Robert Johnson Takes the Helm at WNEU

Writing the Next Chapter

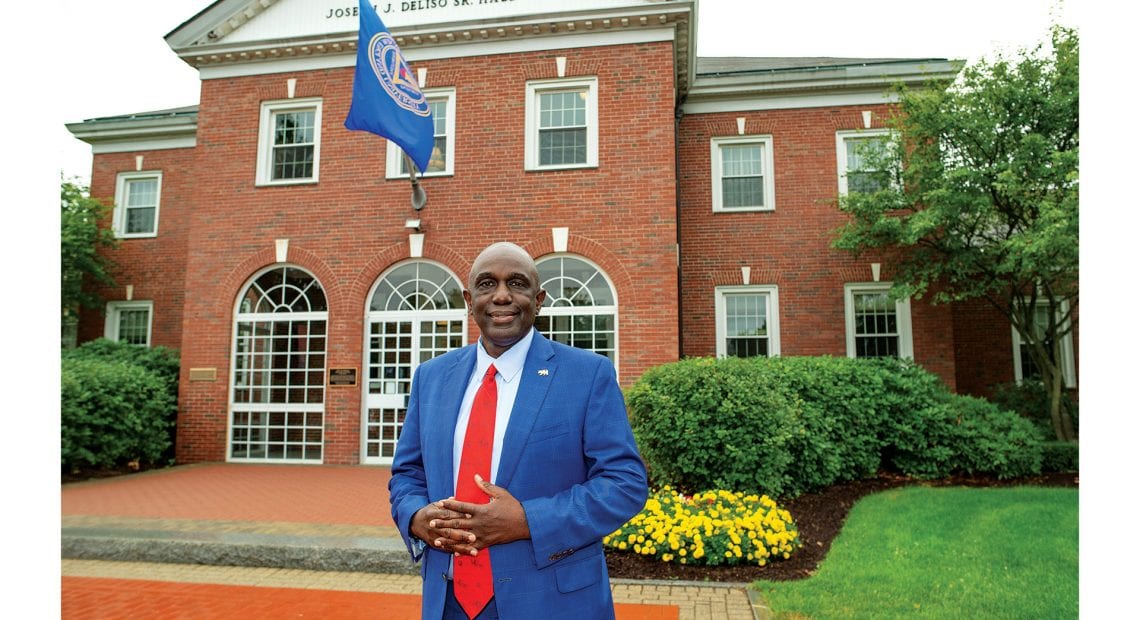

Robert Johnson, president of Western New England University

At least once, and perhaps twice, Robert Johnson strongly considered removing himself from the mix as a search committee narrowed the field of candidates to succeed Anthony Caprio as president of Western New England University (WNEU) in Springfield.

It was early spring, and the COVID-19 pandemic was presenting every institution of higher learning, including UMass-Dartmouth, which he served as chancellor, with a laundry list of stern — and, in some cases, unprecedented — challenges.

Johnson told BusinessWest that the campus needed his full attention and that it might be time to call a halt to his quest for the WNEU job. But he “hung in there,” as he put it, and for the same reason that he eventually decided to pursue the position after at least twice telling a persistent recruiter that he wasn’t really interested.

“We are at an inflection point in higher education,” said Johnson, who arrived on the campus on Aug. 15, just a few weeks before students arrived for the fall semester. “Western New England has a good balance of the liberal arts and the professional schools, along with the law school, that puts it in a unique position to write the next chapter when it comes to what higher education will look like.

“I think it’s fair to say that, when we think about higher education, the last time we’ve seen the level of transformation that is about to happen was just after World War II, with the GI Bill and the creation of more urban public universities, community colleges, and the list goes on,” he continued, as talked through a mask to emphasize the point that they are to be worn at all times on this campus. “As we think about the world of work and the future, colleges and universities will be educating people for jobs that don’t exist yet, utilizing technologies that haven’t been created to solve problems that have yet to be identified.”

