View Finders

Instrument Technology Inc. Has an Eye on the Future

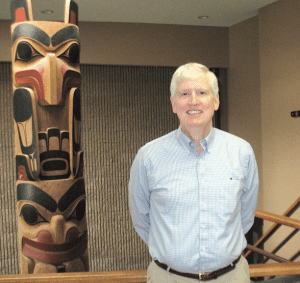

Walk inside the Westfield headquarters of Instrument Technology Inc., and the first thing you’ll notice is the totem pole. It’s kind of hard to miss, rising dramatically up two levels of the front atrium.In fact, an abundance of Native American art graces many of the walls and offices of the facility. ITI President Greg Carignan says there’s a good reason for this, and it has to do with a hobby his father, Donald, stumbled upon by accident decades ago, shortly after founding the company.

“He was on the road, in very remote areas of the United States, calling on nuclear power plants that were usually out in the boonies,” Carignan said. “Usually, there was nothing around except Indian reservations. So, when he had time on his hands, he’d visit these reservations and meet artists, and he started growing an interest in Indian art. He started collecting it, and when his house overflowed, it started coming here. It’s quite a collection.”

Why nuclear power plants? When he launched ITI in 1967 as a manufacturer of optics equipment, the elder Carignan got heavily involved in the nuclear-energy market; “he started building underwater periscopes and wall periscopes to look at the spent fuel rods being stored underwater.”

Greg Carignan explained that, after a period of time, a nuclear fuel rod’s energy is spent, but it’s still radioactive, which has led to debate over the years about establishing a national repository for those spent rods in the Southwest, but bureaucracy and public opposition have made that all but impossible.

“So nuclear plants are required to store spent rods at their facility, mostly underwater, and they’re required to be inspected periodically,” he said. “Dad developed a large-diameter periscope that could go down underwater and look at those spent fuel rods and make sure they’re in good condition. He built quite a few of those scopes in the late ’60s and early ’70s.”

Greg Carignan says the company’s diversity has allowed it to thrive during societal changes, such as a shift away from nuclear power plants.

For this issue’s focus on manufacturing, BusinessWest pays a visit to Instrument Technology, which has been scoping out new opportunities in an intriguing field for the last 45 years — and shows no signs of slowing down the pace of innovation.

Solo Act

Donald Carignan, his son recalled, had a background in optics and worked as a project engineer for American Optical from 1960 to 1966. He then took a job with Kollmorgen Electro-Optical; “that’s where he got his experience building borescopes and periscopes.” Just a year later, he was ready to strike out on his own, launching ITI in Southampton.

“My dad was a pretty driven individual; he worked hard to make it a success,” Greg Carignan said, noting that the company was a bit gypsy-like during its first two decades, moving from Southampton to West Springfield, then to Westfield, and finally to the current facility on the other side of the city in 1985.

“We specialize in the design and manufacturing of remote-viewing instruments,” he explained, noting that the company employs designers and engineers, as well as a full machine shop and assemply department to build the products it designs.

“What is remote viewing? It’s the ability to view a photograph or video-record any area that’s inaccessible or hostile, as well as the ability to view covertly,” he explained. “We added that last portion over the past 20 years because, before that, it hadn’t been used for covert operations.”

But he backed up a bit to describe how ITI has branched into so many diverse fields.

It began with the nuclear-power plants, for which the company developed not only those underwater-viewing scopes, but wall periscopes that allowed workers to see past thick concrete walls into the ‘hot cells’ where radioactive materials were handled. But societal changes that impacted the nuclear-power industry would force ITI to shift its focus — and not for the last time.

“During the Carter years of the late 1970s,” Carignan said, “the nation saw a drastic decline in the number of nuclear facilities being built. And most facilities had our equipment in them. My dad was in need of business, so he looked elsewhere to try to continue moving ITI forward.

“He looked at the industrial market and saw that it was being served by medical endoscopes at the time, and nobody was building industrial borescopes,” he said, noting that the two words are essentially interchangeable, with ‘endoscope’ typically referring to a medical instrument and ‘borescope’ a non-medical one.

