Taking Center Stage

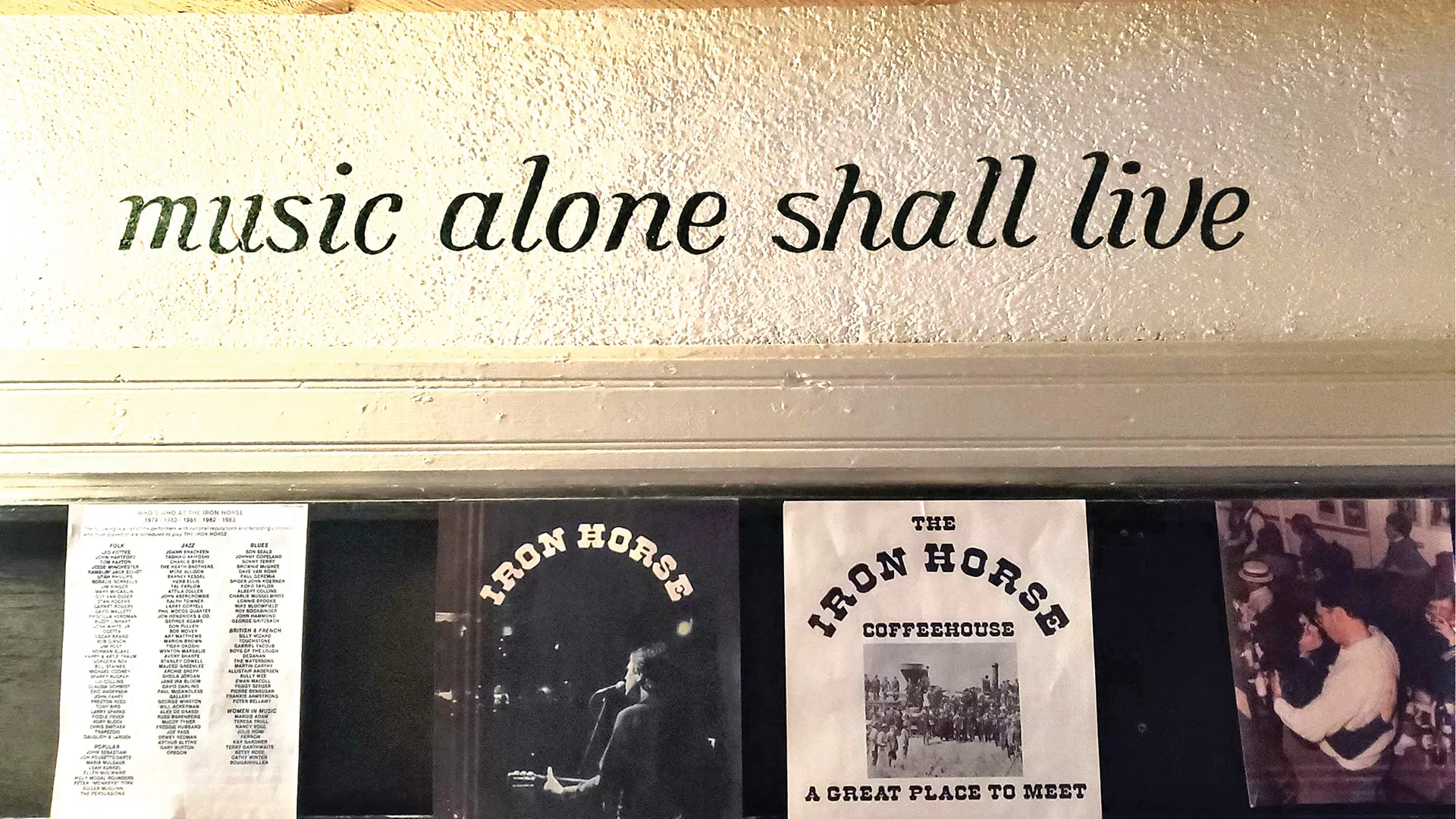

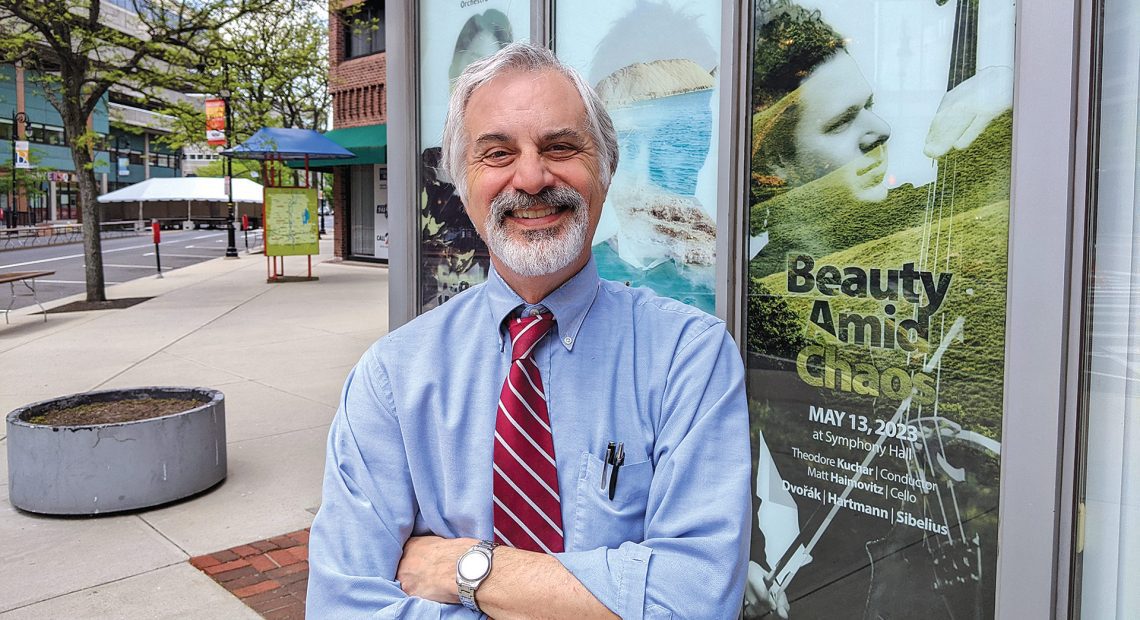

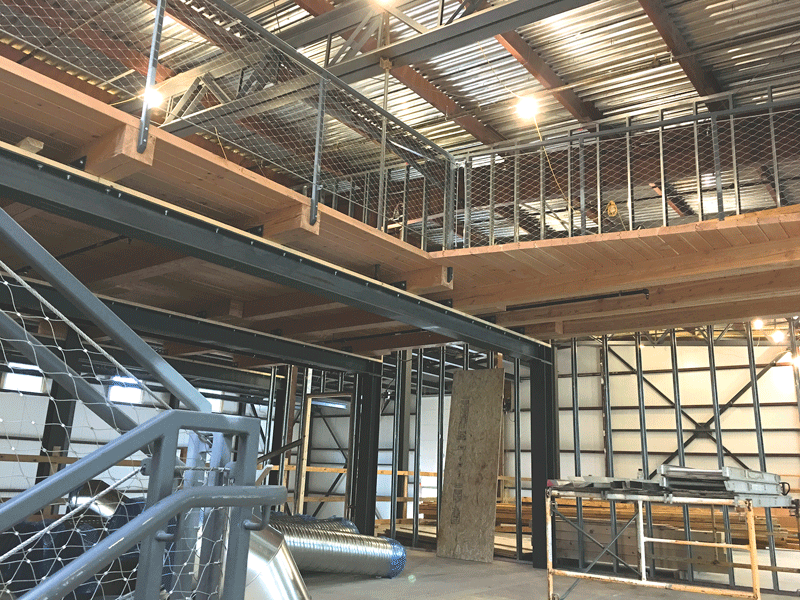

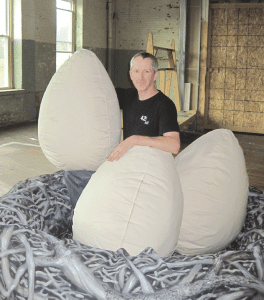

Angela Park and Dan McKellick stand in the balcony at 52 Sumner.

