Life’s Work

Bill Ward Has Spent His Career Focused on the Big Picture: Jobs

Bill Ward has a wide assortment of photographs adorning the walls and shelves of his office in downtown Springfield.

There’s one of him conferring with Sen. Edward Kennedy, for example, and also one that puts him in a group with, among others, Dick and Rick Hoyt, the father-son team famous for their exploits in marathons and triathlons. There are others featuring a host of local, state, and national political leaders, and even a framed copy of the story announcing him as one of the first winners of BusinessWest’s Difference Makers award.

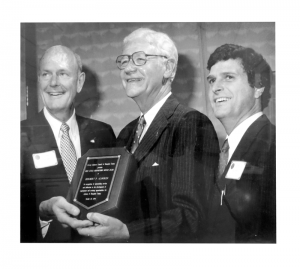

But maybe the one he’s most partial to shows him sharing the podium with Herb Almgren and Ben Jones. They were the first two chairmen of an organization called the Private Industry Council (PIC) — which would later become the Regional Employment Board of Hampden County — and individuals who would set a tone for the important work that Ward and those agencies would undertake.

It was Almgren, the long-time president of Shawmut Bank, who aggressively recruited Ward to be the first director of the PIC in 1981, later convinced Jones (who wasn’t even on the board at the time) to follow him as chair, and worked tirelessly to convince other business leaders of the need for workforce-development initiatives.

“He was very persuasive,” Ward recalled. “Thanks to him, people got the message that this was important work.”

And it was Jones, then-president of Monarch Life Insurance Co., who gave Ward a line he’s repeated dozens of times over the course of his career. “He was the first one to say to me that ‘a job is the best social program you can put in place,’” Ward recalled. “And he was certainly right about that.”

While Ward, who is “transitioning his career to its next phase” — that phrase has become his substitute for ‘retiring,’ because he said the latter is not at all accurate — is looking mostly ahead these days, and to what will come next, both for him and the region, he was compelled by BusinessWest to look back.

Indeed, as he prepares to leave the REB, probably by the end of the year if a successor has been chosen by then, he was asked to reflect on his career, the progress he’s seen in the broad realm of workforce development, the changes that have come to this region and its business community, and the many challenges looming for Greater Springfield — and his successor.

He started by going back to his days working at the Hampden County Skills Center, later known as the Mass. Career Development Institute (MCDI), where, for more than two years, he conducted extensive assessments of people who came to that organization seeking assistance and a path to a better life through gainful employment through training programs.

“I personally interviewed 2,000 low-income individuals, mostly women and adults, to gain perspective on their aspirations and goals,” he said, adding that some had been laid off from jobs, but many had never been in the workforce. “What I got from that was an incredible sense of the human potential in the city that was going to waste in part because people were not given the educational foundation or the training opportunities to make a better life for themselves and contribute to the workforce.”

And while reducing this wasted potential was never his official job description, it nonetheless became his career’s work. And he believes he can measure — in one way or another — what amounts to tangible progress.

Bill Ward, at right, is seen at an early annual meeting of the Private Industry Council with Herb Almgren, center, and Ben Jones.

“There’s been a really focused effort by the business community, and a level of collaboration has developed on how to address these workforce issues,” he went on. “What I see today is a better, stronger alignment in efforts to build a workforce; that’s been a major accomplishment.”

Hire Purpose

Before addressing a single question from BusinessWest, Ward spent probably half an hour reflecting on the words, deeds, and advice of Almgren, Jones, and many other individuals captured in the photos on his walls.

He did so to illustrate that what has been accomplished over the past three decades hasn’t resulted from the work of one man, but rather from the contributions of a wide array of individuals — from staff members to elected officials to volunteer board members.

Among the many anecdotes he offered was one concerning Jones a few months after he became chair of what was still the PIC.

“He was a very busy guy, and I remember going to his office one time to talk about a problem … like literacy within the community,” Ward recalled, noting that he didn’t remember the specific challenge in this case. “We talked for a long time, and finally he said to me, ‘Bill, from now on, if we’re going to meet for a half-hour, I want you to spend a maximum of eight to 10 minutes on the problem, and then I want you to spend the next 22 minutes on proposed or possible solutions, and what business can do about it.’

“That’s an interesting formula,” he went on. “And it impacted me. It forced me, in life going forward as I worked here, to look at a problem and say, ‘let’s get it defined quickly, and then let’s spend more time identifying solutions.’ That way, you don’t get into that ‘ain’t it awful’ game all the time.”

Ward said that story and many others help him explain how his career has been a series of personal and professional learning experiences that have made him a better administrator and helped him, his staff, his board, and supporters achieve positive results in many aspects of workforce development.

These range from a successful summer jobs program for young people to efforts to bolster adult basic education programs; from broad efforts to train workers for the region’s growing healthcare sector to programs aimed at having a pool of workers ready for the casino that will soon become part of the Western Mass. landscape.

And it all began very humbly, he recalled, adding that Almgren and others recognized the work he was doing at the Hampden County Skills Center and saw him as the potential leader of a new, federally funded initiative called the Private Industry Council, which involved the business community in efforts to help individuals become part of the workforce.

“He [Almgren] sensed that I was a willing learner,” said Ward. “I wanted to understand the dynamics between business people and the community at large. When you’re a willing learner, sometimes the teacher sees that potential and draws it out, and that’s what he did.”

The PIC started with a budget of $60,000, one full-time employee in Ward, and a part-time secretary. Today, the REB has 25 employees and a $15 million budget.

