, and dealing with customers. One of them, a regular, was a therapist, and during one discussion with him, the subject turned to Asperger’s. The therapist eventually gave Robison a book on the subject, one of many he would soon devour.

It was that reading that opened his eyes and eventually brought him to what can only be considered a global stage when it comes to advocacy for those on the autism spectrum.

A New Chapter

“It was a remarkable thing,” he recalled of the events that led him to understand why he was the way he was, even though a formal medical diagnosis would come later. “I learned things like autistic people have difficulty looking other people in the eye; it makes us uncomfortable. So, all my life, people had said things like, ‘look at me when I talk to you.’ I would look up and then quickly down, and I had no idea that other people were different in that regard.

“I felt all my life I was complying with what other people said, and yet they continued to be after me about it,” he went on. “It was only after reading that book that I understood how certain things that I did, like that, were different from what other people expected, and it’s because I was neurologically different. No matter how smart you are, you can’t possibly just figure that someone else sees the world differently than you do. So that book was life-changing.”

And as he talked about the process of discovering the cause of his “own differences,” as he called them, Robison used the words ‘empowering’ and ‘liberating’ to describe the phenomenon.

And as he talked about the process of discovering the cause of his “own differences,” as he called them, Robison used the words ‘empowering’ and ‘liberating’ to describe the phenomenon.

“If you’ve been told that you’re lazy, stupid, retarded, defective, or no good, for you to learn that you are touched by a form of autism, that’s … an explanation, and that’s really good,” he said, adding that, with this explanation, he would learn the ways autistic people (including those with Asperger’s) were different, and “teach myself to behave more like people expected.”

This was a transformative change, he went on, adding that he became more accepted in the community and forged real friendships, and this helped inspire his gradual development as an advocate, work that could be summed up as efforts to provide others with those same feelings of empowerment and liberation.

He said ‘gradual’ for a reason, because this work has certainly evolved over the years.

It began with speaking engagements to groups of young people at venues like Brightside for Families & Children and youth-detention facilities. The talks focused on autism, but also on Robison’s childhood, one marked by various forms of abuse.

“I realized that I could be speaking to young people about having a good life despite having that in your background, too,” he explained, adding that eventually he sought to reach a broader audience.

That led to Look Me in the Eye, an eventual bestseller published in 2006, and later his other works, all of which are now sold around the world. He believes that, worldwide, sales of the three books have topped 1 million copies.

But the books and the speaking engagements are only a few manifestations of Robison’s advocacy for people on the spectrum.

There is also the training school he’s created at his business for young people with autism. Conducted in partnership with the Northeast Center for Youth and Families, the initiative has transformed three bays at the Page Boulevard facility into what amounts to an instructional classroom for young people with learning challenges.

It was created with the goal of steering participants toward good-paying jobs in the auto-repair sector, and reflects Robison’s broader mission of transforming how people with differences should be valued and treated by society, and seen as productive contributors to society.

Other forms of service — and they often represent opportunities and appointments created through the exposure generated by his books — include participation on several boards and commissions involved with autism treatment and policy.

Four years ago, Robison was asked by then-Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius to serve on the committee that produces the strategic plan for autism for the U.S. government; that appointment has since been renewed by current HHS Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell. He also serves on a panel that evaluates autism research for the U.S. Department of Defense as well as the steering committee for the World Health Organization developing ICF (International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health) core sets for autism-spectrum disorder.

He also served a stint on a review board with the National Institutes of Health, tasked with determining how economic-stimulus money appropriated in 2008 should be spent on autism research.

While doing all that, he also teaches a class in neurodiversity at the College of William & Mary, one of the first programs of its kind in the country.

Add all that up, and Robison has a lot of frequent-flyer miles. More importantly, he has an ever-more powerful voice — one he’s certainly not afraid to use — when it comes to the rights of all those within the autism spectrum, how those rights are not being recognized or honored, and how all that has to stop somehow.

It all starts with recognition of those rights, he said, adding quickly that discrimination against those in the autism spectrum is more difficult to recognize because most people don’t see it as discrimination.

As one example, he cited educational testing, a realm where discrimination against some classes has been identified — because of which questions are asked and how — and, in many cases, addressed. Not so when it comes to those with autism.