Angela Park was originally looking for a home for her business, one that specializes in after-school programs for young people.

And she essentially found one in a portion of Faith United Church on Sumner Avenue in Springfield, a 125-year-old landmark that had recently come on the market amid declining church membership.

As she and other partners moved forward with the acquisition, an obvious question arose — what to do with the nave, altar, and even the balcony of the structure?

The eventual answer to the question — and it took some time for it to be answered — has become one of the more intriguing cultural developments in Springfield for quite some time.

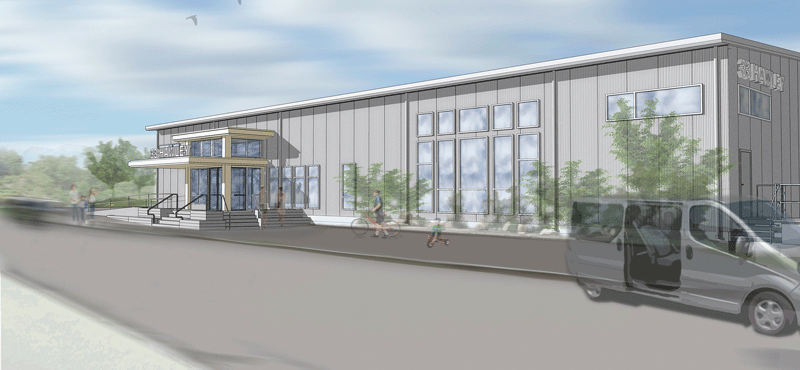

Indeed, Park and others have created a nonprofit called Springfield Performing Arts Ventures Inc. (SPAV) and, in the church sanctuary, a new venue for the arts called 52 Sumner — the structure’s street address.

“We are committed to breaking down barriers, ensuring that everyone, regardless of background, can access, participate in, and be inspired by the arts.”

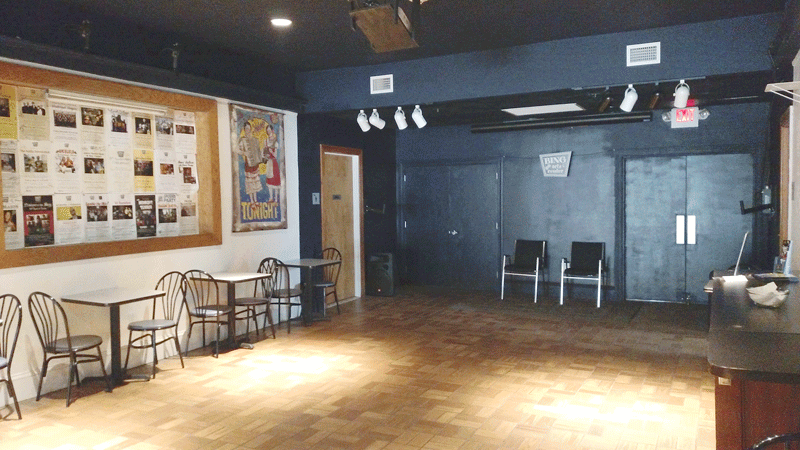

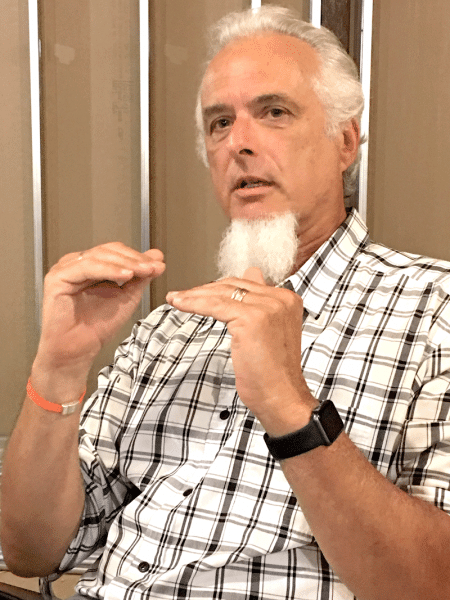

After more than a year’s work to renovate the hall, remove its pews, and install a new sound and lighting system, the venue officially opened earlier this year. There are several events on the schedule, and the obvious goal is to add more, said Park, executive director of SPAV, and attorney Dan McKellick, a member of the agency’s board of directors.

