From the Beginning, This Nonprofit Has Been a Neighborhood Enterprise

Gray House Executive Director Dena Calvanese.

The Gray House turns 30 this year.

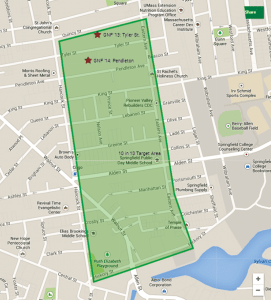

The specific anniversary date comes sometime in October, said Dena Calvanese, the long-time director of the facility (yes, a house painted gray) on Sheldon Street in Springfield’s North End, who admitted that she didn’t know it offhand.

Nor did she or Mike Walsh, chairman of the agency’s board of directors, know what the organization might do to mark the occasion, or when.

“There has been some talk, but nothing much, really,” said Walsh, adding quickly that, while this unique nonprofit agency is quite proud of its history and its heritage — there are several pictures of the founders and their early work to renovate the home covering one wall of the front hallway — there are far more pressing matters to attend to than planning round-number celebrations.

Indeed, the cold, harsh winter of 2013-14 is impacting many area residents — especially those living at or below the poverty line — and, therefore, several of the individual programs at the Gray House. And it is forcing the staff to be diligent and imaginative in crafting responses.

Indeed, the extreme cold has prompted a continuous run on warm clothing in the facility’s thrift shop. There, clients can fill a large plastic bag for the suggested contribution of $3 (if they have it), said Calvanese, adding that the agency has struggled to keep an adequate supply of coats, hats, gloves, mittens, sweaters, and sweatshirts.

“This is the emptiest I’ve ever seen our store,” she said, adding that, in addition to the cold, there have been many fires this winter that have left victims tasked with rebuilding wardrobes, and some home-heating allotments have been reduced. “We typically struggle to keep up with sorting our donations — we can’t sort fast enough because we get so much — but we’re really at a low this year.”

Meanwhile, in the facility’s food pantry, there’s a similar story.

Cuts to the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) that took effect last fall have left many families running out of food long before they run out of month.

“A family of four receiving food stamps was cut $36 a month,” said Calvanese. “For a lot of folks, that doesn’t sound like much, but $36 a month, when you’re shopping economically on a low-income budget, amounts to almost a full week’s worth of food; that’s a drastic reduction.”

The Gray House is responding to these developments with everything from urgent calls to its many community partners, including churches, colleges, and other nonprofits, for donations of warm clothing, to efforts to fill in some of what Calvanese called “nutritional gaps,” especially with regard to foods rich in protein, created by the cuts to the SNAP program.

These are examples of how the agency stays attuned to the many, and frequently changing, needs within the community, and adjusts, often on the fly.

Restoration of the old Victorian that became the Gray House, and the successful operation of the nonprofit agency that took that name, have both been community undertakings.

It has been this way since the mid-’80s, roughly two years after five members of the Sisters of St. Joseph — two of whom still live on the property — made the high bid of $500 for a run-down Victorian that had a tree growing through one of its 17 rooms.

What’s taken root in its place is a small but far-reaching nonprofit agency that started as what one founder called a “neighborhood enterprise” and has morphed into a regional phenomenon, one that epitomizes the phrase Difference Maker.

It does so with programs ranging from the food pantry and thrift shop — which serve 8,000 to 10,000 people each year — to community education programs involving hundreds of adults annually, to the Kids Club, which provides a host of after-school activities, most all of which come complete with learning opportunities.

These programs are run by the agency’s small staff, but they are made possible by a large army of volunteers, whose ranks include everything from college and high-school students to retired school teachers, as well as a number of partnerships with area schools and colleges, churches, and other nonprofits, and an active board of directors.

Together, these constituencies have helped the Gray House take its mission well beyond the North End, to all areas of Springfield and bordering communities.

As it recognizes the Gray House as a Difference Maker, BusinessWest takes a look back at how it all started, before returning quickly to the present to examine how this agency continues to carry out that broad mission.

Making Their Bid

Sr. Cathy Homrok described herself as the “realist,” and the woman sitting across the kitchen table from her, Sr. Jane Morrissey, as the “visionary.”

Those are the terms that have been consistently attached to these co-founders of the Gray House over the past 32 years or so as stories are recounted about how the property at 22 Sheldon St. was acquired, and how the nonprofit agency named after it came to be.

