Making Change

The manufacturing tech industry is building back fast, undeterred by significant labor and supply-chain challenges. To maintain this momentum, manufacturers should navigate elevated risks while advancing sustainability priorities. That’s the takeaway, at any rate, from a recent Deloitte report exploring five manufacturing industry trends that can help organizations turn risks into advantages and capture growth.

It’s unusual to see positive economic indicators paired with historic labor and supply-chain challenges. But this is the trajectory for the U.S. manufacturing industry in 2022 emerging from the pandemic. The recovery gained momentum in 2021 on the heels of vaccine rollout and rising demand. As industrial production and capacity utilization surpassed pre-pandemic levels this year, strong increases in new orders for all major subsectors signal growth continuing in 2022.

However, optimism around revenue growth is held in check by caution from ongoing risks. Workforce shortages and supply-chain instability are reducing operational efficiency and margins. Business agility can be critical for organizations seeking to operate through the turbulence from an unusually quick economic rebound — and to compete in the next growth period. As leaders look not only to defend against disruption but strengthen their offense, our 2022 manufacturing-industry outlook examines five important trends to consider for manufacturing playbooks in the year ahead.

1. Preparing for the future of work could be critical to resolving current talent scarcity. Record numbers of unfilled jobs are likely to limit higher productivity and growth in 2022, and last year we estimated a shortfall of 2.1 million skilled jobs by 2030. To attract and retain talent, manufacturers should pair strategies such as reskilling with a recasting of their employment brand.

Shrinking the industry’s public perception gap by making manufacturing jobs a more desirable entry point could be critical to meeting hiring needs in 2022. Engagement with a wider talent ecosystem of partners to reach diverse, skilled talent pools can help offset the recent wave of retirements and voluntary exits.

Manufacturing executives may also need to balance goals for retention, culture, and innovation. As flexible work is taking root in offices, manufacturers should explore ways to add flexibility across their organizations in order to attract and retain workers. Organizations that can manage through workforce shortages and a rapid pace of change today can come out ahead.

2. Manufacturers are remaking supply chains for advantage beyond the next disruption. Supply-chain challenges are acute and still unfolding. There’s no mistaking that manufacturers face near-continuous disruptions globally that add costs and test abilities to adapt. Purchasing manager reports continue to reveal systemwide complications from high demand, rising costs of raw materials and freight, and slow deliveries in the U.S.

Transportation challenges are likely to continue in 2022 as well, including driver shortages in trucking and congestion at U.S. container ports. As demand outpaces supply, higher costs are more likely to be passed on to customers.

Root causes for extended U.S. supply-chain instability may include overreliance on low inventories, rationalization of suppliers, and hollowing out of domestic capability. Supply-chain strategies in 2022 are expected to be multi-pronged. Digital supply networks and data analytics can be powerful enablers for more flexible, multi-tiered responses to disruptions.