But its broad mission goes much further than merely staging concerts and other forms of entertainment in a unique environment that many potential patrons can walk to.

“Our mission is to spark the artistic spirit within our urban community, providing a haven for creative expression, cultural enrichment, and personal growth through the arts,” said McKellick, quoting the agency’s mission statement but adding emphasis to those stated goals. “We are committed to breaking down barriers, ensuring that everyone, regardless of background, can access, participate in, and be inspired by the arts. Through education, performance, and outreach, we strive to foster a more vibrant, connected, and culturally enriched city, promoting unity and understanding among all our residents.”

Elaborating, McKellick said the agency, with this venue, is focused on bringing many different types of performing arts to Springfield and the region — not just specific acts, but cultural experiences, as we’ll see.

52 Sumner has already hosted several events and has many more on the calendar.

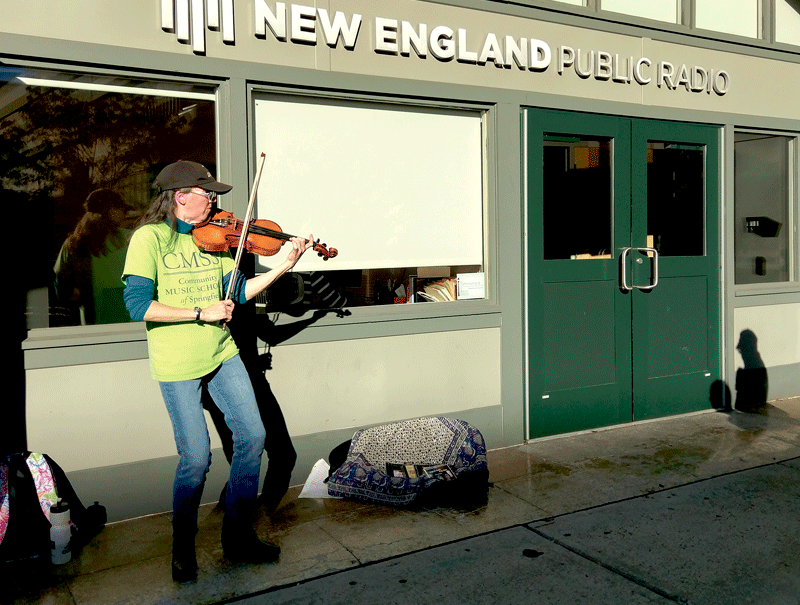

“This is a unique opportunity to bring all different sorts of arts,” he explained. “It’s not just limited to musical performances; we look forward to being able to host everything from acting clubs — there are many drama clubs around — to different types of music. I like to say that we’re providing an experience.”

As was the case late last month, when the Irish band the Screaming Orphans gave a performance at the venue, along with students from a local Irish step-dance school as an opening act.

And later this month, a Latin Fusion band called DAR & the Rebel Monks, based in Hartford, Conn., will be performing.

“They have a Grammy Award-winning artist in their band, and they have two members of their band who are backup band members for Jose Feliciano,” McKellick said, adding that this performance will follow a salsa instructor, and there will be Latino-themed finger foods.

“When you come out and buy a ticket, you’re not just seeing a band, having a couple of drinks, and going,” he said. “You’ll have the opportunity, in this case, to immerse yourself in the culture and connect a little more with that culture.”

“When you come out and buy a ticket, you’re not just seeing a band, having a couple of drinks, and going. You’ll have the opportunity, in this case, to immerse yourself in the culture and connect a little more with that culture.”

Meanwhile, these acts will provide working capital to the agency, said McKellick, adding that the proceeds will be used to bring community programming to the venue, such as performances for young people, art lessons, drama workshops, pottery lessons, and more.