“She [Morrissey] just kept saying, ‘we should do something with that house,’” Homrok, who joined the Sisters of St. Joseph in 1959, recalled. “And I was the voice of reason. I kept saying things like, ‘what are we going to do with that house?’ ‘Where are we going to get the money?’ ‘We don’t know anything about renovating houses’ And ‘it’s a nice dream, but how can we do it?’”

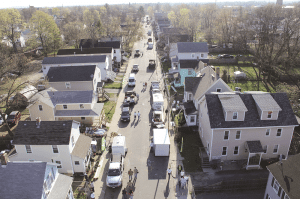

‘That house’ was, at the time, a 110-year-old Victorian that was at least mostly gray — Morrissey remembers it being two-toned — and had been abandoned since a fire broke out in 1976 in the second-floor apartment that she and Homrok now occupy. Morrissey used to walk by the home every day while she and other members of the Sisters of St. Joseph lived in an apartment building just a few hundred feet or so down Sheldon Street, and she had a good view of it out her bedroom window after they moved to Huntington Street, one block to the north.

Sr. Cathy Homrok, left, the ‘realist,’ and Sr. Jane Morrissey, the ‘visionary,’ are two of the founders of the Gray House, and still live on the second floor.

Discussions about doing something with the house eventually turned to opportunistic action. Most efforts at reflection are focused on the auction, which occurred one cold day in January 1982, but Morrissey, who joined the order in 1963, said the ball started rolling months before.

Indeed, she recalls that the six founders — there were three other Sisters of St. Joseph, Kathleen O’Connor, Joan Roche, and Eileen Witkop, as well as Julie James, a layperson — created the nonprofit agency The Gray House Inc. well before the auction. In fact, Morrissey had applied to the Community Foundation for a grant to rehabilitate the property and create programming before the group had assumed ownership.

They didn’t get the grant, but did get some sage advice from Robert Van Wart, director of the foundation.

“He told us we were overreaching in what we asked for, considering that it was a request from a nonprofit that was named after a house we didn’t own,” said Morrissey with a laugh, adding that this oversight, if it could be called that, was corrected at the auction.

She recalls that there were initially a number of bidders at the site that day, but the herd thinned considerably, and almost completely, when her brother, an attorney who was on hand to assist however he could, approached some of the rivals and informed them that they would be competing with a group of nuns bent on community activism.

“I think they were members of the legal community representing property owners,” Morrissey said of the rival bidders. “My brother said something to one of them, and that person said something to another person, and they all got in the cars and drove away; we were the only ones left.”

There’s a picture hanging in the front hallway that captures the moment just after the sisters prevailed at the auction. Several of the founders are beaming and rejoicing in their triumph. But in reality, they had a much more difficult fight ahead, because the house was in terrible condition, and resources to complete Morrissey’s dream were scarce.

But the project soon became what Homrok called a “neighborhood enterprise.” The owner of a nearby lumberyard who was also in the construction industry pledged both supplies and technical support. Meanwhile, Kathleen O’Connor’s father, also in construction, lent his assistance, as did others from across the North End of the city. A former colleague of the sisters from their years teaching at Elms College helped with fund-raising. Even neighborhood children pitched in and helped with painting and other tasks.

“It was great to see the community come together and help us get off the ground,” said Morrissey. “Sometimes, walking down Main Street, you’ll bump into someone who helped, and they’ll say, ‘remember me? I lived across the street from the Gray House.’”

As the work to rehab the Gray House went on, so, too did the task of finalizing a mission statement and creating programs.

“Having lived in that neighborhood, we knew well what the needs were — food, clothing, and education,” said Homrok, adding that, beyond those basic necessities, some people simply needed a place where they could find peace and support. The Gray House has become all that.

Life Lessons

Just as creating this sanctuary was a neighborhood, or community, enterprise, the task of carrying out its mission has become much the same thing, said all those who spoke with BusinessWest.

This became evident as the two sisters provided a quick tour of the first-floor operations on a busy Tuesday morning.

Indeed, there were several volunteers, most of them retired individuals, working with people of various ages and many different nationalities as part of the Gray House’s Community Education Support Program, otherwise known as CESP.

