From the Casino to Cannabis, Powerful Forces Have Changed the Landscape

By George O’Brien and Joseph Bednar

As the year and the decade come to a close, BusinessWest takes a look back at the stories that dominated the past 10 years and the forces that have in many ways changed the landscape — literally and metaphorically. These include everything from the tornado that touched down that June day in 2011 to the arrival of casino gambling in Western Mass.; from the emergence of a new and multi-faceted business sector — cannabis — to the growth and maturity of the entrepreneurship ecosystem. In short, the region looks a lot different than it did in January 2010, and most of it is for the better. Because this is 2020, here are the top 20 stories from the past decade.

The Casino Era

Perhaps the most dominant story of the decade was the introduction of casino gambling to the Common-wealth — and it covered the entire decade, to be sure, with a number of plots and subplots.

Perhaps the most dominant story of the decade was the introduction of casino gambling to the Common-wealth — and it covered the entire decade, to be sure, with a number of plots and subplots.

And, of course, the story continues.

Through the early part of the 2010s, the dominant story was where the casinos would be located. Legislation dictated that one of the resort casinos be located in what is considered ‘Western Mass.’ — everything west of Worcester — and a number of sites in several different communities emerged.

That list included the Big E grounds, the Wyckoff Country Club site in Holyoke, a location just off the Mass Pike entrance in Palmer, a site in Brimfield, and, of course, several locations in Springfield, including two downtown — one on the Peter Pan bus terminal site and the other in the tornado-ravaged South End — and one in East Springfield that eventually became home to CRRC (see listing below).

Eventually, MGM’s proposal to revitalize the South End with a $950 million resort casino was chosen by Springfield and then the Gaming Commission. Construction began in the spring of 2015, and for more than three years, the region watched the massive facility take shape.

It opened in August 2018, and since then, the focus has primarily been on revenues that are lagging well behind what was projected when the casino was proposed. However, Mike Mathis, president and COO of MGM Springfield, has maintained that casinos go through a “ramping-up” process that is generally three years or more in duration, and that the Springfield facility is still very much still in this ramping phase.

Looking forward, MGM officials are optimistic that sports gambling — still being considered by the Legislature — will provide a needed revenue boost. Meanwhile, they point to a number of positive developments spurred by the casino, including jobs, greater vibrancy in the downtown area, a trickle-down effect to other hospitality-related businesses, and new events, such as concerts and the upcoming Red Sox Winter Weekend.

Springfield’s Revitalization

When the decade began, Springfield was still climbing out of a very deep, very dark fiscal hole that it fell into several years earlier, one that took the city into receivership and made it the butt of jokes in the eastern part of the state.

When the decade began, Springfield was still climbing out of a very deep, very dark fiscal hole that it fell into several years earlier, one that took the city into receivership and made it the butt of jokes in the eastern part of the state.

As the decade ends, there is still considerable work to do, but Springfield is a very different place than it was 10 years ago. Its downtown, now anchored by a $960 million casino, is much more vibrant. CRRC is making subway cars in East Springfield. Union Station has been revitalized, and rail service has been expanded. The I-91 viaduct has been replaced. Many of the areas damaged by the tornado of 2011 have been revitalized. Tower Square has new ownership and some intriguing new tenants, including the YMCA of Greater Springfield.

Meanwhile, several of the parks, including Riverfront Park and Court Square, have been restored, and Pynchon Park, which links Dwight Street with the Quadrangle, is getting a facelift. Way Finders is building a new, $17 million headquarters building on the site of the old Peter Pan Bus Terminal. MassMutual is is spending $50 million to renovate and expand facilities in Springfield. Big Y recently completed a $46 million expansion. A $14 Educare facility just opened its doors. The list goes on.

There are still things to be done, such as revitalizing Court Square, building a replacement for the crumbling Civic Center Parking Garage, and spreading the vibrancy at MGM Springfield to properties across Main Street from that complex. But overall, Springfield is enjoying a resurgence, and has taken the step of announcing this loudly, and locally, in a marketing campaign created in concert with the Economic Development Council of Western Mass.