This is part of the mission and a big part of what makes this venue and what’s happening there unique, said Park, adding that the agency is “trying to let out line slow,” as she put it, while putting together a slate of performances and drawing people from across the 413, and well beyond, to a very different kind of performance venue.

“There are a lot of people who want to get involved and have things here,” she said, adding that there is a high level of anticipation about what this venue can become in the years to come.

For this issue and its focus on the creative economy, we’ll look at how 52 Sumner came to be, how it plans to carry out its unique mission, and why it is a provocative addition to the cultural landscape in the region — for many different reasons.

Sound Decisions

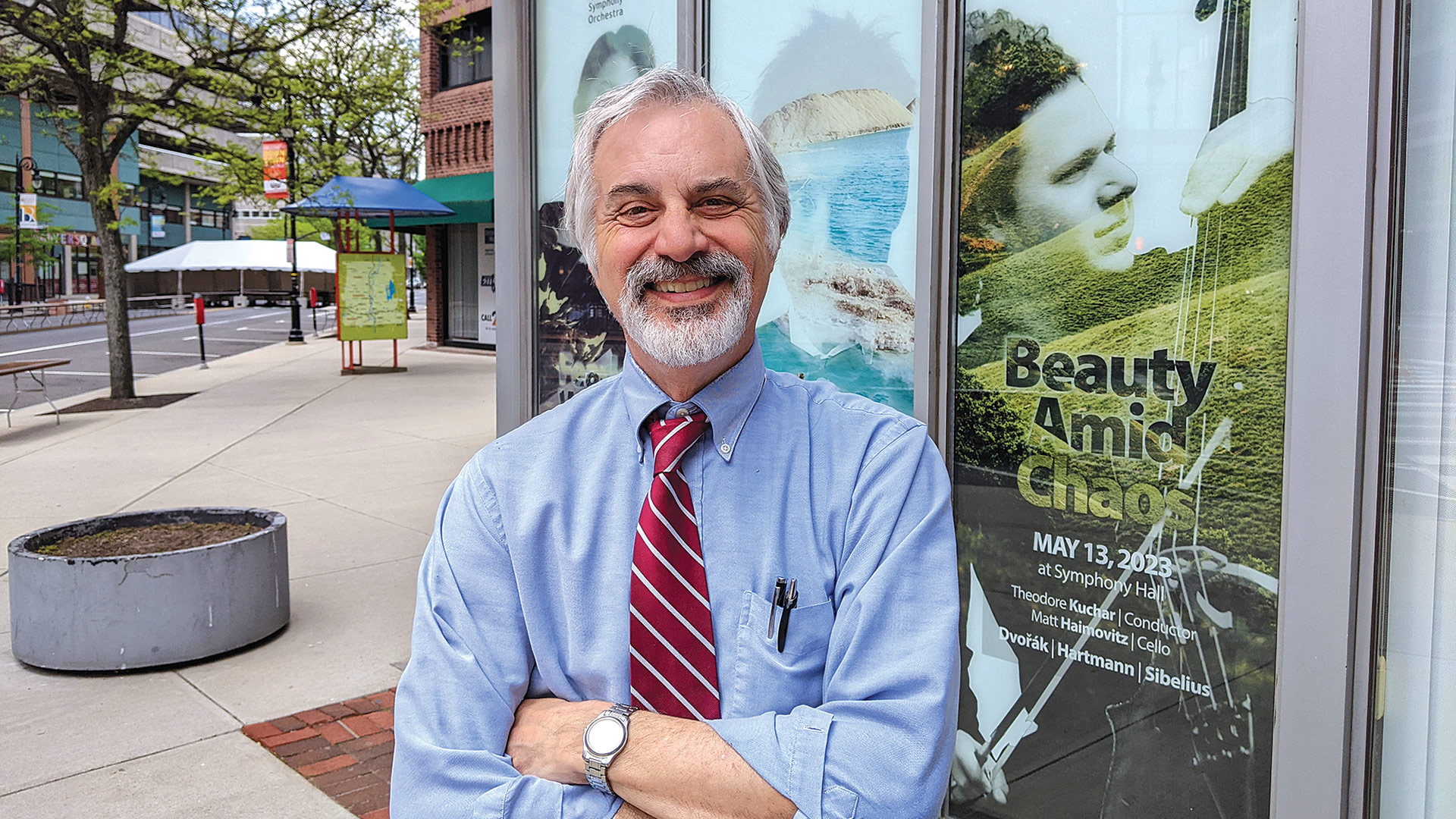

It’s called the Edgar Allan Poe Speakeasy.