“Endoscopes for the human body came on the scene about 40 years ago, but it wasn’t until later on that people figured out they could use the same scopes to look into jet engines, castings, pipes, and other things in industry,” Carignan said. “My dad started working for companies like Pratt & Whitney and General Electric to build delicate industrial borescopes to inspect their engines. They called it the ‘jetscope.’”

Many years ago, he explained, the airline industry had to take apart engines to conduct inspections required by the Federal Aviation Administration — a very costly, time-consuming process. But the development of a flexible borescope that could be inserted into each end of the engine was a revolutionary and cost-saving change.

“Designers started designing points along the engine so they could look in the middle, too,” he said. “You take out a plug and stick in the scope to look at the different sections of the engine.”

During the ’80s and ’90s, the industrial market grew for ITI, and the scopes became more complex, with flexible shafts and articulated tips allowing for more flexible movement.

A Time to Kill, a Time to Heal

Throughout this expansion, ITI hadn’t done anything in the medical market. “But that changed in the 1990s when a company on the West Coast — Accuscan in Mountain View, Calif. — knocked on our door and asked us to make what they called a gastroscope for them,” Carignan said.“They didn’t want to see through it; they didn’t want fibers in it or optics of any kind,” he continued. “They were going to put a transducer in the tip and use it as an ultrasonic device for an esophageal probe down the throat to scope the heart, which is much easier than to try to do it externally and look through the rib cage and all the muscle and fatty tissue.

“We worked with them for a year and a half, and that’s when we started in the medical business,” he continued — a shift that has seen the company produce rigid arthroscopes, ureteroscopes, otoscopes, spine scopes, and laparoscopes; flexible gastroscopes, bronchoscopes, and colonoscopes; as well as equipment for video intubation.

“After 20 years, we’ve become a lot more selective about who we decide to work with,” Carignan said regarding the ideas potential customers pitch to ITI. “If it sounds like a very high risk, or a low chance of successfully bringing it to market, we may not get involved. If it’s a startup company or doctor/inventor that’s asking us to do it on our dime and pay for the development costs, oftentimes we’ll say no.

“The model we’ve come to develop,” he continued, “is companies that have some success already and are willing to share the developent costs of the product.”

Eventually, ITI expanded its offerings even further by getting involved in the law-enforcement and military markets, with products such as telescopic cameras that can see around corners and in darkness, under-door scopes, and scopes that see into rooms using tiny (as small as 2.6 mm) holes in the wall.

“We also needed non-conductive probes that could look into a package or parcel to check if there was anything explosive,” Carignan said. “You don’t want to stick in something metallic that could short the device and cause an explosion.”

The original models used infrared light to expose images, and “that was very successful — then the bad guys figured it out,” Carignan said. “So we were asked to find out new ways of seeing. So we developed a blue-light diode, with different characteristics that wouldn’t trigger detection devices. We always want to stay one step ahead of the bad guys.”

ITI also built a pole camera to look into second stories of buildings, down stairwells, into ceiling tiles, and even underwater. “This was a scope we sold quite a bit of to special-ops groups in Iraq, to clear buildings, streets, and neighborhoods, to look around corners and into rooms where the bad guys might be before clearing out a room. They were eventually used in caves to hunt down Al Qaeda in Afghanistan.”

The wars and Iraq and Afghanistan saw a surge in the production of such devices. Carignan showed BusinessWest a chart breaking down sales from 1999 through 2008, and while medical devices tend to make up the biggest percentage of the company’s sales in a typical year, the law-enforcement and military division took that spot from 2003 through 2006. Meanwhile, sales of industrial scopes have fallen off somewhat over the years, but are rebounding.

Next Generation

The three siblings — Greg, Controller and Purchasing Manager Dawn Carignan Thomas, and Manufacturing Manager Jeff Carignan — admit their devices don’t allow a clear view into the company’s future. With six kids among them, third-generation ownership is always possible.

“We’re wondering where the next generation might take us,” Greg Carignan said, “but it’s still early for that.”

For now, they continue to grow and innovate, scoping out new ideas to help people — manufacturers, surgeons, and soldiers alike — see a lot more clearly.

Joseph Bednar can be reached at [email protected]