A city that was still very much in a dark place at the start of the decade has now come into the light.

The Rise of Cannabis

While many states have since followed suit, Massachusetts has long been near the vanguard when it comes to legalizing marijuana — first for medicinal purposes in 2012, then for recreational, or ‘adult,’ use in 2016. Both measures were passed by voters at the ballot box, and together they have created nothing less than another economic driver in Western Mass.

While many states have since followed suit, Massachusetts has long been near the vanguard when it comes to legalizing marijuana — first for medicinal purposes in 2012, then for recreational, or ‘adult,’ use in 2016. Both measures were passed by voters at the ballot box, and together they have created nothing less than another economic driver in Western Mass.

New England Treatment Access (NETA), the state’s first dispensary to begin adult sales, drew massive lines when it first opened in November 2018, but still maintains a healthy flow of customers as other shops, like Insa in Easthampton, Theory Wellness in Great Barrington, and others have begun recreational sales — with dozens more, in myriad communities, in various stages of permitting and development.

The burgeoning cannabis trade has impacted other fields as well, such as law, as firms have launched specialized practices to help entrepreneurs navigate the intricacies of this business. Meanwhile, banks eagerly await a possible move on the federal level to allow them to handle cannabis accounts.

Municipalities no doubt appreciate the additional tax revenue, which differs by town — in Northampton’s case, it’s 6% on top of the 17% tax customers pay the state, resulting in a $737,331 haul during NETA’s first three months of operation. In this light, it’s no surprise so many communities have embraced this new cannabis era in Massachusetts.

Marijuana remains illegal federally, but a surge of state-level legalization has probably gained too much momentum for that to remain the case forever. Massachusetts has played no small part in that trend.

A Decade-long Expansion

When the decade began, the economy, in many ways still recovering from what became known as the Great Recession, was nonetheless expanding.

And 10 years later … it is still expanding.

It’s been an historic run in many ways, and one that has seemingly defied the odds and host of issues — from trade wars to turmoil overseas to chaos on Capital Hill — to continue as it has.

For most of the decade, the expansion has been anything but profound — usually a percentage point or two or three of growth — but it has continued, bringing the stock market to new and sometimes dizzying heights — the Dow was above 28,000 as this issue went to press, and the S&P was nearing 3,200 — and the region and the nation to something approaching full employment.

These historically low unemployment levels have brought opportunities for workers and challenges for employers (see below), but they are the most obvious sign that the economy is still humming.

The question is … just how long can this last?

Many of the experts predicted a recession for sometime in 2019. It didn’t happen. Now, many are saying that one is likely for 2020, especially with the current inversion of the yield curve, whereby interest rates have flipped on U.S. Treasuries, with short-term bonds paying more than long-term bonds.

If history is any indicator, then this expansion seems destined to come an end soon. Then again, all the signs, from the stock market to the job market, seem to indicate otherwise.

Workforce Issues

As noted, the expansion has brought with it historically low unemployment in most regions of the country, including Western Mass.

And, as also noted, this has created a market heavily tipped toward the job seeker, which has meant challenging times for employers across virtually every sector of the economy.

Indeed, one consistent theme in the hundreds of interviews BusinessWest conducted with business owners and managers over the past decade has been the ongoing difficulty with finding and retaining good help.

It doesn’t matter which sector you’re talking about — healthcare, financial services, construction, distribution, retail, or hospitality — the one constant has been the struggle to fill the ranks.

At the start of the decade and maybe until a few years ago, employers would say it was a good problem to have; now, they don’t use that phrase so much. It’s just a problem.

And one that has led to some new terminology entering the lexicon: ‘ghosting,’ a situation that occurs when someone is slated to show up for work (or even an interview) and doesn’t, because something better has come along.

The situation has been exacerbated by forces ranging from the retirement of Baby Boomers to the arrival of MGM Springfield, and addressed by initiatives at the state and local levels — from agencies, community colleges, and organizations like Dress for Success — to give more people the skills they need to succeed in a technology-driven economy.

