Profiles in Business

He’s in the Business of Making “Entertaining Art”

Kevin Rhodes was on a tight schedule, but then … he usually is.On the day he managed to squeeze in some time for BusinessWest, Rhodes, the long-time music director of the Springfield Symphony Orchestra, had a lot on his plate, including everything from rehearsals to auditions for ‘first oboe.’

He was actually on break from the latter when he sat down for an interview in a tiny room off the box office at Symphony Hall, a site chosen to ensure that those vying for a job with the SSO would have complete quiet for their tryouts.

Candidate review — and the ultimate selections — in such searches are made by committee, Rhodes explained, adding that he is among several, including others in the orchestra who will play alongside the first oboe, who will listen to the hopefuls as they perform behind a curtain, so that the music — and only the music — is under consideration.

“These are completely anonymous … we’re careful not to use any gender-specific pronouns — people will just say ‘candidate No. 5,’ or ‘the next candidate,” Rhodes explained, adding that the work of assessing hopefuls’ abilities to play music and perform as part of the SSO is a very subjective exercise, a blend of art, science, and entertainment.

Which makes it much like the profession of orchestral conducting itself.

“People ask me if what I do is art or entertainment,” Rhodes, now wrapping up his 10th season with the SSO, explained. “I like to tell them that I try to make it entertaining art.”

There is much more to the job description, of course, he went on, adding that, to one degree or another, conductors must be musicians, marketers, and, in many ways, promoters of the arts, and especially music, in the communities in which they work. Rhodes has woven all three into his tenure with the SSO, and is credited by many with bringing heightened energy and a greater sense of awareness to the 67-year-old orchestra.

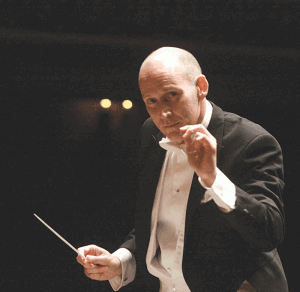

Meanwhile, he has become the face of the SSO — his image is used in most all of the orchestra’s marketing materials — and a fixture in the community, performing, guest lecturing, and teaching classes such as the one at the Community Music School on how to listen to music.

“There are several different ways to listen,” he said, adding that he explains them over the course of four sessions that are part of the school’s adult education extension program. “You can let the sound wash over you, like you’re taking a wonderful bath in it. But there is a more ultimately rewarding way, if one has just has a few tools to do that.

“It’s called ‘active listening,’ where while you’re listening to it, you’re sort of sorting through what’s coming at you,” he continued, gesturing with his hands in motions not unlike conducting, while noting that it would take several hours to explain exactly how one does such sorting.

For this, the latest in its ongoing series of profiles, BusinessWest did some active listening, and learning, as Rhodes discussed everything from his batons and how he needs to find another supplier — “I’m actually running low on them” — to how he’s reducing that tight schedule, or “calming the rhythm down,” as he put it,” in some respects, but still racking up the frequent-flyer miles.

Achievements of Note

On the day he spoke with BusinessWest, Rhodes was without his watch.

“I hardly ever forget it, but today I did, and I feel quite naked without it” he said, adding that, unlike those who rely on their cell phone for the time, he still looks at his wrist several dozen times a day.

And he needs to, given the schedule he keeps with just his two main professional assignments — as music director with the SSO and also with the Traverse Symphony Orchestra in Michigan. Consider this rundown of one recent stretch, which was, in most ways, quite typical.

“Three weeks ago, we had a big concert here with a huge reception after for my new contract signing,” he started. “The next two days were full of auditions, and the two after that were huge youth concerts, with thousands of kids. I then flew to Michigan, and the next day had a full day of meetings, a radio interview and a preview party for the upcoming season. The following days were filled with rehearsals with chorus and orchestra for Braham’s Requiem, then the performances and receptions. I did a radio commercial on Monday, flew home Monday night, and taught my class in listening to music on Tuesday.”

And while he’s forever looking at his watch, Rhodes also spends considerable time adjusting it for the time zone he happens to be in — or is flying toward.

Indeed, since leaving a host of concurrent assignments in Europe for his position with the SSO in 2001, Rhodes has crossed the Atlantic countless times for guest-conducting work at such venues as the Paris Opera, La Scala in Milan, the Verona Opera, and the Dutch National Ballet, among others. And in recent years, his plane rides have been longer; he toured Australia with the Paris Ballet in 2009, and last fall, he joined the Dutch National Ballet on tour in China.

Such locations, and assignments, are literally worlds away from Evansville, Ind., where Rhodes was born, spent many days (and also nights and early mornings) at his parents’ 24-hour “trucker diner,” and developed his passion for music.

“When I was in kindergarten, I was totally taken with the teacher playing the piano, so I started bugging my parents for lessons,” he said, adding that his family secured a piano from the same man who serviced the juke boxes at the family’s diner. “I found a young teacher — I think she was 16 when I started with her — and started playing in the school choir when I was 11.