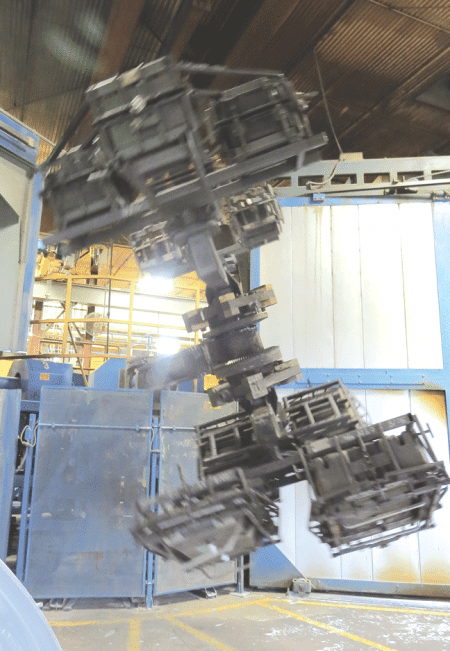

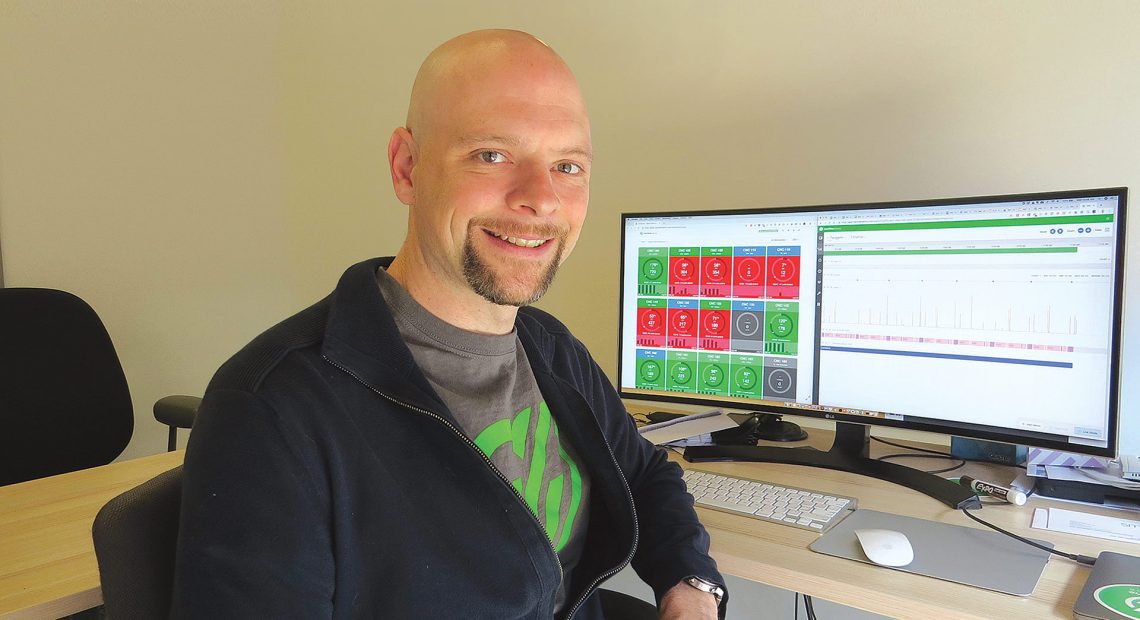

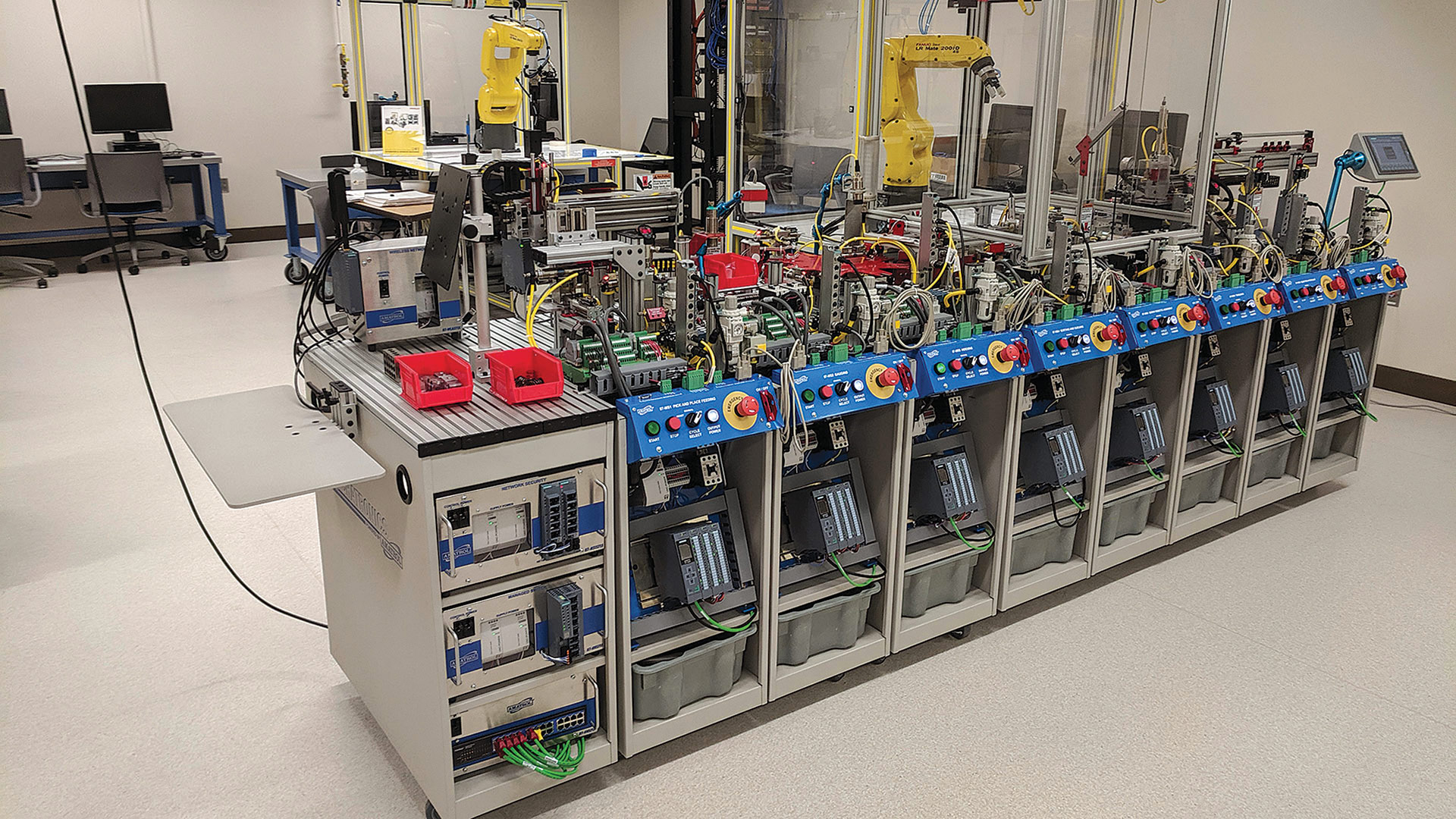

3. Acceleration in digital technology adoption could bring operational efficiencies to scale. Manufacturers looking to capture growth and protect long-term profitability should embrace digital capabilities from corporate functions to the factory floor. Smart factories, including greenfield and brownfield investments for many manufacturers, are viewed as one of the keys to driving competitiveness.

