Expanding Their Vision

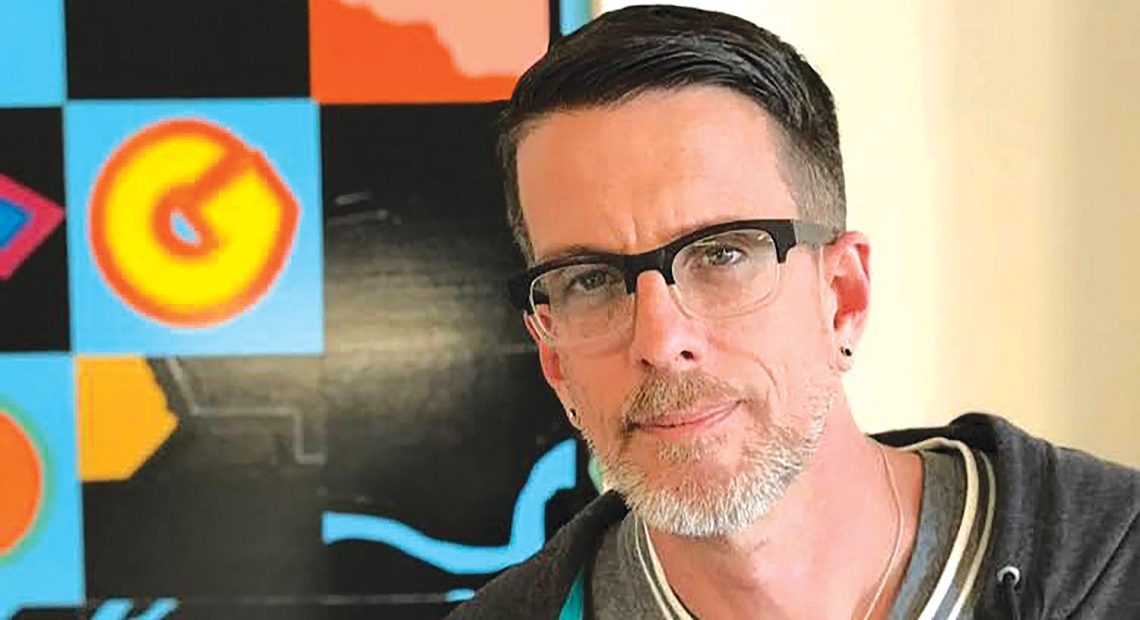

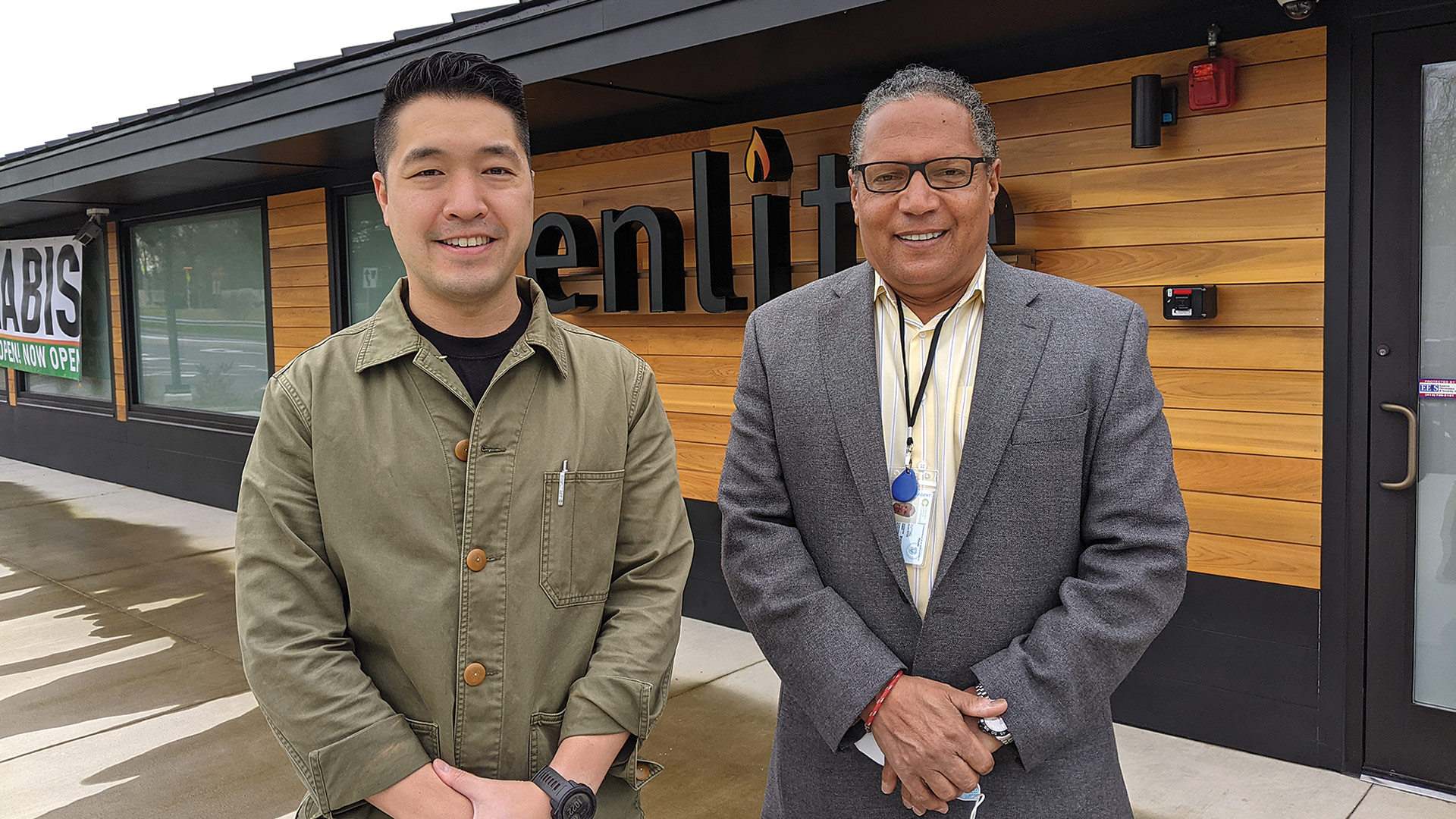

Co-owners Chris Vianello, Rich Rainone, and Keshawn Warner.

Photo by Savanna SLUSA Productions for Dazed Cannabis

Chris Vianello said he and his partners at Dazed Cannabis never intended to be the first player on the scene. In fact, their first dispensary in Holyoke, which opened in 2021, was that city’s fourth.

“We were never the only game in town. That’s not our model. If our only claim to fame is that we’re the only game in town, that’s not a sustainable business practice,” Vianello said, noting that Dazed instead stresses quality products and its friendly but funky vibe. “We anticipated competition going into this, especially because Holyoke is not a limited-license jurisdiction.”

The model has worked. Not only has the Holyoke shop has survived a raft of competition, but Dazed co-owners Vianello, Rich Rainone, and Keshawn Warner have opened two stores since then: in New York City in 2023 (first as a pop-up shop in April and then a permanent storefront in November) and, just last month, in Monson, where Dazed is currently the only cannabis game in town.

That store, where the Magic Lantern strip club operated for more than a half-century before closing in 2022, honors the location’s history by keeping a small stage and dancer’s pole as part of the décor.

Rainone told the Cannabis Business Times recently that the first 90 days after a dispensary’s opening are the most turbulent. The first month is all about establishing operating procedures and employee routines, the second about fixing the challenges of the first 30 days, and the third month about putting it all together and excelling.

He told the publication that Dazed is a “fun party brand,” with visitors encountering a “meet and greet” before they get to security, and the environment inside the shop characterized by music playing and a pink-dominated color scheme that extends to all three dispensaries.

When asked why the team chose each location, Vianello told BusinessWest they appeal in different ways.

“We were never the only game in town. That’s not our model. If our only claim to fame is that we’re the only game in town, that’s not a sustainable business practice.”

“You try to find the balance between what’s the ideal location and what’s a doable location,” he said. “We try to straddle that balance; we don’t want to open up a dispensary just anywhere because that’s not going to work, but also we don’t want to get stuck looking for the perfect location and end up not opening anything. They’re all different in where the traffic is coming from and how we attract different folks to different stores.”

At a time when competition is fierce and some stores have actually closed in Massachusetts, Dazed’s focus on customer experience and steady growth has been a winner, he added.

“In 2018, 2019, you had people who were the only game in town. And that worked for those who were able to get themselves positioned to be the first in the market. They had months, even years where they were cranking as literally the only game in town.”

“We never experienced that. We were never the first,” he continued, understanding that being the first shop in Monson is still being one of nearly 400 in Massachusetts. And amid increasing competition, Vianello doesn’t intend to engage in a race to the bottom when it comes to pricing.