And it’s described thusly: “Over a century and a half after Edgar Allan Poe’s death, this cocktail experience brings the most beloved works of Poe to life off the page and onto the stage. Our immersive evening pairs four tales with a dash and history and heavy libations.”

Those presenting the program are among the many varied groups who have reached out to SPAV about performing at 52 Sumner, said Park, noting that the strong interest to date, which comes from several local bands, theater groups, and more, speaks to just how quickly this new venue has captured the imagination of the arts community. And held it.

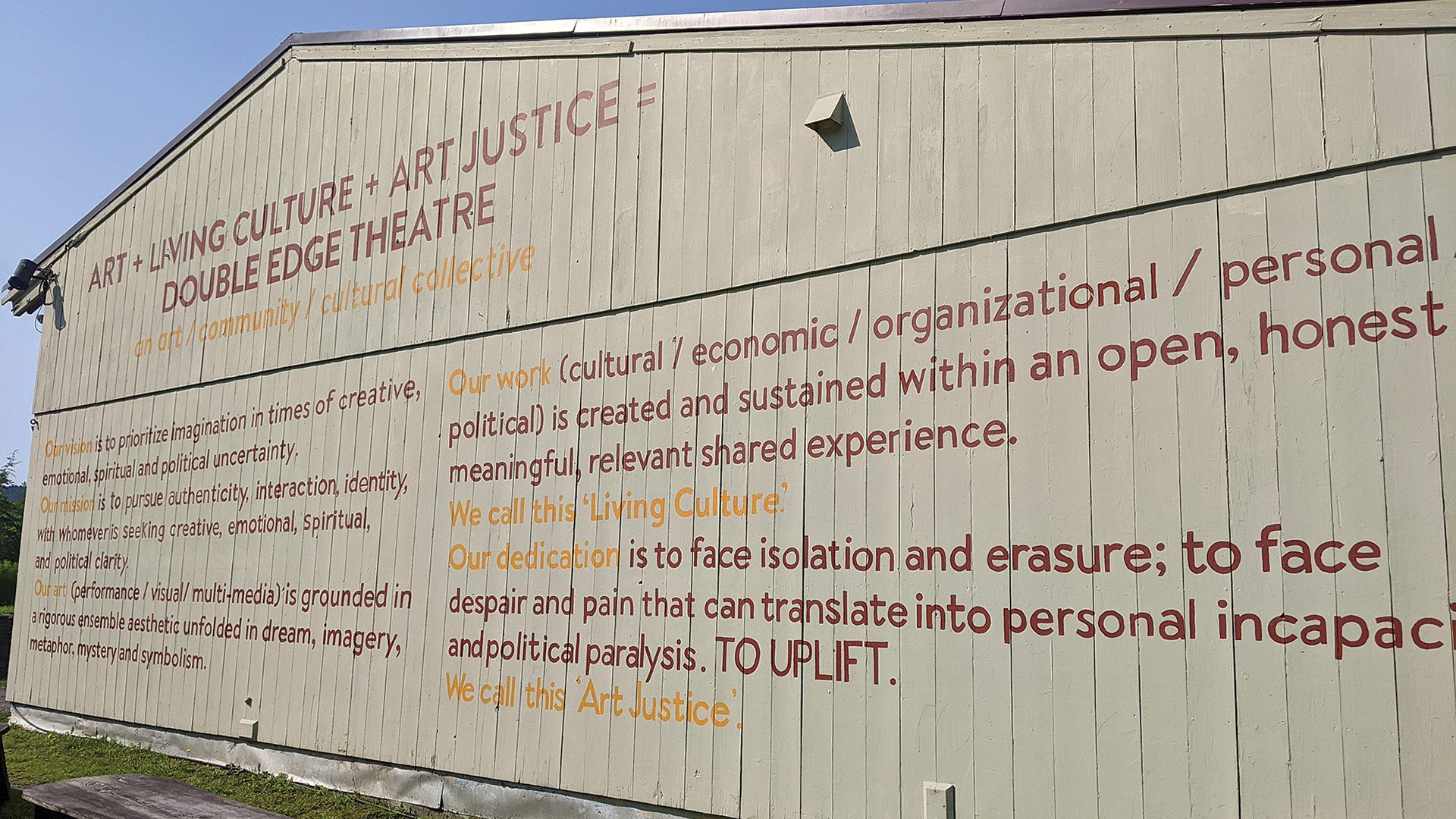

