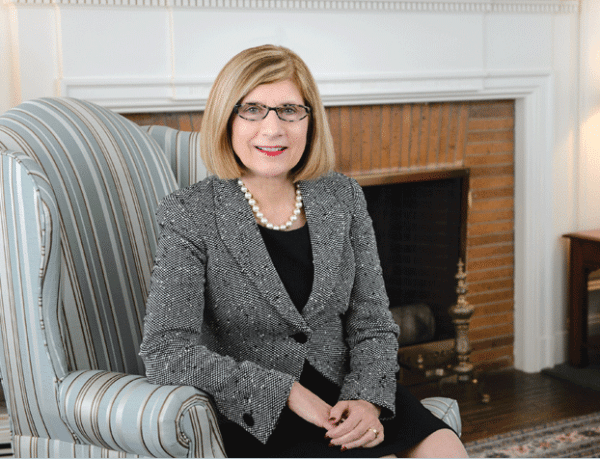

Carol Leary, President of Bay Path University

This Inspirational Leader Isn’t in the Community; She’s of the Community

Carol Leary, President of Bay Path University

Leah Martin Photography

Carol Leary says the executive search firms, the headhunters, don’t call very often any more. In fact, she can’t remember the last time one of them did.

She still gets e-mails gauging her interest in various positions, but they’re almost always of that variety that goes out to hundreds, if not thousands, of people. “Are you interested in, or would you care to nominate someone for, the job of president of ‘fill-in-blank college’” is how they usually start.

But not so long ago, Leary, who took the helm at Bay Path University in Longmeadow in late 1994, was getting calls all the time, most of them related to attractive opportunities within the broad realm of higher education. She declined to get into specifics, but said one of them was “very, very flattering.”

Still, it met with the same response as all the others — no response.

When asked why, Leary offered an answer that went on for some time. Paraphrasing that response, she said she was in a job — and in a community — that she was very committed to. And she had, and still has, no intention of leaving either one.

“Noel and I are not dazzled by big or prestigious; we’re dazzled by mission, vision, and making an impact,” said Leary, referring to her husband of 43 years. “We really love this community. We think you can make an impact here; you can make a difference.”

And the evidence that she has done just that is everywhere.

It is in every corner of the Longmeadow campus, starting with the brick sign at the front gate, which declares that this nearly 120-year-old institution, once known as a junior college, is now a university.

Carol Leary is where she always is — the middle of things — after a recent Bay Path commencement exercise.

It also exists in the many other communities where Bay Path now has a presence, including Springfield, where the school located its American Women’s College Online in a downtown office tower in 2013, and East Longmeadow, where it opened the $13.7 million Phillip H. Ryan Health Science Center a year ago.

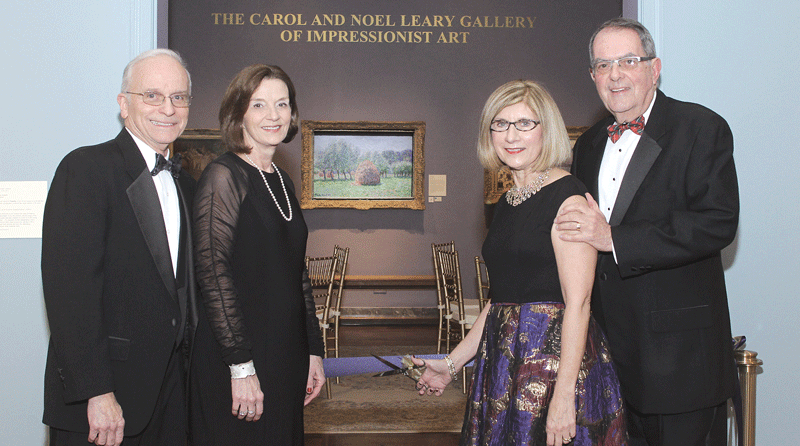

It’s also on the recently unveiled plaque at the D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts at the Quadrangle, the one that reads ‘The Carol and Noel Leary Gallery of Impressionist Art’ in recognition of their $300,000 contribution to that institution, which Noel has served as a board member for many years.