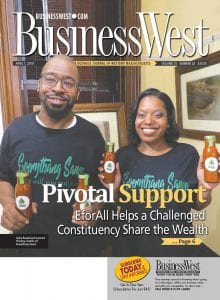

A Growing Entrepreneurship Ecosystem

One of the very best stories over the past decade has been the growth and maturation of the region’s entrepreneurship ecosystem, to the point where it is now a powerful force in the region when it comes to economic development.

One of the very best stories over the past decade has been the growth and maturation of the region’s entrepreneurship ecosystem, to the point where it is now a powerful force in the region when it comes to economic development.

The ecosystem has come to have a number of moving parts, from mentorship groups such as Valley Venture Mentors, EforAll Holyoke (formerly SPARK), and Launch 413 to entrepreneurship programs at area colleges and universities; from angel-investing groups that provide much-needed capital to initiatives like UMass Amherst’s Institute for Applied Life Sciences and Springfield-based TechSpring, which are working to take ideas from the lab to the marketplace.

Together, these moving parts have created large amounts of what could be called entrepreneurial energy, which has led to hundreds of new startups selling everything from cookies to mops to software programs that can enable machines to operate more efficiently.

Many of the entrepreneurs behind these ventures have made their way to the cover of BusinessWest, an indication of just how important the startup economy has become to the overall vitality of this region, and how large and impactful the entrepreneurship ecosystem has become.

While many are waiting and hoping for the next Google, Facebook, or Uber, most understand that the many smaller businesses now employing a handful of workers are already changing the landscape in individual communities, such as Holyoke and Springfield.

The Opioid Crisis

In 2016, when Gov. Charlie Baker signed into law a sweeping series of measures aimed at curbing opioid addiction, that class of drugs had long been recognized as a health crisis in the Commonwealth.

Specifically, it was the first law in the nation to limit an opioid prescription to a seven-day supply for first-time adult prescriptions and every prescription for minors, with certain exceptions. Among other provisions, information on opiate use and misuse must be disseminated at head-injury safety programs for high-school athletes, doctors must check the Prescription Monitoring Program database before writing a prescription for a Schedule 2 or Schedule 3 narcotic, and prescribers have ramped up continuing-education efforts, ranging from effective pain management to the risks of abuse and addiction associated with opioid medications, just to name a few.

Progress has been slow. In 2017, there were 1,913 drug-overdose deaths involving opioids in Massachusetts — a rate of 28.2 deaths per 100,000 persons, roughly double the national rate of 14.6. The greatest increase in opioid deaths was seen in cases involving synthetic opioids, mainly fentanyl: a rise from 67 deaths in 2012 to 1,649 deaths in 2017.

More recent news has been mixed. Opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts fell 6% in the first nine months of 2019 compared to the first nine months of 2018, according to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Between January and September of 2019, there were 1,460 confirmed and estimated opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts, compared to 1,559 in the first nine months of 2018.

However, the fentanyl problem grows — it was present in 93% of opioid-related overdose deaths where there was a toxicology screen over that time frame, up from 89% in 2018. Still, the state’s multi-pronged approach to the opioid epidemic may finally be making a difference.

The Tornado of 2011

There aren’t many residents and business owners who don’t have vivid recollections of the tornado that roared across Western Mass. on June 1, 2011.

There aren’t many residents and business owners who don’t have vivid recollections of the tornado that roared across Western Mass. on June 1, 2011.

Indeed, it traveled through a number of communities, leaving in its wake heavy damage and rebuilding challenges like the region had never seen.

It ravaged rural areas like Belchertown, but also traveled right down Main Street in Springfield, crossing over City Hall as it did so.

As it tore across Springfield and the region, the tornado didn’t discriminate; it damaged elementary schools, colleges, and especially what was then Cathedral High School, which was eventually razed and replaced with a much smaller facility known as Pope Francis High School. It laid waste to Monson’s scenic landscape. It changed the landscape at Veterans Golf Course in Springfield and completely uprooted Square One, the early-childhood education provider located in Springfield’s South End. (Joan Kagan, executive director of Square One, became the face of the disaster, literally and figuratively, as her picture — taken on Main Street with the agency’s ravaged home behind her — graced the cover of BusinessWest a few days later.)

