Patient/Resident/Client Care Provider: Dr. Michael Willers

This Physician Always Has His Patient’s Interest at Heart

Dr. Michael Willers

Dani Fine Photography

Dr. Michael Willers calls it simply “the look.”

When asked to describe it, he said it was somewhat difficult to put into words. What certainly wasn’t is his opinion that generating this look may well be his favorite thing about his work as owner of the Children’s Heart Center of Western Massachusetts.

It comes when a young patient finally comes to the realization that he or she is there at the home on Northampton Street in Holyoke to receive medical care — and not just play on the rug with LEGOs or a stuffed animal.

“I’ll be talking to the parents and I’ll be talking to the kid … and then I get my stethoscope out, and I sit down on the floor with the kid with my stethoscope,” Willers explained. “And it dawns on the kid at that moment that this is not just hanging out on the floor at some friend’s house. There’s a stethoscope involved, and they’re in a doctor’s office … and the kid’s thinking, ‘wait a second … I may have been duped.’

“They have this really surprised look on their face,” he went on. “Then I say, ‘it’s all good … we’re just going to have a listen, and maybe you want to listen, too.’ So we’ll listen to their heart together.”

Willers’ ability to prompt ‘the look’ doesn’t completely explain why he was chosen as the winner in the category of Patient/Resident/Client Care Provider, but it goes a long way toward getting that job done. He and his partners, Drs. Cyrus Yau and Meaghan Doherty, have created an environment that looks and feels far more like a home than a place where pediatric cardiologists would typically do their work.

And they run a practice where parents, often very anxious about bringing their child to a cardiologist to begin with, leave with all their questions answered and their fears, in most cases, anyway, put to rest.

Willers told BusinessWest that, unlike most healthcare operations today, this is not a volume business — or, to be more precise, not a business consumed with volume. Indeed, the three physicians generally book only seven appointments a day and spend an hour, on average, with each patient and their parents.

Taking care of kids and being with them … I could do that all day long and not get tired of it. It picks me up every time.”

And while his work is cardiology, Willers says he and his partners regard themselves as experts in stress reduction, especially when it comes to the parents of the children they see.

“I’ll often tell people that we specialize here in anxiety and worry,” he explained. “Our specialty is helping parents who are anxious or worried or scared. We take pride in tuning into that and understanding where parents are coming from and helping to unravel that anxiety and figure out exactly where their anxiety lies.”

But it’s not simply how much time is spent with patients and their families, or all this work in stress reduction that sets Willers apart. It’s also how that time is spent, which, in his case, means getting down to the patient’s level — quite literally.

“When I went to medical school, I knew I was going to get into pediatrics,” he said while explaining how he chose this line of work, or it chose him, as many working in healthcare opt to phrase things. “I love the social aspect of it, to be honest with you. There’s nothing like walking into an exam room and having a chance to get on the floor and play LEGOs with kids, talk to them about their lives and about what they enjoy.

“Pediatrics is intellectually interesting,” he went on. “But socially, it’s invigorating. The real reason I went into pediatrics as opposed to internal medicine or something else was purely social and emotional reasons. Taking care of kids and being with them … I could do that all day long and not get tired of it. It picks me up every time.”

The Pulse of His Practice

Willers isn’t sure of the exact date, but he believes that the home at 1754 Northampton St. in Holyoke is, like most of the others in that vicinity, not quite a century old.

It is large and comes complete with many nooks and crannies. For example, each of the examination rooms on the second floor has a short, narrow closet in one corner, the dimensions of which are determined by the structure’s sloping roof.