“You could administer a math or reading test to someone like me, and because I can’t do math problems in the conventional way, I would fail that test,” he explained. “Yet, I could solve complex problems in math in real life, like doing wave-form mathematics in the creation of sound effects when I worked in electronics.

“If you were to test a person like me in a culturally appropriate way, I’d be a bright guy,” he went on. “But if you tested me the way Amherst High School tested me, I was a failure, and there are a lot of autistic people who are like me today. That testing sets us up for future failure, and it’s a form of discrimination.”

When asked if, how, and when various forms of discrimination, such as those headlines involving mass shootings, might become a thing of the past, Robison said this constitutes a difficult task, because so many don’t even recognize it as discrimination.

Progress will only come if adults within the spectrum take full ownership of their condition. And, by doing so, they would also stand up for their rights, as he does.

“We need adults with autism to own it and to say, “I’m autistic, and I’m going to fight for my equality,” he explained, adding that is what the memnbers of various ethinic, racial, and religious groups have done throughout history.

“Autistic people need to do the same thing,” he went on. “They need to say, ‘I’m an autistic adult, and I’m here to say that we’re no killers, we’re not this, and we’re not that; we’re parts of your community everywhere.’”

Summing up what he’s been doing since his customer gave him that book all those years ago, he would say it comes down to getting other people on the spectrum to assume that ownership.

The Last Word

As he talked with BusinessWest, Robison had to stop at one point to take a call concerning flight options for an upcoming speaking engagement in Florida.

It’s fair to say he’s mastered the art and science of booking flights, finding deals, and filling a schedule in a manner that allows him to do all he needs to do.

And that’s only one example — the books on that shelf, as mentioned earlier, are another — of how his work is now truly global in scope.

He said that book he read long ago opened his eyes, empowered him, and liberated him. Helping others achieve all that and more has become a different kind of life’s work.

And another way to make a difference.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]

Their Contributions to Be Honored on March 31

The 2016 Honorees:

• Hampden County Sheriff Michael J. Ashe Jr.

• Mike Balise, Balise Motor Sales, Philanthropist (1965-2015)

• Big Brothers Big Sisters of Franklin, Hampden, and Hampshire Counties

• Bay Path University President Carol Leary

• John Robison, president, J.E. Robison Service

The old line about pictures and how they’re worth a thousand words has been around seemingly since Mathew Brady poignantly documented the Civil War.

It usually doesn’t work effectively with business journalism, but in the case of this year’s Difference Makers, it certainly rings true.

This year’s special section features a number of pictures that could be called powerful, and that certainly tell the story at least as effectively as the accompanying words.

Start with the image of Homer Street School Principal Kathleen Sullivan standing next to a lone winter jacket hanging in the main hallway of that facility. It doesn’t have an owner, because every student at the school who needs a jacket — and there are many in that category because Homer Street is in one of the most impoverished neighborhoods in the state — has one because of Mike Balise.

He succumbed to stomach cancer late last month, but not before making sure his annual donation of money for coats, started two years ago, would continue after his death.

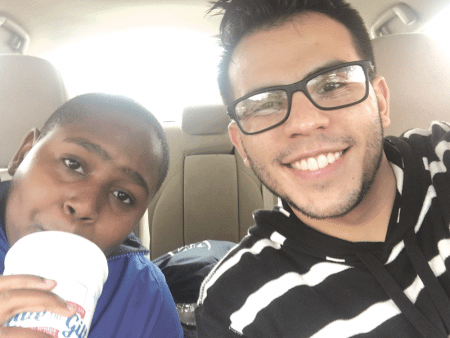

Then, there are the many images of big brothers and big sisters with their ‘littles,’ as they’re called. Individually and collectively, they effectively drive home the point of how this organization, and specifically the Franklin, Hampden, and Hampshire County chapters, work to create matches that bring stability into the lives of young people and forge friendships that last a lifetime.