After the dust settled, the difficult and inspiring cleanup and recovery began, and in some ways, it is still ongoing. Efforts to rehabilitate the South End of Springfield were greatly accelerated by MGM’s proposal to build a resort casino partly on parcels damaged by the casino. But several other businesses have risen in that era, including a new CVS pharmacy.

The Potential of Rail

State Sen. Eric Lesser has long been touting east-west rail service connecting Western Mass. and Boston, arguing that an 80-minute ride from Springfield’s Union Station to Boston’s South Station would be a game changer — and not only for Springfield.

State Sen. Eric Lesser has long been touting east-west rail service connecting Western Mass. and Boston, arguing that an 80-minute ride from Springfield’s Union Station to Boston’s South Station would be a game changer — and not only for Springfield.

“In Western Mass., we have great quality of life, great schools, a lot to offer, but we’re not creating jobs fast enough to keep people here,” he told BusinessWest. “As a result, we’ve seen a vacuuming of jobs and opportunities into a handful of zip codes. And in Boston, two crises are playing out simultaneously: out-of-control traffic gridlock and skyrocketing housing prices.”

Connecting the regions with high-speed rail could help solve both problems, he often argues. High-speed rail service between Pittsfield and Boston — with up to 16 round-trip trains running every day along the Interstate 90 corridor — was among the options for linking Western Mass. to Boston presented by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation to a state advisory committee in Springfield recently.

It’s not like rail hasn’t already made life easier in Western Mass., what with the launch of the Amtrak Vermonter line in 2016 and the Valley Flyer service between Greenfield and Springfield earlier this year. Ridership originating in Northampton on the Vermonter line increased from 17,197 riders in 2016 to 21,619 in 2018, reflecting a growing demand for rail.

“The new generation — people my age and younger — don’t want to sit in their cars all day,” Lesser said. “They don’t want long commutes on clogged highways. They’re open to using buses and trains in a way that maybe previous generations weren’t. Again, it would solve a lot of overlapping challenges we’re facing all at the same time.”

CRRC’s Rail Cars

A region that used to be home to many major manufacturing companies — at least, more than exist today — got a major boost in 2014 with the announcement that Chinese rail-car manufacturing giant CRRC was coming to Springfield to build hundreds of new cars for the MBTA’s Orange Line and Red Line systems.

The initial contract was for 152 Orange Line cars and 132 Red Line cars to replace aging trains. Two years later, an additional order was placed for 120 more Red Line cars, bringing the state’s total investment in new cars to $566 million.

From CRRC’s $95 million factory on Page Boulevard, which employs about 200 people, about a dozen trains have been delivered, and the company also built a 42,500-square-foot warehouse at the site this year to house large components.

The company’s leaders say they invested in Springfield with an eye on significant growth in the U.S. That has come to fruition, with a deal in 2016 to manufacture new subway cars for the city of Los Angeles and an agreement in 2017 to build new train cars for SEPTA, Philadelphia’s transit system, to name just two developments.

MBTA says the new vehicles incorporate improved safety features, wireless communications for monitoring potential maintenance needs, improved passenger comfort, new technology that provides important customer-facing information, and cutting-edge accessibility features, such as platform gap-mitigation devices.

For Springfield, however, the trains represent something greater — a major manufacturing success story at a time when one was needed.

The Dr. Seuss Museum

For years, people visiting the Dr. Seuss sculpture garden in the Quadrangle would ask where the museum devoted to the beloved children’s author and Springfield native was located. And they would be told there wasn’t one.

For years, people visiting the Dr. Seuss sculpture garden in the Quadrangle would ask where the museum devoted to the beloved children’s author and Springfield native was located. And they would be told there wasn’t one.

That all changed in the summer of 2017, with the opening of the Amazing World of Dr. Seuss Museum, a facility that has provided a true measure of the awesome power of the Seuss name and brand by attracting visitors from across the region and country and from around the world.