And, in a way, it’s in virtually every business and nonprofit in the region — or, to be more specific, any organization that has sent employees to the Women’s Professional Development Conference, which Leary initiated amid considerable skepticism (even at Bay Path) soon after her arrival.

When the conference was first conceptualized, organizers were hoping to draw 400 people; 800 turned out that first year. Today, the event attracts more than 2,000 attendees annually, and over the years it has welcomed keynoters ranging from Margaret Thatcher to Barbara Walters to Maya Angelou.

But Leary is best known for the turnaround story she is very much still writing at Bay Path, a school that was struggling and suffering from declining enrollment when she arrived.

Over the past two decades, she has led efforts that have taken that enrollment from just under 500 to more than 3,000 when all campuses and all programs, including online offerings, are considered. When she arrived, the school offered 14 associate degrees and three baccalaureate degrees; now, it offers 62 baccalaureate degrees and 20 graduate and post-graduate degrees.

In 2015, for the second year in row, the Chronicle of Higher Education included Bay Path on its list of the fastest-growing baccalaureate colleges in the country, and just a few months ago, Leary and Bay Path were ranked 25th in the 2015 ‘Top-100 Women-led Businesses in Massachusetts’ compilation sponsored by the Boston Globe and the Commonwealth Institute.

The sign at the main entrance explains just how far Bay Path has come under Carol Leary’s stewardship.

Such growth and acclaim didn’t come overnight or very easily, said Leary, who attributed the school’s success to vision, assembling a focused, driven team (much more on that later), and a responsive boards of trustees — all of which have facilitated effective execution of a number of strategic plans.

“Let’s see … there was Vision 2001, and 2006, and 2011, which we had to redo halfway through because of the crash, so there was 2013, and Vision 2016, which ends in June, and then we just launched Vision 2019,” she said, adding that she would like to be around for its end.

“I’ll do it only as long as my board wants me and the faculty and staff feel I can be effective as their leader,” she explained. “And as long as I can get up every day and say ‘wow, it’s great to go to work today.’”

She’s said that since day one, and it’s an attitude that only begins to explain why she’s a Difference Maker.

Making a Course Change

Leary told BusinessWest that, with few exceptions, all of them recently and schedule-related, she has interviewed the finalists for every position on campus, from provost to security guard, since the day she arrived on campus, succeeding Jeanette Wright, who passed away months earlier.

And there’s one question she asks everyone.

She wouldn’t divulge it (on the record, anyway) — “if I did, then someone might read this, and then they’d be prepared to answer it if they ever applied here” — but did say that it revealed something important about the individual sitting across the table.

“To me, that’s the most important part of any CEO’s job — the hiring of the individuals who will be working in the organization,” she explained. “Beyond the résumé and the skill set, I dig a little deeper. And my question tells me what that person cares about; it tells me what motivates them.”

The practice of interviewing every job finalist — but not her specific question of choice — was something Leary took with her from Simmons College, where she spent several years in various positions, including vice president for Administration and assistant to the president, the twin titles she held at the end of her tenure.

But that’s not all she borrowed from that Boston-based institution. Indeed, the Women’s Conference was based on an event Simmons started years earlier, and Leary has also patterned Bay Path’s growth formula on Simmons’ hard focus on diversity when it comes to degree programs.

She applied those lessons and others while undertaking a turnaround initiative at Bay Path that almost never happened — because Leary almost didn’t apply.

“I sent in my letter of interest and résumé on the last day applications were due,” she told BusinessWest, adding that she was encouraged to apply by others who thought she was ready and able to become president of a college — especially this one — but very much needed to be talked into doing so.