Elaborating, he said today’s young people, and he counts his son and daughter in this constituency, are expected to hold upwards of 17 jobs in five different industries (three of which don’t currently exist) during their career. All this begs a question he asked: “what does an institution of higher learning look like in an environment like this, where the pace of change is unlike anything the world has ever seen?”

The short answer — he would give a longer one later — is that this now-101-year-old institution looks a whole lot like WNEU, which, he said, is relatively small, agile, and able to adapt and be nimble, qualities that will certainly be needed as schools of all sizes move to what Johnson called a “clicks and mortar” — or “mortar and clicks” — model of operation that, as those words suggest, blends remote with in-person learning.

The process of changing to this model is clearly being accelerated by the pandemic that accompanies Johnson’s arrival at WNEU, and that has already turned this fall semester upside down and inside out at a number of schools large and small.

“Western New England has a good balance of the liberal arts and the professional schools, along with the law school, that puts it in a unique position to write the next chapter when it comes to what higher education will look like.”

Indeed, a number of schools that opened their campuses to students have already closed them and reverted to remote learning. Meanwhile, others trying to keep campuses open are encountering huge problems — and bad press: Northeastern University recently sent 11 students packing after they violated rules and staged a gathering in one of the living areas, for example, and the University of Alabama has reported more than 1,200 cases on its campus in Tuscaloosa.

It’s very early in the semester, but Johnson is optimistic, even confident, that his new place of employment can avoid such occurrences.

“The decision to go with in-person learning was essentially made before I got here, and I think it was the right decision,” he explained, noting that students are living on campus and only 16% of the courses are being taught fully online, with the rest in-person or a hybrid model. “We’ve tested more than 2,500 individuals, and we’ve had only three positive cases, all asymptomatic. It’s worked out well so far, but this is only the end of the first week.

“We’re cautiously optimistic, and we take it day to day,” he went on, adding that the school’s smaller size and strict set of protocols, such as testing students upon arrival, may help prevent some of those calamities that have visited other institutions. “We’ve been very judicious, and our small size makes us a bit different. We’re kind of like Cheers, where everybody knows your name; we don’t have tens of thousands of students that we have to manage.”

For this issue and its focus on education, BusinessWest talked with Johnson about everything from the business of education in this unsettled time to the next chapter in higher education, which he intends to help write.

Screen Test

Flashing back to that aforementioned search for Caprio’s successor, Johnson noted that it was certainly different than anything he’s experienced before — and he’s been through a number of these, as we’ll see shortly.

Indeed, this was a search in the era of COVID-19, which meant pretty much everything was done remotely, including the later rounds of interviews, which usually involve large numbers of people sitting around a table.

Robert Johnson says he’s confident that WNEU, a smaller, tight-knit school, can avoid some of the problems larger institutions have had when reopening this fall.