In its first year of operation, the museum enabled the Quadrangle to shatter attendance records, and the numbers have been steady and quite impressive since.

Museum officials are optimistic that the attendance and revenue boost from the Seuss facility will enable it to modernize and expand many of its other facilities. Meanwhile, civic and economic-development leaders say Seuss gives Springfield a powerful addition to its roster of attractions, one that can inspire — and lengthen — visits to the region.

Holyoke’s Renaissance

Another intriguing story from this past decade has been the resurgence in the city of Holyoke, a proud industrial city that has been re-inventing itself as a center for the arts, entrepreneurship, and, yes, cannabis.

In fact, in one interview with a TV crew several months ago, Holyoke’s mayor, Alex Morse, joked that it was goal, if not his mission, to see the community’s nickname change from the Paper City to the Rolling Paper City. That remark speaks to the enthusiastic manner in which the city embraced the legalization of cannabis in the Commonwealth and essentially opened its doors to many different kinds of businesses within that sector. Today, hundreds of thousands of square feet of former mill space is being eyed for cannabis cultivation and other uses, and several facilities are already operating.

But cannabis is only one of many good stories that have unfolded in Holyoke over the past decade. Others include the opening of the Massachusetts Green High Performance Computing Center in 2012; renovation of the property known as the Cubit Building, which is now home to apartments as well as the Holyoke Community College MGM Culinary Arts Institute; creation of SPARK, an agency devoted to encouraging and mentoring entrepreneurs (now named EforAll Holyoke); new rail service; and a burgeoning cultural district in the heart of downtown.

Like Springfield and other gateway cities and former industrial centers, Holyoke has evolved beyond those roots, and with very positive results.

Springfield Thunderbirds

One of the best stories of the decade involved hockey in Springfield, and specifically a new team that has infused the region with energy, imagination, and, yes, entertaining hockey.

One of the best stories of the decade involved hockey in Springfield, and specifically a new team that has infused the region with energy, imagination, and, yes, entertaining hockey.

We’re talking about the Springfield Thunderbirds, a team, and a story, so good that the franchise’s owners and managers were named BusinessWest’s Top Entrepreneurs for 2017.

To recap quickly, hockey, which has a rich history in Springfield dating back to the 1930s, was struggling in Springfield toward the middle of the decade. And then, it was gone, as the franchise known as the Springfield Falcons relocated to Arizona.

But a large group of entrepreneurs and community activists were determined not to see hockey relegated to the past. Their first move was to purchase a franchise in Portland, Maine, and relocate it to Springfield. Their second, even more important, move was to put Nate Costa, then working for the American Hockey League in its Springfield office, in charge.

His goal was to turn the Thunderbirds into a household name, and he has done just that, making the T-Birds, as they’re called, a big part of the renaissance taking place in Springfield.

The team is averaging more than 5,000 fans a night through a host of imaginative efforts — from promotions such as 3-2-1 Fridays ($3 beers, $2 hot dogs, and $1 sodas) to bringing in celebrities such as Red Sox stars David Ortiz and Pedro Martinez.

The end result? A ticket to a hockey game at the MassMutual Center is much more difficult to come by. That’s a sign of the T-Birds’ success on the ice, and in their ability to become part of the proverbial big picture when it comes to Springfield’s revitalization.

Bay Path University’s Evolution

A quarter-century ago, Bay Path College was a small, two-year school experiencing an identity crisis on a number of levels. Today, the institution is a university and a brand known across the region, and also across the country.

And the continued growth and emergence of Bay Path, led by President Carol Leary, who will be retiring next spring, certainly deserves to be among the biggest stories of the past decade.

The college, recently ranked among the fastest-growing private baccalaureate institutions in the nation, has, over the past several years, created the American Women’s College, an online institution; added several new programs, both at the undergraduate and graduate levels; opened a new science center in East Longmeadow; and become an industry leader in cybersecurity and computer-science programs. Meanwhile, it continues to stage its annual Women’s Leadership Conference each spring, an event that draws roughly 1,000 people to the MassMutual Center.