“I was nominated for this job — I wasn’t even looking for a presidency,” she went on, adding that, while she had her doctorate and “six years in the trenches,” as she called it, she wasn’t sure she was ready to lead a college. “I loved Simmons, I loved my job, I loved the mission, and I loved working in Boston; it was great.”

It was with all that love as a backdrop that she and Noel, while returning to Boston from a vacation in Niagara Falls that August, decided to swing through the Bay Path campus to get a look at and perhaps a feel for the institution. Suffice it to say they liked what they saw, heard, and could envision.

Indeed, what the two eventually found beyond the idyllic campus located in the heart of an affluent Springfield suburb was a college that possessed what Leary described using that time-honored phrase “good bones.”

And by that, she meant that it still had a sound reputation — years earlier, it was regarded as one of the top secretarial schools in the Northeast, if not the country — and, perhaps more importantly, a solid financial foundation upon which things could be built.

“I knew that Bay Path had been challenged with a decrease in its enrollment over several years,” she recalled. “But all the presidents had kept the institution financially strong; they kept deferred maintenance down, and the endowment was healthy for such a small school of 500 students. I looked at their programs, and I saw the challenges they were facing. But I looked at the balance sheet, and we both said, ‘we can see ourselves here; this has incredible potential as a women’s college.’”

When asked about those struggles with enrollment, Leary said they resulted in part from the fact that there was declining interest in women’s colleges, fueled in part by the fact that most every elite school in the country was by that time admitting women, giving them many more options. But it also stemmed from the fact that Bay Path simply wasn’t offering the products — meaning baccalaureate and graduate degrees — that women wanted, needed, and were going elsewhere to get.

So she set about changing that equation.

But first, she needed to assemble a team; draft a strategic plan for repositioning the school; achieve buy-in from several constituencies, but especially the board of trustees; effectively execute the plan; and then continually amend it as need and demand for products grew.

Spoiler alert (not really; this story is well known): she and those she eventually hired succeeded with all of the above.

To make a long story short, the college soon began adding degree programs in a number of fields, while also expanding geographically with new campuses in Sturbridge and Burlington, and technologically. It’s been a turnaround defined by the terms vision, teamwork, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

Milestones along the way include everything from the establishment of athletics (there are eight varsity sports now) to the first graduate-degree program (Communications and Information Management), launched in 2000, a year ahead of schedule; from the introduction of the innovative One-Day-a-Week Saturday College to those new campuses; from the launching of the American Women’s Online College to the school’s being granted status as a university in 2014.

Add it all up, and Leary and her staff have accomplished the mission she set when she arrived — to make Bay Path a destination.

That’s a great story, but the better one — and the reason why all those executive search firms were calling her — is the manner in which all this was accomplished.

Study in Relationship Building

And maybe no one can explain this better than Caron Hoban.

She didn’t work directly with Leary at Simmons — they were assigned to different campuses but served together on a few committees — but certainly knew of her. And when Leary went to Bay Path, Hoban decided to follow just a few months later.

“I knew her a little bit, and I was looking to make my next move just as she had been made president at Bay Path; they had a position open, and I applied for it,” said Hoban, who now holds the position of chief strategic officer.

When asked to summarize what Leary has accomplished at the school and attempt to put it all in perspective, Hoban obliged. But is doing so, she focused much more on how Leary orchestrated such a turnaround and, perhaps even more importantly, why.

And as she articulated these points, Hoban identified what she and others consider Leary’s greatest strengths — listening and forging partnerships.

“One of her greatest gifts is relationship building,” Hoban explained. “So when she came to Bay Path and the Greater Springfield area 21 years ago, she really committed to not just learning more about the college, but really understanding the whole region. She met with hundreds and hundreds of people and just listened.

“At my first meeting with her, she said, ‘what I’ve really been trying to do in my early days is listen to people and understand what the college needs and what the region needs,’” Hoban went on, adding that from this came the decision to create a women’s professional conference modeled on the one at Simmons, and a commitment to add graduate programs in several areas of study.