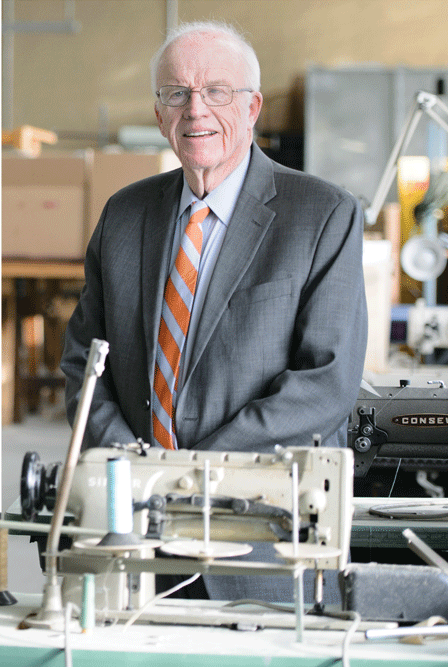

Meanwhile, the two images of Hampden County Sheriff Michael J. Ashe Jr. convey both the passage of time — he’s been in this post for more than 40 years — and how he’s taken corrections from one era, when inmates were essentially warehoused, to another, in which rehabilitation is the watchword.

There are other impactful images, including several involving Bay Path President Carol Leary. Two depict high-profile speakers who have keynoted the Women’s Professional Development Conference, and another depicts the sign at the front entrance declaring that this former junior college is now a university, one of many huge developments that occurred during her watch.

And then, there’s the image of John Robison posing near a half-million-dollar Italian sports car, a picture that depicts his success in business, as well as his determination to help others within the autism spectrum reach their full potential.

Meet the first seven classes of Difference Makers

Together, these pictures are worth several thousand words, and they collectively help explain some of the many ways in which individuals and groups in this region can make a difference.

The specific ways found and developed by members of the Difference Makers Class of 2016 are explained in far greater detail on the pages of this special section. And these contributions will be celebrated at the annual gala on March 31 at the Log Cabin Banquet & Meeting House in Holyoke.

The gala has become one of those not-to-be-missed events on the regional calendars. It is a wonderful networking opportunity, but more importantly, it is a chance to recognize those who have made a huge difference in the lives of countless others.

The March 31 gala will feature butlered hors d’oeuvres, lavish food stations, a networking hour, introductions of the Difference Makers, and remarks from the honorees. Tickets cost $60 per person, with tables of 10 available.

For more information about the event or to reserve tickets, call (413) 781-8600, ext. 100, or go HERE.

Sponsored by:

Photo portraits by Leah Martin Photography

His Career Has Been All About ‘Embracing the Challenge’

Hampden County Sheriff Michael J. Ashe Jr.

Leah Martin Photography

Since taking office back in January 1975, Michael Ashe has spent roughly 15,000 days as sheriff of Hampden County.

The one everyone remembers was that Friday in October 1990 when he led what amounted to an armed takeover of the National Guard Armory on Roosevelt Avenue in Springfield. It was mounted in response to what Ashe considered dangerous overcrowding at the county jail on York Street, built in 1886 to house a fraction of the inmates he was hosting at the time.

The incident (more on it later) garnered headlines locally, regionally, and even nationally, and in many ways it finally propelled Hampden County’s commissioners to move toward replacing York Street — although nothing about the process of siting and then building the new jail in Ludlow would be considered easy.

While proud of what transpired on that afternoon more than 25 years ago, Ashe, now months away from retirement, hinted strongly that he would much rather be remembered for what transpired on the 14,999 or so other days. These would be things that didn’t land him on the 5 o’clock news, necessarily (although sometimes they did) — but did succeed in changing lives, and in all kinds of ways.

Summing up that work, he used the phrases “embracing the challenge” and “professional excellence” for the first of perhaps 20 times, and in reference to himself, his staff, and, yes, his inmates as well.

Elaborating, he said professional excellence is the manner in which his department embraces the challenge — actually, a whole host of challenges he bundled into one big one — of making the dramatic leap from essentially warehousing inmates, which was the practice in Hampden County and most everywhere else in 1974, to working toward rehabilitating them and making them productive contributors to society.

This philosophy has manifested itself in everything from programs to earn inmates a GED to the multi-faceted After Incarceration Support Systems Program (AISSP), to bold initiatives like Roca, designed to give those seemingly out of options one more chance to turn things around.

Slicing through all those programs, Ashe said the common denominator is making the inmate accountable for making his or her own course correction and, more importantly, staying on that heading. And the proof that he has succeeded in that mission comes in a variety of forms, especially the recently released statistics on incarceration rates in Hampden County.