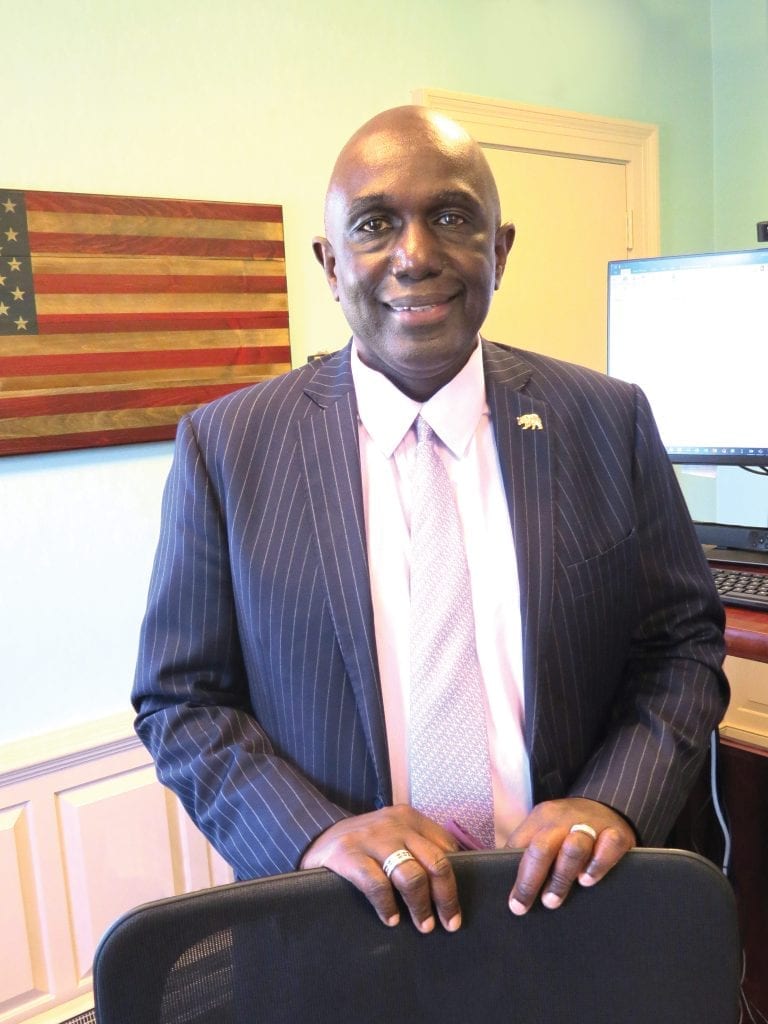

“It was all Zoom, and it was … interesting,” he said of the interview process. “You don’t know if you’re truly connecting or not. As a person being interviewed, you have much more self-awareness of not only what you’re saying but how you’re saying it, and your own non-verbal communication, because you can see yourself on the screen.

“You have to make sure your background is right, the lighting is right, you’re wearing the right colors, all that,” he went on. “It’s like being on TV, literally, because the first impression people get is what they see on screen.”

Those on the search panel were nonetheless obviously impressed, both by what they saw and heard, and also the great depth of experience that Johnson brings to this latest stop in a nearly 30-year career in higher education.

Indeed, Johnson notes, with a discernable amount of pride in his voice, that he has worked at just about every type of higher-education facility.

“I worked in every not-for-profit higher-education sector,” he noted. “Public, private, two-year, four-year, private, Catholic, large, medium, and small — this is my seventh institution. And I think that gives me a unique lens as a leader in higher education.”

Prior to his stint at UMass Dartmouth, he served as president of Becker College in Worcester from 2010 to 2017, and has also held positions at Oakland University in Michigan and Sinclair College, the University of Dayton, and Central State University, all in Ohio.

As noted earlier, when Johnson was invited by a recruiter to consider perhaps making WNEU the next line on his résumé, he was at first reluctant to become a candidate.

“The search consultant, who I happen to know, called me two or three times, and I did not bite,” he noted. “But as she told me more, and I learned more about Western New England University, I began to take a look. I knew about the school, but I had never taken a deep dive into the institution, its history, and what it had to offer.”

He subsequently took this deep dive, liked what he saw, and, as he noted, hung in through the lengthy interview process because of the unique opportunity this job — at this moment in time — presented.

Since arriving on campus, he has made a point of meeting as many staff members and faculty as possible, but this, too, is difficult during the COVID-19 era. Indeed, meetings can involve only a few participants, so, therefore, there must be more of them.

“We can’t have any of those big ‘meet the president’ meetings,” he noted. “So I’ve had six, seven, or eight meetings with small groups or facility and staff, and I probably have another 15 or 20 of those scheduled. I’m getting to know people, and they’re getting to know me; I’m doing a lot of listening and learning.”

Overall, it’s a challenging time in many respects, he said, adding quickly that higher education was challenging before COVID, for reasons ranging from demographics — smaller high-school graduating classes, for starters — to economics and the growing need to provide value at a time when many are questioning the high cost of a college education.

“The business model for higher ed was going to change regardless — I think, by 2025, given demographics and a whole host of other things, colleges and universities were going to have to figure out how to do business differently,” he told BusinessWest. “I think COVID, overnight, expedited that.

“The business model for higher ed was going to change regardless — I think, by 2025, given demographics and a whole host of other things, colleges and universities were going to have to figure out how to do business differently. I think COVID, overnight, expedited that.”