And in 2014, the institution had to create a new sign at its entrance in the center of Longmeadow, one with enough room for the word ‘university,’ a step that reflects its more global reach and its rising brand.

Over the past few years, Leary has been twice honored by BusinessWest, first with its Difference Makers award, and then its Women of Impact award. Those accolades speak to how much she has done for the school and within this region. But they also reflect just how far this school has come.

Ludlow Mills on Schedule

It’s been more than eight years since Westmass Area Development Corp. announced the 20-year project known as Ludlow Mills — a blend of both brownfield and greenfield development — and, about a third of the way through that time frame, progress at this complex of 60 buildings and adjoining undeveloped land has been steady.

When it started the clock back in 2011, Westmass said this project would generate $300 million in public and private investments, more than 2,000 jobs, and a more than $2 million increase in municipal property taxes. To date, high-profile initiatives on the site include the building of Encompass Health Rehabilitation Hospital of Western Massachusetts, WinnDevelopment’s overhaul of the structure known as Mill 10 into over-55 housing, and several smaller developments.

And there is more on the drawing board, most notably WinnDevelopment’s planned conversion of Mill 8, the so-called Clock Tower Building, into a mixed-used project featuring commercial space on the ground floor and more housing in the floors above.

The next key milestone for the project is the construction of Riverside Drive, which will open up approximately 60 acres of pre-permitted light-industrial property.

“We’re getting a lot of interest,” said Jeff Daley, Westmass’ new CEO, who noted that one of the front parcels was sold to the town of Ludlow for a new senior center, which recently broke ground. “That’s going to be a beautiful building to showcase the property from the eastern side.”

Ludlow’s municipal leaders say Ludlow Mills is already creating a trickle-down effect to the town and the region in terms of jobs and other benefits.

“It’s growing,” Daley added, “and there’s a lot of momentum, a lot of interest. People are coming in and creating stable businesses, and creating jobs. It’s really exciting.”

Ideas Take Shape at IALS

UMass Amherst may be renowned for cutting-edge scientific research, but when it comes from turning published papers into public benefits, the transition hasn’t always been smooth. Enter UMass Amherst’s Institute for Applied Life Sciences (IALS, pronounced ‘aisles’), where a collection of ‘core facilities’ is helping boost the state’s manufacturing economy — and innovation reputation — in myriad ways.

IALS was created in 2013 with $150 million in capital funding from the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center (MLSC) and the university itself. Its mission is to accelerate life-science research and advance collaboration with industry to effectively shorten the gap between scientific innovation and technological advancement.

The institute achieves this goal through three translational centers: the Models to Medicine Center, which harnesses campus research strengths in life science; the Center for Bioactive Delivery, which seeks to discover new paradigms for the discovery of optimized delivery vehicles for drugs; and the Center for Personalized Health Monitoring, which aims to accelerate the development and commercialization of low-cost, wearable, wireless sensor systems for health and biometric monitoring.

Located inside the IALS building, these core facilities — now numbering more than 30 — and their high-tech equipment are available not only to UMass researchers, but to companies that want to rent the space and equipment. For those companies, IALS provides a key resource they might not be able to afford on their own — and it could make a difference whether they invest in Western Mass. or go elsewhere.

Together, they form a pathway to commercialization — a vehicle to bring research to fruition and make an impact on society. By creating connections between research and the marketplace, IALS is doing its part to make Western Mass. a hub of innovation.

Baystate’s Expansion

Baystate Medical Center was already the region’s largest hospital — and the flagship of an ever-broadening network of hospitals and specialty practices — when it launched an ambitious, $295 million expansion, called ‘the Hospital of the Future,’ toward the end of the last decade.

‘Future,’ in this context, had multiple meanings. One was a forward-looking mindset when it came to technology, how a modern emergency room should look, and sustainable design and construction elements in the 640,000-square-foot addition. Another was the fact that Baystate left much of the new space undeveloped inside, knowing it would be needed in, well, the future.