Ward credits both Almgren and especially Jones with giving the PIC, and then the REB, credibility in the community and something ultimately more important, access to business leaders who could drive change and progress.

“It was never said this way, but people felt that if Ben was involved with something, it was important work and things would get done,” he told BusinessWest. “And if he asked someone to come on the board, the response was almost always ‘yes.’”

Work — Force

Over the past 32 years, Ward said, the PIC and then the REB have achieved real progress in the broad realm of workforce development, with much of it coming in the form of answers to a nagging and somewhat perplexing problem that has dogged the region for most of his tenure — the so-called ‘skills gap.’

As the name suggests, this connotes the gap between the skills employers are demanding and those possessed by those seeking employment. In some ways, the gap is exaggerated by employers, but, by and large, it’s real, said Ward, adding that it is particularly acute in certain industry sectors, such as healthcare, precision manufacturing, and financial services.

And some of the REB’s most intriguing success stories have come in those sectors, where collaborative efforts involving industry players, academic institutions (especially the area’s community colleges and UMass Amherst), and REB officials have produced tangible results.

“We coined a phrase — we called it ‘sector strategy,’” Ward told BusinessWest. “What we’ve learned is that bringing these collaboratives together and getting agreement on a common mission and ways to identify progress is critical.”

Through such programs, said Ward, the REB and its various partners have succeeded in taking that word ‘collaboration’ out of the category of buzzword and making it something people can comprehend — and aspire to.

And one of the real challenges moving forward, he went on, is to make these collaborations between industry, higher education, and workforce-development groups more impactful.

“We need to touch more people and forge collaborations that create more and better jobs,” he explained, “so that, at least in several key industries, jobs will not go begging.”

Taking a big-picture perspective, Ward reiterated that perhaps the most significant and positive development during his tenure at the REB has simply been broad recognition of the fact that workforce development is, in fact, economic development.

While this may sound simple and logical, he went on, convincing legislative, business, and academic leaders of this hasn’t historically been easy.

And some of the most significant progress has come in efforts to engage the county’s two community colleges – Holyoke and Springfield Technical — in workforce-development efforts, he said, adding that, in many respects, this region is ahead of the rest of the state in this regard.

“Years ago, schools like this saw the workforce-development system as the stepchild,” he said, adding that, until recently, most community colleges were more focused on transferring students to four-year schools than preparing them for the workforce. “That’s all changed, and they see the other piece now, and there’s a huge alignment there.

“The first college that I know of to ever hire someone as the director of workforce development was Holyoke Community College,” he went on. “Years ago, these colleges thought of workforce development as something that limited their role, which they thought was to educate people and give them degrees. Now, they fully embrace their role in workforce development.”

Work in Progress

One of the challenges moving forward, he went on, is determining how to capitalize on this phenomenon to get the most responsive training programs for a host of industry sectors.

“Those leading the community colleges would be the first to say that their work is far from done, but there have been pockets of success,” he noted, adding that programs involving the wide spectrum of jobs in healthcare have, collectively, been the most visible and impactful initiative.

There will be plenty of other challenges for his successor and others involved in economic development when it comes to putting people to work, said Ward.

He put the economy at the top of that list, noting that, despite the best efforts of the REB and other agencies like it, unemployment will persist if employers lack the confidence and wherewithal to hire individuals — or if they persist in their desire to search for what has come to be known as a ‘purple squirrel.’ That’s a metaphor used by HR recruiters to identify the unrealistic expectations of a client company for the type of employee they desire.

“I think the phrase was born in the IT industry,” said Ward, adding that it now crosses all sectors and is certainly a factor in why unemployment remains high. “There is no such thing as a purple squirrel, but you keep searching for one anyway. Sometimes employers want a perfect person, and if they think there’s one coming in the door tomorrow, they’ll wait, and wait, and wait.”

Technology is another challenge, he said. As it advances, jobs are sometimes threatened because companies can do more with less, meaning fewer workers. Still, businesses can’t be afraid of technology, he said, and must instead embrace it to allow themselves — and the region as a whole — to become more competitive.

And the casino that eventually comes to Western Mass. will obviously be a challenge as well, he said, noting that workers will have to be trained for that work — the community colleges have already put programs in place — and, in the meantime, existing employers must prepare themselves for what 2,000 to 3,000 new jobs will mean for the employment landscape.

As for his own employment status, Ward said he’s seen a number of business leaders he’s worked with over the years struggle with the concept of retirement, and these tribulations have become yet another learning experience.

And that’s why he uses the term ‘transition phase.’

Meanwhile, he doesn’t like ‘consulting’ or ‘consultant’ much, either, but those words approximate what he will do and become — most likely in the fields of education and workforce development.

He expects he’ll do some advising (the term he much prefers) perhaps 10 hours a week, while also doing some volunteer work and getting back to golf and especially tennis, two sports he once enjoyed but put aside, especially after knee-replacement surgery five years ago.

“I’m transitioning to a different style of work,” he said, adding that his preference would be project work and, more specifically, initiatives with a beginning and an end. “I’m certainly not ready to fully retire.”

Developing Story

Look closely at the photo of Ward, Almgren, and Jones, and you’ll see three people seemingly looking out together in the same direction.

That’s obviously a photographer they’re looking toward, but it might as well be the region’s future.

The three men, and countless others, many of them captured in other pictures in Ward’s office, came together over the past three decades and embraced his overriding philosophy that workforce development is economic development.

Or, as Jones so eloquently put it, ‘a job is the best social program you can put in place.’

Bill Ward spent a career proving him right.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]