“She knew that the way to grow the campus and move from 500 students, which is what we had when she arrived, to the 3,000 we have now is by adding master’s-degree programs,” Hoban went on. “And these came about by her going out and listening to what the workforce needs were in the community.”

But Hoban said Leary’s listening and relationship-building talents extended to the campus community, the people she hired, and her own instincts, and this greatly facilitated what was, in every aspect of the word, a turnaround that was critical to the school’s very survival.

In 2007, President Leary welcomed poet, author, and civil-rights activist Maya Angelou to the Women’s Leadership Conference.

Indeed, in 1996, Leary recalled, she essentially asked the board for permission to spend $10 million of the $14 million the school had in the bank at the time over the next several years to hire faculty, add programs, and, in essence, take the school to the next level.

“I remember the conversations that were had around the table, and there was one member of the board, the chair of the academic committee, who said, ‘if we don’t do this, there might not be a future for Bay Path,’” she recalled. “I recommended that we make that investment — it had athletics in it, the Women’s Leadership Conference, and much more; that was Vision 2001.”

As it turned out, she didn’t have to spend all the money she asked for, because those degree programs added early on were so successful that revenues increased tremendously, to the point where the school didn’t have to take money out of the bank.

Looking back on what’s transpired at Bay Path, and also at the dynamics of administration in higher education, Leary said turning around a college as she and her team did is like turning around an aircraft carrier; in neither case does it happen quickly or easily.

In fact, she said it takes at least a full decade to blueprint and effectively execute a turnaround strategy, and that’s why relatively few colleges fully succeed with such initiatives — the president or chancellor doesn’t stay long enough to see the project to completion. And, inevitably, new leadership will in some ways alter the course and speed of a plan, if not create their own.

But Leary has given Bay Path not one decade, but two, and she’s needed all of that time to put the school on such lists as the Chronicle of Higher Education’s compilation of fastest-growing schools.

In keeping with her personality, Leary recoils when a question is asked with a tone focusing on what she has done. Indeed, she attributes the school’s progression to hiring the right people and then simply providing them with the tools and environment needed to flourish.

“I got up every day and knew I had to hire the best possible staff, people who believed in the mission,” she recalled. “And when people ask why Bay Path has been so successful, I say it’s because I hired the right people at the right time, and they just threw themselves into their jobs.”

While giving considerable credit to those she’s interviewed and hired over the years, Leary saved some for Noel and his willingness to share what she called “an equal-opportunity marriage.”

Elaborating, she said she agreed to uproot and follow him to Washington, D.C. and a job in commercial real estate there decades ago, and he more than reciprocated by first following her to Boston as she took a job at Simmons, then making another major adjustment — trying to serve his clients in the Hub from 100 miles away — when she came to Bay Path. He did that for more than a decade before retiring and taking on the role of supporting her various efforts.

“Noel has been a tremendous, tremendous support to me,” she explained. “He basically said, ‘this is an important job, I love what you’re doing, and I enjoy being a part of it.’”

And she implied that what he meant by ‘it’ was not simply her work at the campus on Longmeadow Street, but her efforts well outside it. They are so numerous and impactful that Hoban chose to say that Leary isn’t in the community, “she’s of the community.”

And perhaps the best example of that has been the women’s conference and how the region’s business community has embraced it.

Learning Curves

Dena Hall says it’s a good problem to have. Well … sort of.

There are more people at United Bank, which Hall serves as regional president, who want to go to the conference than the institution can effectively send.

Far more.

And that has led to some hand-wringing among those administrators (like Hall) whose job descriptions now include deciding who gets to go each spring and who doesn’t.

“We’ve gotten to the point where we have too many who want to go — we just can’t accommodate everyone, because we can’t have 50 current or emerging leaders out of the company at one time,” she explained. “So we’ve put it on each of our managers to identify one or two women in their business line who they believe should attend the conference and who will really benefit from what they see and hear.”