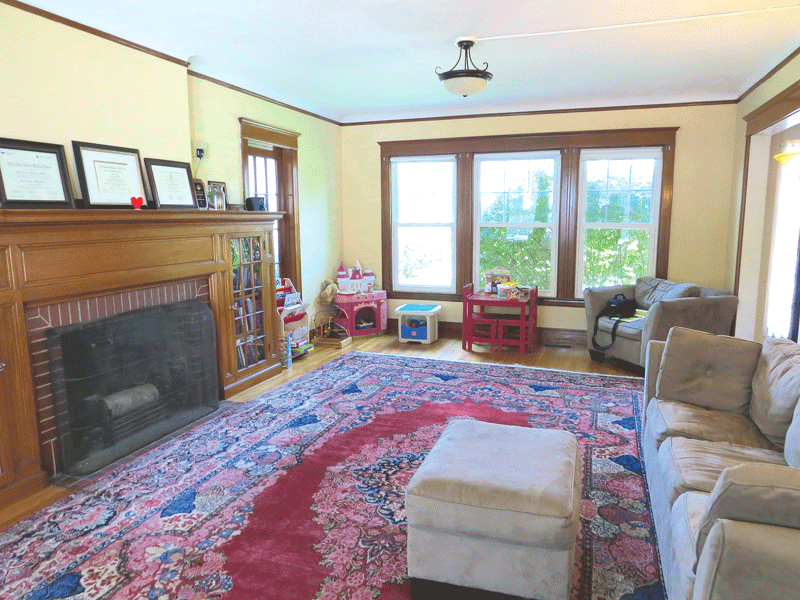

The waiting room at the Children’s Heart Center looks more like a living room, which is exactly what it was for roughly 90 years.

Each closet is filled with a trove of stuffed animals and toys, and on occasion, Willers won’t just go into the closet for something, he’ll actually emerge from it to greet a patient. To get his point across, he gave a demonstration.

“They’ll be looking for me to come in the front door, but once in a while I’ll get down in here,” said the 6-foot, 3-inch Willers as he squeezed in and closed the door behind him. “And then I’ll pop out like this and say, ‘hi, guys.’”

This demonstration, and the enthusiastic commentary that accompanied it, speak volumes about not what Willers does, but something at least equally important — how he does it.

Before we get into that in more depth, though, we need to first explain just how Willers arrived in that closet. It’s an intriguing story, and it really begins back at Wesleyan University, where he was finishing his work toward earning a degree in biology.

He wasn’t considering medicine at that time — he was leaning toward getting a Ph.D. in ecology or evolution — but a week spent with a group of internal-medicine residents at St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York changed all that.

“Six months before senior year, I decided I wanted to go to medical school,” he noted, adding that he enrolled at Dartmouth and, while working toward his degree, developed two passions — working with and for the underserved, and taking care of young people, for all those reasons mentioned above.

After completing his residency in pediatrics at Cornell Medical Center – New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Willers went to work at the Fair Haven Community Health Center in New Haven, Conn., an experience he described as the best of both worlds — taking care of an underserved, largely Spanish-speaking population, and also having teaching and hospital privileges at Yale-New Haven Hospital.

Desiring to narrow his focus to pediatric cardiology, he undertook a fellowship in that specialty at Yale School of Medicine, and upon completing it, he went to work at Baystate Children’s Hospital as a pediatric cardiologist, one of three on staff, while also serving as director of the Pediatric Exercise Physiology Laboratory.

Seeking to provide care in a different setting and in a different manner, he founded the Children’s Heart Center of Western Massachusetts in 2012.

“I wanted to be able to take care of people in a way that focused on patients as individuals, and their families,” he explained. “And spending time with them, answering questions, addressing their concerns, understanding their lives and how their heart problems impacted their lives, and how their lives impacted their heart issues.

“I wanted to do it in a way that wasn’t like a lot of hospital-based outpatient practices,” he went on. “There’s a lot of overhead with those facilities; you have to pay for the fancy waiting rooms, and you have to pay the CEOs and the vice presidents and the middle managers, and a lot of the money goes toward things not directly related to good patient care. And what that means is that the volume of patients you need to see in a hospital-based practice just to keep the boat floating is enormous, and that means spending less time with patients.”

He started in that home in Holyoke with an operating philosophy that minimized those overhead expenses and called for seeing seven patients a day for an hour each, as opposed to 30 patients a day for 15 minutes each.

When asked how this was doable in this modern age of healthcare, where volume is such a critical factor in a practice’s success, he paused for a moment before responding.

“It’s our priority,” he explained. “In any endeavor in life, if you prioritize the right things, then you can make it work. And we prioritize the relationships with patients and families. We don’t prioritize mahogany desks, and we don’t prioritize over-management.”