They show that, between September 2007, when there were 2,245 offenders in the sheriff’s custody — the high-water mark, if you will — and Dec. 31, 2015, the number had dropped to 1,432, a 36% reduction.

Some of this decline can be attributed to lower crime rates in Springfield, Holyoke, and other communities due to improved policing, but another huge factor is a reduction in the number of what the sheriff’s office calls “recycled offenders” through a host of anti-recidivism initiatives.

Like the Olde Armory Grille. This is a luncheon restaurant and catering venture (a break-even business) operated by the Sheriff’s Department at the Springfield Technology Park across from Springfield Technical Community College, and in one of the former Springfield Armory buildings, hence the name. It is managed by Cpl. Maryann Alben, but staffed by inmates engaged in everything from preparing meals to cashing out customers.

‘Bill’ (rules prohibit use of his last name) is one of the inmates currently on assignment.

He’s been working on the fryolator and doing prep work, often for the hot entrée specials, and hopes to one day soon be doing such work in what most would call the real world, drawing on experiences at the grille and also while working for his uncle, who once owned a few restaurants.

He said the program has helped him with fundamentals, a term he used to refer to the kitchen, but also life in general.

“I went from being behind the wall to being out in the community,” he said. “And now I’m into the community.”

Bill’s journey — and Ashe’s life’s work — are pretty much defined by something called the “Hampden County Model: Guiding Principles for Best Correctional Practice.”

There are 20 of them (see bottom), ranging from No. 4: “Those in custody should begin their participation in positive and productive activities as soon as possible in their incarceration” to No. 15: “A spirit of innovation should permeate the operation. This innovation should be data-informed, evidence-based, and include process and outcome measures.”

But it is while explaining No. 2 — “Correctional facilities should seek to positively impact those in custody, and not be mere holding agents or human warehouses” — that Ashe and his office get to the heart of the matter and the force that has driven his many initiatives.

“It is a simple law of life that nothing changes if nothing changes,” it reads.

By generating all kinds of change, especially in the minds and hearts of those entrusted to his care, Ashe is the epitome of a Difference Maker.

Coming to Terms

The old and the new: above, Mike Ashe at the old York Street Jail, which was finally replaced in the ’90s with a new facility in Ludlow, bottom.

Ashe told BusinessWest that, when he first took the helm as sheriff in 1975, not long after a riot at York Street, he was in the jail almost every day, a sharp departure from his current schedule.

Perhaps the image he remembers most from those early days was the white knuckles of the inmates. They were hard to miss, he recalled, as the prisoners grasped the bars of their cells, an indication, he believed, of immense frustration with their plight.

“There was a great deal of tension, and you see it in those knuckles.” he said. “Inmates had a lot of time on their hands; people were just languishing in their cells. I think the only program they had at the time was a part-time education program conducted with the Springfield School Department, an adult basic-education initiative. That was it, and it was only part-time.”

Doing something about those white knuckles has been, in many ways, his personally written job description. As he talked about everything involved with it, he spent most of his time and energy discussing how one approaches that work, using more words that he would also wear out: ‘intensity’ and ‘focus.’

Together, those nouns — as well as the operating philosophy “firm but fair, and having strength reinforced with decency” — have shaped a remarkable career, one that he freely admits lasted far longer than he thought it would when he took out papers to run for sheriff early in 1974. It’s been a tenure defined partly by longevity — since he was first elected, there have been seven U.S. presidents (he had his photo taken with one — Jimmy Carter); eight Massachusetts governors (nine if you count Mike Dukakis twice, because he had non-consecutive stints in office); and eight mayors of Springfield — but in the end, that is merely a sidebar.

So too, at least figuratively speaking, are the takeover of the Armory and the building of a new Hampden County jail, although the former was huge news, and the latter was a long-running story, as in at least 20 years, by most accounts.

Recalling the Armory seizure, Ashe said it was a back-door attempt — literally, the sheriff’s department officials gathered at the front door while the inmates were brought in through the back — to bring attention to the overcrowding issue, because all other attempts to do so had failed to yield results.

“We were trying to get people to listen, because it was clear to us that they weren’t listening,” he explained. “We went to the Armory that Friday afternoon and basically evoked a law that went back to the 1700s. Getting into the building was key; once we did that, we knew we’d get everyone’s attention.”