Under the direction of Glenn Yarnell, the program offers English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) services, basic skills (reading, writing, and math) tutoring, and English conversation classes.

Michael Walsh, chairman of the board at the Gray House, says the nonprofit has always been responsive to changing needs within the community.

There are 75 adult learners enrolled at any given time, said Calvanese, adding that the program has grown to include literacy development for resettled refugees, and has become an important addition to region-wide efforts to help individuals break through the barriers to employment and inclusion in the community.

“About 85% of our learners are doing English as a second language, but quite a few are doing English and literacy simultaneously,” she explained. “That’s because they grew up speaking another language, but didn’t have access to education in that language. So not only do they not know English, but they’ve never held a pencil before.”

Many of the participants are refugees, said Calvanese, listing Somalia, Burundi, Myanmar, and Iraq as just some of the countries of origin. Meanwhile, the adult leaders run the gamut, education-wise, with many having no formal schooling whatsoever, while others have advanced degrees but need to learn English.

Tutoring comes in one-to-one form or in small groups so people can learn at their own pace, she went on, adding that the ethnic and cultural diversity in the learning areas gives the Gray House a unique look and feel.

“It’s incredible to see the diversity we have and also have people be at peace with each other,” she said, adding that participants probably speak 20 different languages. “We may have people from two different African nations who were at war with one another not long ago. They come here, and they get along, and we have Muslims sitting beside Christians; it’s really beautiful to see the diversity at the house and have it be so peaceful.”

The Kids Club, meanwhile, provides after-school activities for two hours, Monday through Thursday, for students in grades 2 through 6, many of whom stay with the program for several years. There are 16 participants, signed up on a first-come, first-served basis, who have what amounts to a daily regimen carefully designed by the staff.

It starts with a snack and continues with 45 minutes for homework and other school-related work, with a heavy accent on reading, but also flash cards, creative writing, and educational games. There is then activity time, which always includes a learning component.

“Somers Academy donated some pumpkins for the kids to paint,” said Calvanese, providing an example of how it all works. “But before we let them paint them, we had them measure their circumference, height, and weight, and make charts to see which team had the biggest pumpkin. And then they got to paint.

“What we know about poverty is that a big reason why people end up in that state is a lack of education, so we really push that with our kids,” she went on. “And what we try to do with our activities is sneak in education in a fun way so they start to realize that learning can be fun.”

And while there is consistency to all programming at the Gray House, there is also much-needed flexibility, because the community is constantly evolving, said Calvanese, and so are its needs.

“Every time there are changes in the community, we try to adjust to meet them,” she told BusinessWest. “It never gets too stagnant around here, because as different populations come in, we’re adjusting.”

Home — Safe

Today, the Gray House, as reconstructed, is showing many signs of its age. The distinctive turret is deteriorating, said Calvanese. Meanwhile, the porch and chimney need help, and the flooring in the bathroom is in need of replacing.

Doing some quick math in her head, she said that maybe $75,000 worth of work is needed — and soon.

But like the 30th-anniversary celebration, these repairs and upkeep projects are going to have to wait, she told BusinessWest, because there are simply more important things to do with available time and resources.

The work will eventually have to be done, said Walsh, adding quickly that, while the facility’s board has thought about the high cost of operating in this rambling Victorian — and also about possibly moving someplace more modern and practical — those thoughts have been fleeting.

After all, the Gray House (or Casa Gris in Spanish) is more than a name on a nonprofit organization. It’s a place, a landmark, and a refuge of sorts in what remains, statistically, one of the poorest neighborhoods, if not the poorest, in the Commonwealth.

Returning to the subject of that 30th anniversary of the Gray House, Walsh said the agency actually just finished celebrating its 25th last fall.

“We don’t do big celebrations, just long ones,” he joked, noting that the organization had four of the surviving founders on hand for the dedication of a remembrance garden on the property, complete with a patio and bricks commissioned to honor founders and donors. It was three years in the making, he said, adding, again, that there is nothing yet in the works for the 30th, although something will probably come together. “We may try to do something appropriate in the fall, mostly to honor our founders and take a moment to reflect on what they’ve done.”

In the meantime, he and Calvanese said the very best way to celebrate is to simply find ways to do more to help a huge constituency in need.

That’s been the real mission since those sisters prevailed in that auction on Sheldon Street.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]