More organizations are making progress and seeing results from more connected, reliable, efficient, and predictive processes at the plant. Emerging and evolving use cases can continue to scale up from isolated in-house technology projects to full production lines or factories, given the right mix of vision and execution.

U.S. manufacturers have room to run with advanced manufacturing compared to many competitors globally. Advanced global ‘lighthouse’ factories showcase the art of the possible in bringing smart manufacturing to scale. Investment in robots, cobots, and artificial intelligence can continue to transform operations. Foundational technologies such as cloud computing enable computational power, visibility, scale, and speed. Industrial 5G deployment may also expand in 2022 along with advances in technology and use cases.

4. Rising cybersecurity threats are leading the industry to new levels of preparedness. High-profile cyberattacks across industries and governments in the past year have elevated cybersecurity as a risk-management essential for most executives and boards. Surging threats during the pandemic added to business risk for manufacturers in the crosshairs for ransomware.

An expanding attack surface from the connection of operational technology (OT), information technology (IT), and external networks requires more controls. Legacy systems and technology weren’t purpose-fit for today’s sophisticated network challenges. Now, remote-work vulnerabilities leave manufacturers even more susceptible to breaches.

Manufacturers should look not only at their cyberdefenses, but also at the resiliency of their business in the event of a cyberattack. Cybercriminals can cause harm beyond intellectual-property theft and financial losses, using malware that now ties in AI and cryptocurrencies. They can also shut down operations and disrupt entire supplier networks, compromising safety as well as productivity. A patchwork of regulations for different industries could be consolidated under the current administration’s ‘whole-of-nation’ approach to protect critical infrastructure. The potential for additional oversight is likely to prompt more industrials to rethink preparedness for crisis response.

5. Manufacturers are likely to bring more resources and rigor to advancing sustainability. The fast rise of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors is redefining and elevating sustainability in manufacturing as never before. Cost of capital can be tied to ratings on ESG, making it a priority for organizational financial health and competitiveness. Expectations for reporting on diversity, equity, and inclusion metrics in manufacturing will likely continue to rise. Board diversity, while progressing slowly, is also showing some momentum. To attract talent and appeal to workforce expectations, most manufacturers are making ESG efforts more visible.

Depending on a manufacturer’s end markets, environmental accountability is increasingly a focus. To develop and deliver against net-zero or carbon-neutral goals, more organizations are dedicating or redesigning sustainability roles and initiatives and quantifying efforts and results around energy consumption. And the fast-evolving ESG landscape may require close monitoring in 2022 for manufacturers.

Many organizations are complying voluntarily within a complex network of reporting regulations, ratings, and disclosure frameworks. But regulators globally are also moving toward requiring disclosure for more non-financial metrics. Proactive approaches may help manufacturers stay ahead of the change and create competitive advantage.

Smith & Wesson’s recently announced plan to move its Springfield operations to Tennessee came as a shock to many — the 165-year-old company has been part of the city’s fabric, and the region’s rich manufacturing history, for generations. Amid questions about the gunmaker’s reasons for moving — the company cites proposed state legislation targeting its products, while some elected officials say it’s more a case of corporate welfare and a better deal down south — the most immediate concerns involve about 550 jobs to be lost. The silver lining is that, with some concerted effort, most of those individuals should be able to find other work locally in a manufacturing landscape that sorely needs the help.

Smith & Wesson’s recently announced plan to move its Springfield operations to Tennessee came as a shock to many — the 165-year-old company has been part of the city’s fabric, and the region’s rich manufacturing history, for generations. Amid questions about the gunmaker’s reasons for moving — the company cites proposed state legislation targeting its products, while some elected officials say it’s more a case of corporate welfare and a better deal down south — the most immediate concerns involve about 550 jobs to be lost. The silver lining is that, with some concerted effort, most of those individuals should be able to find other work locally in a manufacturing landscape that sorely needs the help.

President Trump has made no secret of his hope that a series of tariffs on goods from China and other countries will eventually force a more favorable balance of trade for the U.S. But in the meantime, the escalating trade war has posed very real, often negative impacts for manufacturers, particularly in the form of higher costs and a general sense of uncertainty that makes it difficult to pursue growth. And no one seems to have any idea when the situation will ease up.

President Trump has made no secret of his hope that a series of tariffs on goods from China and other countries will eventually force a more favorable balance of trade for the U.S. But in the meantime, the escalating trade war has posed very real, often negative impacts for manufacturers, particularly in the form of higher costs and a general sense of uncertainty that makes it difficult to pursue growth. And no one seems to have any idea when the situation will ease up.