“We’ve seen people trying to undercut the next guy by 10 cents and create an environment where you devalue the purpose of even being there,” he explained. “Understanding that price is always part of what people consider when shopping, you still have to differentiate yourself; you have to make yourself stand out. Ideally, you want people that are coming to you rather than other people because they like what you have going on.”

By doing so, he said, “we’re creating our own lane, our own pie, instead of slicing up what’s already out there.”

Rolling with the Punches

And there is, indeed, a lot out there, and still considerable debate over whether the burgeoning cannabis industry has a ceiling or whether there’s enough growth potential — from new users or consumers rejecting the illegal market to buy from regulated stores — to make up for more competition emerging from both within the Bay State and from outside its borders.

“A lot of it comes down to community outreach, giving people the information they need to buy legal rather than what they’ve been doing the last 20 years,” Vianello said.

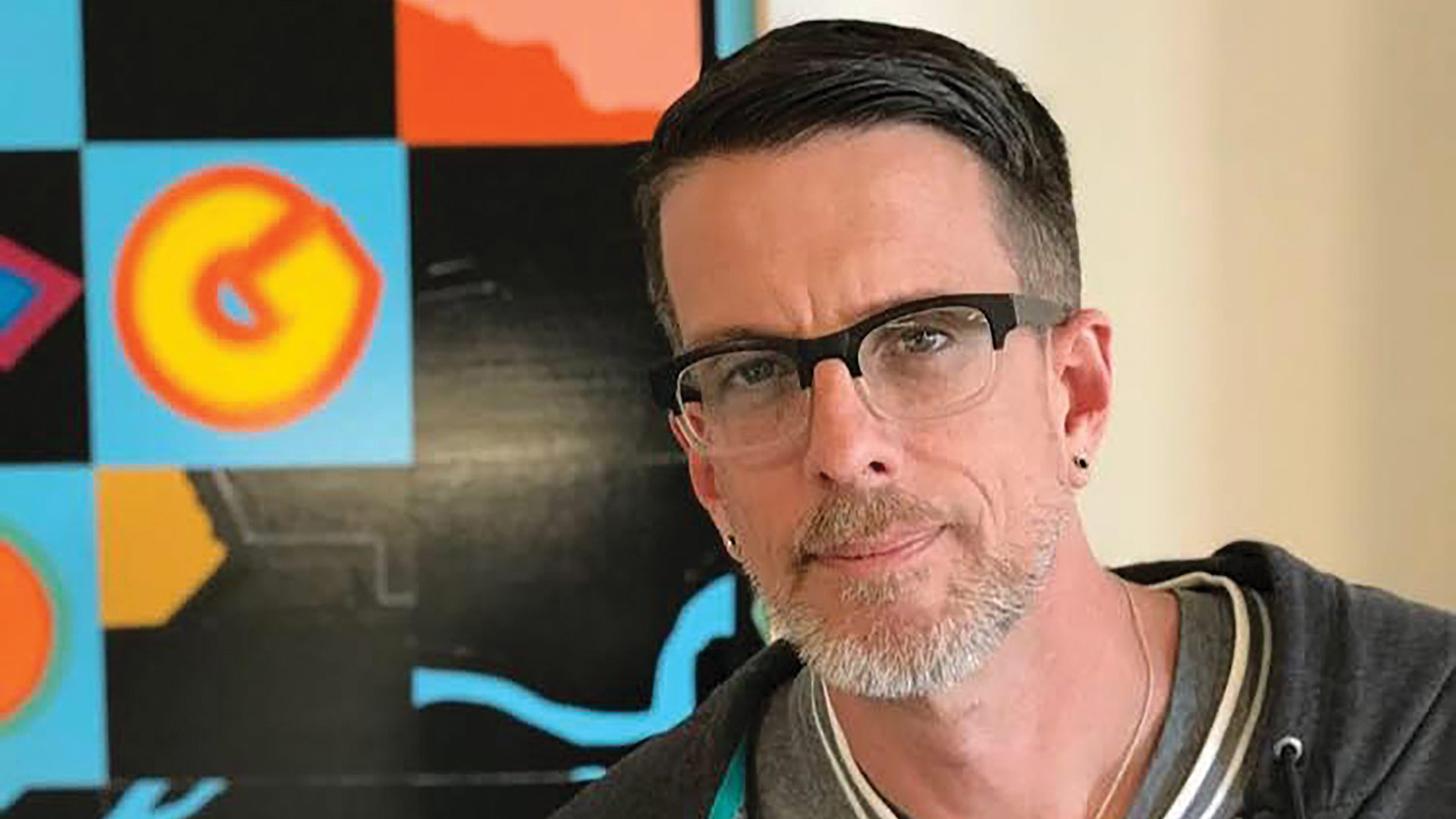

The leaders of Dazed Cannabis hope the recent Monson grand opening isn’t their last, but one of many more.