When the new space opened in April 2012, its MassMutual Wing housed the Davis Family Heart and Vascular Center, which includes six surgical/endovascular suites designed to accommodate advanced lifesaving cardiovascular procedures, as well as 32 cardiovascular critical-care rooms that support state-of-the-art medicine. Later that year, a much larger Emergency Department opened in the new building, replacing an outdated ER that was designed to handle much less traffic than it was currently receiving.

That’s not the only way Baystate was expanding, of course. It also brought Wing Memorial Hospital and Noble Hospital into its system in 2014 and 2015, respectively, and continued adding to what has become a broad medical campus on the north end of Main Street in Springfield — not to mention its partnership with UMass Medical School in creating a downtown campus, which opened in 2016.

In short, whatever the future brings in healthcare locally, Baystate has placed itself square in the center of it.

Transformation in North Amherst

Cinda Jones, who, with her brother, Evan, represents the ninth generation of Cowls family landowners in North Amherst, has said each generation has transformed the land into what was most beneficial to the community at the time.

These days, she’s putting that philosophy to work at North Square at the Mill District. In fact, Jones’ company, W.D. Cowls Inc., and Boston-based Beacon Communities are developing three mixed-use buildings featuring 130 residential units — including 26 affordable units for people at or below 50% of the area’s median income — and 22,000 square feet of commercial space. The first residents began moving in over this past summer.

The partnership has benefited from local, state and federal support; in fact, it’s the first time that Amherst has taken advantage of legislation allowing the town to grant special tax incentives for projects that include affordable housing for low- and moderate-income tenants.

While impressive on its own, North Square reflects one of the more notable development trends in recent years: mixed-use structures in urban and village centers that generate economic vibrancy simply by putting more feet on the street.

Isenberg Climbs in the Rankings

One of the more intriguing stories from the past decade has been the steady rise of the Isenberg School of Management at UMass Amherst, a facility that has taken on a new profile — on campus and across the country.

One of the more intriguing stories from the past decade has been the steady rise of the Isenberg School of Management at UMass Amherst, a facility that has taken on a new profile — on campus and across the country.

The school, which first opened its doors in 1947, is now ranked first (actually, it’s tied with UConn) among the public undergraduate business programs in the Northeast in the 2020 U.S. News & World Report listings, 11th among the best public business schools in the country, and 50th in the rankings of the best business schools overall.

These numbers have been climbing steadily over the past years as the Isenberg School has made every greater investments in its programs and faculty, an expansion initiative punctuated by the opening this year of a $62 million expansion that puts a new face on Isenberg and boldly announces its intentions to continue its rise in the ranks.

EDC on a Mission

The goal of the Economic Development Council (EDC) of Western Mass. is multi-faceted, but has long boiled down to one core mission: encouraging the growth of the region’s economy, which was pounded by the Great Recession but has since been on a decidedly upward trajectory.

Its president, Rick Sullivan, says the EDC has seen a definite uptick in site searches, both from companies in the region that want to expand and those looking at Western Mass. for the first time.

“What we’ve become is what we call an ‘honest broker,’ he said. “We treat private developers and quasi-public developers the same. When a request comes in, it goes out to everyone on the list, all the economic-development professionals in the area, and we do not care whether the development occurs in Greenfield or Agawam or anywhere in between. We just want to have growth happen in the region, and that will continue to be the case.”

Many of the searches don’t result in a business moving here, he added, but those inquiries are a good gauge of the current health of the economy and the potential of the region, and they’re coming from a range of industries, from manufacturers and construction-materials companies to warehousing operations and call centers. When the region is doing well, Sullivan said, its natural pluses, such as its position near major interstates roughly between Boston and New York, become even more attractive.

Meanwhile, the EDC has forged stronger partnerships with colleges and universities, such as a cybersecurity management program at Bay Path and water-innovation and clean-energy work at UMass Amherst. “I think you’ll see the EDC do more with higher ed,” Sullivan said. “That’s where the talent pool is.”

The economy might eventually waver, but the EDC intends to maintain a steady course when it comes to raising the profile and success of its namesake region.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]

Joseph Bednar can be reached at [email protected]