No, the sheriff’s story isn’t defined only by the Armory takeover or his long tenure. It involves how he spent his career working to give his staff less work to do — or at least fewer inmates to guard.

To explain the philosophy that has driven the many ways Ashe has worked to lessen that workload, one must go back to guiding principle No. 2.

“If incarceration is allowed to be a holding pattern, a period of suspended animation, those in custody are more likely to go back to doing what they have always done when they are released,” it reads, “because they will be what they have always been. The only difference may be that they have more anger and more shrewdness as they pursue their criminal career.”

Elaborating on what this principle and the others mean in the larger scheme of things, Ashe said most inmates assigned to his care have been given sentences of seven to eight months. Relatively speaking, that’s a short window, but it’s an important time. And what the sheriff’s office does with it — or, more importantly, what that office enables the inmate to do with it — will likely determine if the individual in question becomes one of those recycled offenders.

So we return once more to the second principle for insight into how Ashe believes that time should be spent.

“Most inmates come to jail or prison with a long history of social maladjustment, carrying a great deal of baggage in the form of histories of substance abuse; deficits in their educational, vocational, and ethical development; and disconnectedness to the mores and values of the larger community,” it reads. “Given the time and resources dedicated to corrections, it is absolute folly in social policy not to seek to address these deficit areas that inmates have brought to their incarceration.”

And address them he has, through programs that have won recognition nationally, but, more importantly, have succeeded in bringing down the inmate count by reducing the number of repeat offenders.

Sentence Structure

As he talked about these programs, Ashe began by offering a profile of his inmates, one of the few things that hasn’t changed much in 40 years.

“Roughly 90% come there with drug or alcohol problems,” he explained. “You’re looking at a seventh-grade education, on average; 93% of them lack any kind of marketable skill; and 70% of the people are unemployed at the point of arrest.

“Everyone knows that, in the state of Massachusetts, no one just happens to end up in jail — they land there after a long period of what I call irresponsible behavior,” he went on, adding that, likewise, no one just happens to correct that behavior and rehabilitate themselves.

Instead, that comes about by addressing those gaps he mentioned, or doing something about addiction, the lack of an education, the shortage of marketable skills, and the absence of a job.

In a nutshell, this is what the sum of the programs Ashe and his staff have created — both inside and outside the prison walls — is all about.

“What I’m most proud of, I think, is that we never waved at those gaps,” he told BusinessWest. “We put together strategies to deal with these issues.”

And as he likes to say — in those principles, or to anyone who will listen — re-entry to society begins on the first day of incarceration.

That’s when an extensive, seven- to 10-day orientation program and testing period begins, one designed, as Ashe said, to let staff “get to know the inmate — let’s find out who this guy is.”

Such steps are important, he went on, because even amid all those common denominators concerning education, addiction, and lack of job skills, there is still plenty of room for individualization when it comes to correctional programs.

Orientation is then followed by a mandatory transitional program, during which the sheriff says he’s trying he capture the inmate’s heart and mind. Far more times than not, he does, although sometimes it’s a struggle.

And as he said, the work has to begin immediately.

“I didn’t want them to languish,” he explained. “In years past, we would have programs, but they would have a beginning and an end, so you had waiting lists; to get into the GED program would take three weeks, to get into anger management would take four weeks, and I didn’t want that.

“If they come in and just languish in a cell for four, five, or six weeks, I’ve lost them,” he went on. “The subculture wins out — the inmates take over.”

There are always those reluctant to enter the mandatory transition program, the sheriff noted, adding that these individuals are sent to what’s known as the ‘accountability pod,’ a sterile environment where there are fewer rights and privileges. In far more cases than not, time spent there produces the desired results.

“Inevitably, what happens is, at the end of two to four weeks, they say, ‘Sheriff, I get it,’” Ashe told BusinessWest. “They say, ‘this is a coerced program … mainstream me; I’ll go to your programs.’ Not all the time, but a lot of the time, inmates will look back and say, ‘Sheriff, I’m glad you forced me to go through this.’”