Photo by Marsco Media for Dazed Cannabis

The discussion these days around a possible ceiling for the industry in Massachusetts doesn’t happen in other sectors, he added. “People don’t talk about us the same way they talk about other businesses, like restaurants, liquor stores. It’s really an open market, a lot of competition. And people are competing. I don’t know that we’re hitting the limit.

“There’s still a lot more legal cannabis dollars that haven’t been realized yet,” he added, citing, again, potential from a massive group of users who currently buy from unregulated sources. “But I don’t think businesses are doing poorly as a whole. I don’t think prices are crashing as much as people suggest. I don’t necessarily see that happening as blatantly as they’re describing it. Businesses still have a lot of growth potential.”

At the end of the day, he added, dispensaries have to offer what people want, and that requires staying ahead of the curve. “There are always new, innovative things coming out in the market. You have to stay up on what’s happening, and with market prices. You try not to be the cheapest on the block because that turns into a whole downward spiral. So you try to have competitive pricing and give people a good customer experience.”

Like all other cannabis entrepreneurs, Vianello hopes for the eventual end of the disconnect between state and federal drug laws that have posed onerous burdens on business owners, from IRS Section 280E, which forbids business owners from deducting otherwise normal business expenses, to hardships around banking, transportation, and other activities.

“That has to happen at some point. I think it’s going to happen. But I don’t think anyone knows when. It’s been right around the corner for years,” he told BusinessWest, acknowledging, like many have, that cannabis is legal for well over half the U.S. population, and bipartisan support exists for decriminalizing cannabis, but lawmakers always seem to have other concerns with which to contend.

“We just act accordingly within the rules in place,” he added. “But we know, if it happens, it will open up a lot of things for a lot of people. We need to have all the same rules and regulations as all businesses, the same opportunities, so we can run these businesses properly.”

Land of Opportunity

The New York location, in Manhattan’s Union Square neighborhood, has certainly been a success story, starting with its origin as a pop-up opened under the state’s CAURD (conditional adult-use retail dispensary) program, which invested in communities and entreprenuers that had been harmed by the war on drugs; Warner, a Harlem native, was arrested in 2008 for trying to buy marijuana during a sting operation, which hindered his ability to find employment afterward.

Now, he and his two partners are the employers at three Dazed stores — with more locations in the works, they hope.

“You try not to be the cheapest on the block because that turns into a whole downward spiral. So you try to have competitive pricing and give people a good customer experience.”

“Keshawn and his dedicated team at Dazed exemplify entrepreneurship in action, shining a spotlight on the importance of social equity in the cannabis industry,” Chris Webber of the New York Social Equity Cannabis Investment Fund said upon the Union Square location’s grand opening in November. “This isn’t just about a dispensary; it’s about leveling the playing field, creating opportunities, and building a more inclusive and dynamic entrepreneurial landscape.”

Vianello said it’s been gratifying to hire locally, providing job opportunities to others.

The interior of the Holyoke dispensary is, like other Dazed shops, resplendent in pink.

Photo by Dazed Cannabis

“That’s the most exciting thing. When we started Dazed in Holyoke, we made a conscious effort to hire hyper-locally. Most of our folks are Holyoke residents or from the surrounding areas, Greater Springfield — but mostly from Holyoke. That’s the entire staff, from the general manager to the newest employee; they’re all local, and they’ve all been promoted and hired from within. And when we had the opportunity to expand into Monson, we were able to bring a lot of those folks over and give them a broader opportunity for employment.”

Indeed, many young people entering the cannabis field recognize it as a new industry with plenty of advancement opportunity.

“We want our team to grow with our expansion, and that’s been good for us to see,” Vianello said. “It’s a new industry, so there’s definitely a lot of opportunities for those folks to grow too. Not everyone has a lot of experience, and those that have experience are super valuable.”

As the cannabis workforce continues to mature and move up, Vianello and his partners are excited to see the industry do the same, despite all the challenges and all the hand wringing over how many dispensaries are too many.

“The thing I like best is that it’s changing and growing, with a lot of different opportunities coming up,” he said. “You just don’t know what’s down the road.”