As the practice grew, thanks in no small part to a very receptive response from the region’s community of pediatricians, it expanded, both with additional cardiologists (Yau and Doherty) and with satellite offices in Amherst and Great Barrington.

Hardly a Murmur

As he offered a quick tour of the Holyoke office, Willers pointed out a number of design elements and choices regarding décor that were chosen specifically with the goal of making young patients and their parents feel comfortable and, well, at home.

These include the couches chosen over traditional plastic chairs seen in most physicians’ offices, oriental rugs, soft, padded examination tables, toys and games seemingly in every room, and patients’ exploits in coloring between the lines decorating one full wall at the front entrance.

Even the terminology reflects this operational philosophy, if you will.

Indeed, upon arrival, visitors are asked to sit in the ‘living room,’ not the ‘waiting room,’ because while the latter phrase effectively describes its official function, it certainly looks more like the former — because, for roughly 90 years, that’s exactly what it was.

But the friendly, patient- and family-focused tone of this practice goes well behind furniture and phraseology. It also involves everything from the considerable amount of time spent with a child and his or her parents, to the attention paid to the communication process.

To explain, Willers chose as his subject matter the heart murmur, a term that most parents don’t fully understand and one that usually generates far more fear and anxiety than are actually warranted.

So Willers said he starts off by focusing on the child, not the word ‘murmur,’ and moves on to making it clear to parents that, in the vast majority of cases, murmurs are normal and not life-altering.

Dr. Michael Willers says his favorite toy is whichever one his patient happens to be playing with at the time.

“I’ll tell a parent that there are seven different kinds of normal murmurs, and say, ‘let me tell you about the one your child has,’” he explained, adding that, for this exercise, he referenced the Still’s murmur, a common type of benign murmur named after the man who first described it, Dr. George Frederic Still. “And I’ll draw them a picture of a heart, explain what causes this murmur, and then tell them, ‘this is a totally normal murmur in completely normally healthy kids, something that develops around the age of 2 or 3 and lasts until the kid is 12 or 13 or 14. But it eventually goes away on its own and never turns into anything bad, and you never have to worry about it again.’”

Overall, Willers said he and his partners work hard to effectively communicate with patients and their parents to ensure they have a solid understanding of what’s happening with the heart in question.

“Some cardiologists will say, ‘your daughter has a heart-valve problem; she’s going to need a procedure on down the line — we’ll talk about it more later,’” he explained. “When we sit down with patients, our discussions are usually 20 or 30 minutes long; we draw pictures, we take notes, they go home — we intend for them to go home — with a really solid understanding of what’s going on with their kid, or with them if they’re an older person.

“In my experience, there’s nothing like uncertainty to breed anxiety, and there’s nothing like anxiety to disrupt the joy of parenting,” he went on. “And so we really try to get rid of the uncertainty and give people definitive answers in terms that are in plain English so that they can home with an understanding and a reassurance, and they don’t have to feel anxious.”

The Internet and all the information available on it has acted to fuel this anxiety, Willers said.

“They’ll hear something or read something on the Internet, and they’re really worried that their kid is going to die for X, Y, or Z reason, but they don’t really want to say it,” he went on. “So unless you can tune into their emotions and be on the same wavelength, you can’t really put their fears to rest.”

But getting on the same wavelength with parents is just part of this story. Getting there with children is what Willers probably enjoys most.

And while the methods for doing so vary with the age of the patient, the common threads are communicating and connecting.

“The first five minutes of every visit isn’t ‘so what brings you here today?’” he explained. “It’s ‘how’s your summer going?’ or ‘what was camp like?’ or ‘dude, how’s it going with your little sister?’ You spend five minutes connecting like that, and it brings a certain energy to that visit.”

A Different Beat

When asked if he had a personal favorite when it comes to kids’ toys and games — remember, he gets right down on the rug to play alongside his patients — Willers gave an answer that neatly sums up how this practice operates, and why.

“Whatever the kid is playing with at that given moment — that’s my favorite,” he told BusinessWest.

Such an attitude explains not only why Willers was chosen to be a hero in the Patient/Resident/Client Care Provider category, but also why he loves to create ‘the look’ and can’t wait to see it again.

Like he said, he can do this all day, and it picks him up every time.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]