“This led to playing for community theater when I was 13, and conducting for community theater when I was in high school,” he continued. “And by that time, it was pretty clear what I wanted to do.”

He received a bachelor’s degree in Piano Performance from Michigan State University, and later a master’s in Orchestral Conducting at the University of Illinois. He then served as music director of the Albuquerque Civic Light Opera, while also teaching piano at the University of New Mexico, before relocating to Switzerland in 1991.

His professional career unfolded in Europe, where he led many different orchestras, including the Vienna State Opera Orchestra (the Vienna Philharmonic), the Berlin Staatskapple, the Zagreb Philharmonic, the Dusseldorf Symphony, the Duisburg Philharmonic, the Swiss Chamber Philharmonic, the Symphony Orchestra of Madrid, the Basel Symphony Orchestra, and many others.

By 2001, he said, he and his wife made a conscious decision to return to the United States, and thus began what he called a quiet search for job opportunities. This can be a lengthy, laborious process, he continued, adding that positions like the one that opened in Springfield are filled at a “glacial pace.”

Citing the factors that brought him to Symphony Hall, he said geography played a small part — “Springfield is a perfect springboard to Europe” — but the institution and what people told him about it weighed much more heavily.

“I made some calls to people I knew in the Northeast,” he said. “They all raved about it, I applied, and it all worked out.”

Sound Strategy

As he talked about his work and job description, Rhodes returned to those words ‘art’ and ‘entertainment.’ They are both integral to what he does as music director.

But there is much more to it than that, he said, adding that he considers work to promote the orchestra, music, and the arts in general, to be a big part of his assignment.

And it’s a part he enjoys and feels quite comfortable doing.

“I seem to have an outgoing personality and I like people,” he explained. “I like meeting people and talking with people, and a love talking about music, so for me it’s an easy fit; I started going out in front of people at age 10 at kiddie talent shows, so I’m comfortable with the entertainment part of this and being the face of the orchestra.”

Rhodes said that not all conductors are as adept at, or comfortable with, the marketing aspects of this profession, and with larger orchestras those skills are certainly less necessary. But in markets like Springfield it’s what he called “a huge responsibility.”

And it takes many forms, from media interviews, to being highly visible in the community and doing what would be considered outreach work, to helping the public access and appreciate music.

“One of the messages I try to leave with people is that there’s so much that they can know about any piece of music that we play, but they can actually enjoy it without knowing any of that,” he explained. “It’s like listening to music — there are many ways to do it; you can listen to Beethoven knowing all about him, or you can listen to it, and enjoy it, thinking ‘that’s Beethoven, whoever that is.’

“I always try to make that point, because so often people think there’s no way they can enjoy it unless they know a whole ton about Beethoven,” he continued. “Once you get people over that fear, that concern factor, it’s amazing how it almost becomes a drug; they come more and more and they get more into it. It is infectious, and it’s great to see this curiosity inside of people that they didn’t know they had.”

Looking ahead, Rhodes, with that new contract signed, said his immediate career goals involve continuing the work he’s done in Springfield, Michigan, and elsewhere, specifically those efforts to introduce people across all social strata to music and essentially make them thirsty for more.

“I want to continue to expand our audience,” he explained, “but with the audience we have, which is very dedicated to us, I want to expand the concept of what is possible for them; I want them to expand their world and enable them to gain more from the experience of listening to what the orchestra plays.”

He’ll have plenty of opportunities to do that, because despite this talk of scaling back, schedule wise, he’s actually taking on more — at least on this side of the Atlantic.

In recent years, a typical schedule would look like the 2009-2010 slate, which included nine concerts in Springfield, six in Michigan, three productions with the Paris Ballet, or roughly 60 performances, two series of productions with the Dutch National Ballet in Amsterdam (another 30 performances), and a production at La Scala, with nine or 10 performances. And for this season, he took on the additional assignment of music director of the Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra in Cambridge, Mass., and four performances there.

To create some breathing room, he’ll pare the schedule in Europe slightly.

“There have been several occasions when I’ll be finishing the last performance in Europe on a Tuesday or Wednesday and get back either the night before, or even the day we begin rehearsals for a concert here,” he explained. “I’m calming it down from that.”

The Finale

As for those batons he uses … Rhodes said his supply came mostly via a “very colorful character” who hung around the Vienna State Opera in the 1990s.

“He had this music publishing and baton-making business, and it was all quite suspicious,” he said, choosing that last word carefully while noting that this was the middle man in the operation and the batons were actually made by someone else. “I am concerned, because I’m getting low on these, and I believe both of those characters are no longer with us.”

Finding a new supplier will be something else he’ll have to find room for in that schedule that soon will be lighter but still quite crowded — in between teaching people how to listen to music, assessing first oboe candidates, and, most importantly, making art entertaining.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]