“It was a Monday, and seven to nine days later, every college in the country was teaching remotely and working remotely, in ways we never imagined,” he continued. “So the very idea that colleges and universities will go back to 100% of what that old business model was is a non-starter. So the question is, ‘how do we reinvent ourselves?’”

Courses of Action

As he commenced answering that question, he started by addressing a question that is being asked in every corner of the country. While there is certainly a place for remote learning, he noted, and it will be part of the equation for every institution, it cannot fully replace in-person learning.

“Some would say that online learning is the way, and the path, of the future,” he noted. “I would say online learning is a tool in terms of modality, but it is not the essence of education.”

Elaborating, he said that, for many students, and classes of students, the in-person, on-campus model is one that can not only provide a pathway to a career but also help an individual mature, meet people from different backgrounds, and develop important interpersonal skills.

“Some would say that online learning is the way, and the path, of the future. I would say online learning is a tool in terms of modality, but it is not the essence of education.”

“For the student coming from a wealthy family, I think they need socialization, and they need a face-to-face environment,” he explained. “For the first-generation student whose parents did not go to college, I think they need socialization. And for students who come from poor families, they need socialization.

“My point being that online learning is not a panacea,” he continued. Some would argue that, if you have online learning, it would help poor kids go to college. I would say that the poor kids, the first-generation kids, are the very ones who need to be on that college campus, to socialize and meet people different from themselves. And the same is true for those kids coming from the upper middle class and wealthy families — they need that socialization.

“In my humble opinion, face-to-face never goes away,” he went on. “But does that mean that one might be living on campus five years from now, taking five classes a semester, with maybe one or two of them being online or hybrid? Absolutely. I think the new model is going to be click and mortar, or mortar and click.”

Expanding on that point while explaining what such a model can and ultimately must provide to students, he returned to those numbers he mentioned earlier — 17 jobs in five industries, at least a few of which don’t exist in 2020. Johnson told BusinessWest that a college education will likely only prepare a student for perhaps of the first of these jobs. Beyond that, though, it can provide critical thinking skills and other qualities needed to take on the next 16.

“That very first job that a student gets out of college — they’ve been trained for that. But that fifth job … they have not been trained for that,” he said. “And I think the role of the academy in the 21st century, the new model, is all about giving students and graduates what I call the agile mindset, which is knowledge and the power of learning — giving students essential human skills that cannot be replicated by robots and gives them the mindset to continually add value throughout their professional careers.

“We’re educating people to get that first job, and to create every job after that,” he continued. “We’re making sure that every person who graduates from college is resilient and has social and emotional intelligence and has an entrepreneurial outlook, which is not about being an entrepreneur; it’s about value creation and having those essential human skills. What that means, fundamentally, is that no algorithm will ever put them out of a job.”

To get his point across, he relayed a conversation he had with some students enrolled in a nursing program. “They said, ‘this doesn’t apply to us,’ and I said, ‘yes, it does, because there are robots in Japan that are turning patients over in hospitals. So if you think technology does not impact what you do, you’re mistaken.’”

Summing it all up, he said that, moving forward, and more than ever before, a college education must make the student resilient, something he does not believe can be accomplished solely through online learning.

“How do I put the engineer and the artist together, give them a real-world problem, and say, ‘have at it, go solve it?’” he asked. “They have to be face to face, hands-on. We can come up with alternate reality, virtual reality, and all the technology you want, but at some point, people have to sit down and look each other in the eye.”

Bottom Line

Returning to the subject of the pandemic and the ongoing fall semester, Johnson reiterated his cautious optimism about getting to the finish line without any major incidents, and said simply, “get me to Thanksgiving with everyone still on campus.” That’s when students will be heading for a lengthy break after a semester that started early (late August) and, to steal a line from Bill Belichick, featured no days off — classes were even in session on Labor Day.

But while he wants to get to Thanksgiving, Johnson is, of course, looking much further down the road, to the future of higher education, which is, in some important respects, already here.

He believes WNEU represents that future, and that’s why he “hung in there” during that search process.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]