But these hard decisions comprise the only thing Hall doesn’t like about the women’s conference, except maybe finding a parking space that morning. That, too, has become a challenge, but, for the region as a whole, also a great problem to have.

Because that means that 2,000 women — and some men as well — are not only hearing the keynoters such as Walters, Angelou, and others, but networking and learning through a host of seminars and breakout sessions.

“You always learn something,” said Hall, who has been attending the conference for more than a dozen years. “Last year, I participated in the time-management workshop, and it changed the entire way I look at my schedule from Monday through Friday; the woman was fantastic.

“And there’s tons of networking,” she went on. “We use the conference here as a coaching and development tool for the more junior women on our team. There’s a lot of value in it, and for us, the fact that it’s five minutes away makes it so much easier than sending someone to Boston or New Haven or anywhere else.”

The conference is a college initiative — indeed, its primary goal beyond the desire to help educate and empower women is to give the school valuable exposure — but it is also a community endeavor, and one of many examples of how Leary is of, not just in, the community.

Others include everything from her service to the Colony Club — she was the first woman to chair its board — to her time on the boards of the Community Foundation, the Beveridge Foundation, WGBY, and United Bank, among others. She was also the honorary chair of Habitat for Humanity’s All Women build project in 2009.

And then, there was the support she and Noel gave to the museums and the current capital campaign called “Seuss & Springfield: Building a Better Quandrangle,” a gift that Springfield Museums President Kay Simpson described as not only generous, but a model to others who thought they might not be able to afford such philanthropy.

“One of the motivating factors for Carol and Noel,” she noted, “is that they wanted to demonstrate that, even if you don’t think you can make a substantial gift, with planning, you can do it.”

Leary said planning began years ago, and was inspired by a desire to preserve and expand a treasure that many in this area simply don’t appreciate for its quality.

“We really believe in the museum — we absolutely adore it,” she said. “I said to my niece and nephew at the gala [where the gift was announced], ‘this is your inheritance; you might be in the will, but there isn’t going to be any money in it — it’s going right here, so you can bring your children and your children’s children here decades from now.’

“Noel told the audience that night, ‘we have some big birthdays coming up, but forget Tiffany’s; we’re giving it to the museums,’” she went on. “That’s how much we think of this region; there are so many gems, like the museums, the symphony, CityStage, and others that need support.”

From left, Donald D’Amour, Michele D’Amour, Carol Leary, and Noel Leary at the ceremony marking the naming of the Gallery of Impressionist Art.

And looking back on her time here, she said it has been her mission not only to be involved in the community herself, but to get the college immersed in it as well. She considers these efforts successful and cites examples of involvement ranging from Habitat for Humanity to Big Brothers Big Sisters; from Link to Libraries to the college’s sponsorship of the recent Springfield Public Forum and partnerships that brought speakers such as Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor and author Wes Moore.

“You can’t be an ivory tower,” she told BusinessWest. “We have to be part and parcel of the good, the bad, and the ugly of any community.”

As she talked about the importance of involvement in this community, Leary made it a point to talk about the region itself, which she has chosen to call home. She said it has attributes and selling points that are easier for people not from the 413 area code to appreciate.

And this is something she would like to see change.

“People underrate this area, and the negativity has to stop,” she said with twinges of anger and urgency in her voice. “The language and the perception has to start changing from all of us who have a voice; we have to talk more positively.”

A Class Act

When asked how long she intended to stay at the helm at Bay Path, Leary didn’t give anything approaching a specific answer other than a reference to wanting to see how Vision 2019 shakes out.

Instead, she conveyed the sentiment that was implied in all those non-responses to inquiries from executive search firms: she’s not at all ready to leave this job or this community.

As she said, one can have an impact here. One can make a difference.

Not everyone does so, but she has, and in a number of ways.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]