Elaborating, he said ‘this’ is the process of addressing the various forms of baggage identified in principle 2 — addiction, lack of education, and a lack of job skills. Initiatives to address them include intense, 28-day addiction-treatment programs; GED classes; an extensive vocational program featuring graphics, welding, carpentry, food service, and other trades; and more.

Many of those who take part in the culinary-arts program will then move on to work at the Olde Armory Grille, an example — one of many — of how the work that begins inside the walls can lead to a productive life when one moves outside those walls.

Indeed, roughly 80% of the women who work in various capacities at the grille — and statistics show women enter the county jail with even fewer marketable skills than men — are finding work in the hospitality sector upon release, said Ashe.

To find out how that specific program works, and how it exemplifies all the programs operated by the Sheriff’s Department, we talked to Alben and Bill.

Food for Thought

The grille, which opened its doors in 2009, is in many ways an embodiment of that line explaining principle 2 regarding change. Indeed, there was a good deal of apprehension about this initiative at first, the sheriff recalled, adding that those attitudes had to change before the facility could become reality.

Over the years, it has become one of the most visible examples of the Sheriff’s Department’s focus on providing inmates with a fresh start — and a popular lunch spot for the hundreds of employees at the tech park and the community college across Federal Street.

Sheriff Ashe with Maryann Alben, catering and dining room manager at the Olde Armory Grille.

The restaurant is designed to provide real work experience and training for participants returning from incarceration as they re-enter communities, said Alben, adding that it involves inmates from the Ludlow jail, the Western Mass. Regional Women’s Correctional Center in Chicopee, and the Western Mass. Correctional Alcohol Center. These are inmates in what is known as ‘pre-release,’ meaning they can leave the correctional facility and go out into the community and work.

When asked what the program provides for its participants, who have to survive a lengthy interview process to join the staff, Alben didn’t start by listing cooking, serving, making change, or pricing produce — although they are all part if the equation. Instead, she began with prerequisites for all of the above.

“Self-esteem is huge,” she said. “When most women come in here, they have slouched shoulders … many of them have never had a job before,” she explained, adding that this is reality even for individuals in their 40s or 50s. “You bring them in here, and you try to build them up. Some of them will catch on sooner than others; some of them worked in restaurants way back when.

“We help them understand how to work with customers and leave the jail behind them,” she went on, adding that inmates don’t often exercise their people skills inside the walls, but must hone those abilities if they’re going to make it in the real world.

And many do, she went on, adding that there are many employers within the broad restaurant community who are able and, more importantly, willing to take on such individuals.

In fact, roughly 87% of those who take part are eventually placed, usually in kitchen prep work, she said, a statistic that reflects both the need for good help and the quality of the program.

Bill hopes to be a part of the majority that uses the grille as an important stepping stone.

“This is the next step in getting back into the community 100%,” he explained. “Not only with getting up early with a job to go to five days a week, but in the way it prepares me mentally and fundamentally for the next step into the real world.”

Such comments explain why an inmate’s final days at the grille involve more emotions than one might expect.

Indeed, the end of one’s service means the beginning of a new and intriguing chapter, which translates into happiness tinged with a dose of apprehension. Meanwhile, there is some sadness that results from the end of friendships forged with customers who frequent the establishment. And there is also gratitude, usually in large quantities.

“We’re giving them a chance to prove themselves,” said Alben. “And when they leave here, most of all them will say, ‘thank you for believing in me.’”

If they could, they would say the same thing to Sheriff Ashe. He not only believed in them, he challenged them and held them accountable, a real departure from four decades ago and what could truly be called white-knuckle times.

No Holds Barred

When asked what he would miss most about being sheriff of Hampden County, Ashe paused for a moment to think back and reflect.

“I think I would have to say that it’s the challenges, embracing the challenges,” he said one last time. “I’ll miss the work of recognizing the problems that our society faces and trying to come up with solutions.”

That answer, maybe as much as anything that he’s done over the past 41 years and will do over the next 11 months, helps explain why Ashe will be remembered for much more than what happened at that National Guard Armory.

And why he’s truly a Difference Maker.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]

Guiding Principles of Best Correctional Policy

(As developed by the Hampden County Model, 1975-2013)

1. Within any correctional facility or operation, there must be an atmosphere and an ethos of respect for the full humanity and potential of any human being within that institution and an effort to maximize that potential. This is the first and overriding principle from which all other principles emanate, and without which no real corrections is possible.

2. Correctional facilities should seek to positively impact those in custody, and not be mere holding agents or human warehouses.

3. Those in custody should put in busy, full, and productive days, and should be challenged to pick up the tools and directions to build a law-abiding life.

4. Those in custody should begin their participation in positive and productive activities as soon as possible in their incarceration.

5. All efforts should be made to break down the traditional barriers between correctional security and correctional human services.

6. Productive and positive activities for those in custody should be understood to be investments in the future of the community.

7. Correctional institutions should be communities of lawfulness. There should be zero tolerance, overt or tacit, for any violence within the institution. Those in custody who assault others in custody should be prosecuted as if such actions took place in free society. Staff should be diligently trained and monitored in use of force that is necessary and non-excessive to maintain safety, security, order, and lawfulness.

8. The operational philosophy of positively impacting those in custody and respecting their full humanity must predominate at all levels of security.

9. Offenders should be directed toward understanding their full impact on victims and their community and should make restorative and reparative acts toward their victims and the community at large.

10. Offenders should be classified to the least level of security that is consistent with public safety and is merited by their own behavior.

11. There should be a continuum of gradual, supervised, and supported community re-entry for offenders.

12. Community partnerships should be cultivated and developed for offender re-entry success. These partnerships should include the criminal-justice and law-enforcement communities as part of a public-safety team.

13. Staff should be held accountable to be positive and productive.

14. All staff should be inspired, encouraged, and supervised to strive for excellence in their work.

15. A spirit of innovation should permeate the operation. This innovation should be data-informed, evidenced-based, and include process and outcome measures.

16. In-service training should be ongoing and mandatory for all employees.

17. There should be a medical program that links with public health agencies and public health doctors from the home neighborhoods and communities of those in custody and which takes a pro-active approach to finding and treating illness and disease in the custodial population.

18. Modern technological advances should be integrated into a correctional operation for optimal efficiency and effectiveness.

19. Any correctional facility, no matter what its locale, should seek to be involved in, and to involve, the local community, to welcome within its fences the positive elements of the community, and to be a positive participant and neighbor in community life. This reaching out should be both toward the community that hosts the facility and the communities from which those in custody come.

20. Balance is the key. A correctional operation should reach for the stars but be rooted in the firm ground of common sense.

His Legacy of Generosity, Inspirational Living Will Carry On

Mike Balise, September 2015

Kathleen Sullivan was doing fine, talking in calm, measured — you might even call them precise — tones about Mike Balise and his many forms of support for the Homer Street School, which she serves as principal, until…

Until the conversation turned to the events of last fall — specifically, Mike’s latest, but certainly not last, gesture regarding what has become known simply, and famously, as the ‘coat thing.’ That’s when the dam holding back the emotions broke.

And with very good reason.

To explain, one needs to go back two more Octobers. That’s when Mike first entered the Homer Street School as a celebrity reader with the Link to Libraries program. As he walked down the main hallway, he noticed a number of winter coats, department-store tags still on them, hung on hooks along one wall.

Upon asking what this was all about, he learned that many students’ families cannot afford winter coats, so the school has long been proactive in soliciting donations of coats and money to buy more. But need had traditionally exceeded supply, he was told.

According to Homer Street School lore, Mike then asked what he could do to help close the gap, and soon commissioned a check for $2,000 — much more than was requested.

A year later, and a few weeks after he was diagnosed with incurable stomach cancer, Mike was back at the school — to read and present another $2,000 check for coats. And last October, after already living longer than his doctors told him he probably would, he was back again, to read and do a lot more than cover another year of coats.

“He said to me, ‘I might not be here next year, but those kids will be here, and some of them will need coats, so I want to give the students at Homer Street School $2,000 for an additional five years,’” said Sullivan, her voice cracking before she had to stop for a minute and compose herself. “And later, he wrote me an e-mail a few days before he passed away to thank me for an inspirational message I had sent to him, and for allowing him to be part of something special here at the school.

“That’s the kind of person he was,” she went on. “He was always thinking of others and how he could help, even while battling cancer.”

The coat thing is one very literal example of how Mike’s generosity, his ability to make a difference, will live on long after his passing. There are many others, from the donation the Balise company made to the expansion of the Sister Caritas Cancer Center in Springfield, to his work supporting efforts to assist autistic children and their families (one of his daughters has autism).

Mike Balise began his relationship with Homer Street School as a celebrity reader with Link to Libraries; it soon evolved into much more.

Indeed, Mike made Community Resources for People with Autism, an affiliate of the Assoc. for Community Living, the primary beneficiary for those wishing to honor him following his death. Jan Doody, the recently retired executive director of the center, said it’s far too early to know how the funds received in Mike’s memory will be used, but she does know they will certainly advance the agency’s mission for years to come, and help fill recognized gaps in support for individuals with autism.

While effectively filling such gaps is certainly one reason to call Mike a Difference Maker, another was the inspiration he provided to those across the area through the courageous manner in which everyone says he fought cancer and the death sentence he was given.

Everyone, that is, except his brother, Jeb, who took a departure from the rhetoric that usually accompanies such a battle, and offered a different, quite profound take on what went down over the 15 months after Mike was diagnosed.

“What he did, and I think he did it better than most people in that situation, is that he didn’t really battle cancer,” Jeb explained. “What he did was focus on positive things, enjoying life, and making a difference.

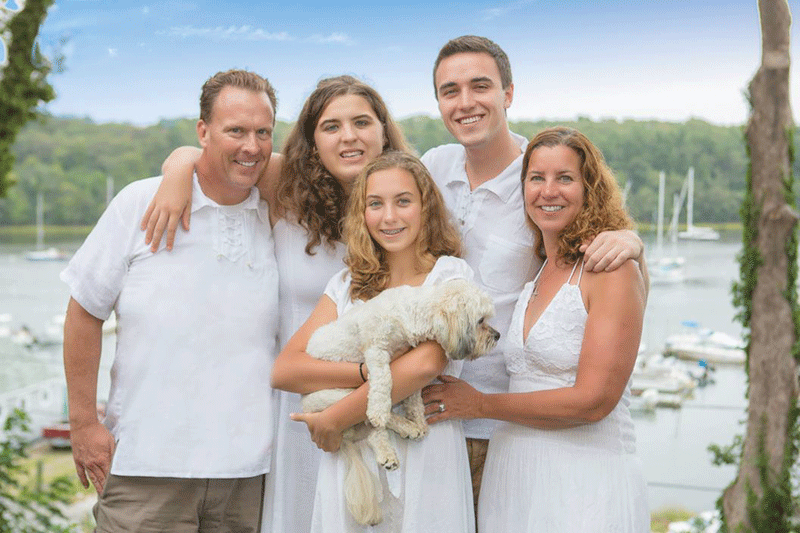

Jeb Balise says his brother, seen here with his family, didn’t battle cancer; rather, he fought to get the most out of every day.

“His battle was making sure that he got the most out of every moment, and not allow himself to fall into the trap of ‘how much longer do I have?’ and ‘I can’t do this anymore,’” he went on. “He had one very bad day, as I recall, but otherwise he did an amazing job of focusing on life, not his condition. And that’s what I mean when I say that he didn’t really fight cancer.”

By focusing on life, not only for those 15 months after his diagnosis, but for all 50 of his years, Mike Balise remains an inspiration to all those who knew him. For that reason, and for spending much of that time devoted to finding ways to help others, he was — and indeed always will be — a true Difference Maker.

Warm Feelings

Mike died early in the evening on Dec. 23, roughly a week after entering hospice care, and several days into Homer Street School’s two-week winter break.

Thus, the staff at the facility didn’t have a chance to collectively grieve until a meeting after school let out on Jan. 4, their first day back. It was an emotional session, said Sullivan, noting that there was literally not a dry eye in the room. People shared their thoughts on the many ways he supported the institution, she went on, and initiated talks on how best to honor him.

A statue of a man reading a book to children — a non-personalized model that Sullivan had seen on some Internet sites — was one early proposal, but the concept now gaining serious traction is a plan to name the school’s library after him.

That would certainly be fitting, because although he actually read to students there only a few times, Homer Street, a nondescript school in the city’s Mason Square neighborhood that opened its doors in 1896, and is thus the city’s oldest elementary school, has become a kind of symbol of Mike’s work within the community.