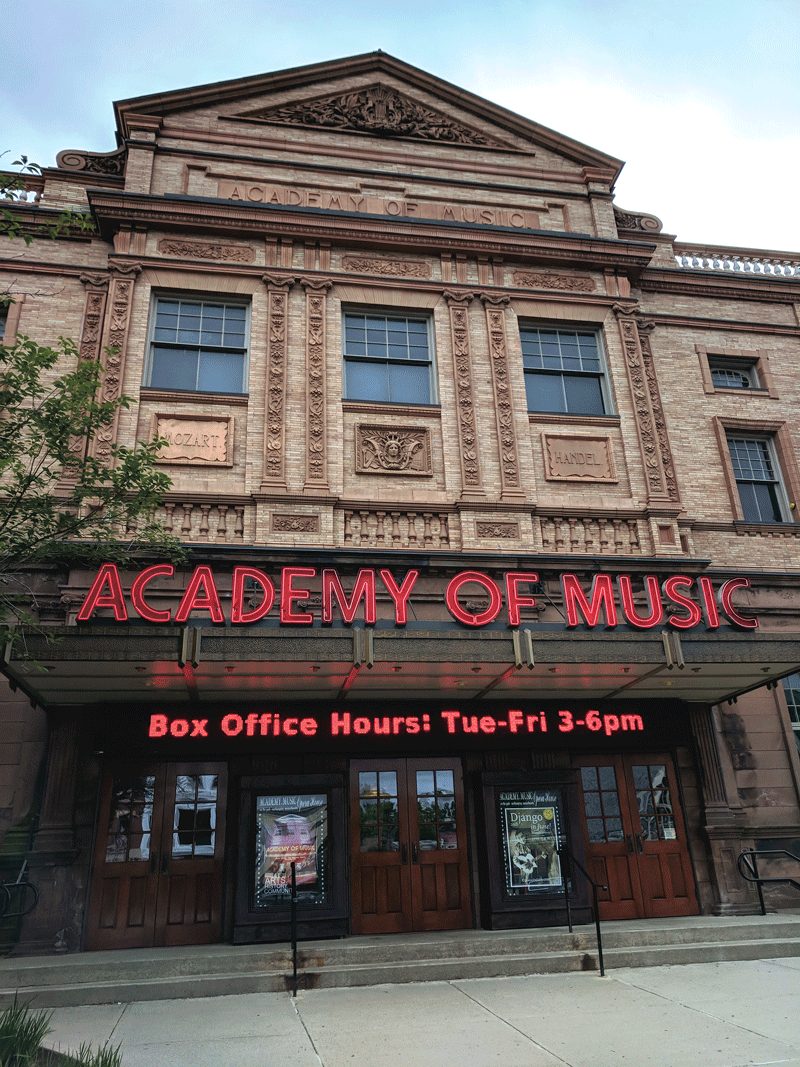

An undated picture of Faith United Church.

Looking back, those with the original vision said this is what they had in mind — sort of. From the beginning, they thought they had something unique, something special. It took some time to see just how special.

Our story begins in 2019, when Faith United Church closed amid declining membership. The property became one of several houses of worship to come on the market in recent years for essentially that reason.

The church, designed by renowned architect William Van Alen, noted for his design of New York’s Chrysler Building, was on the market for a few years when it came to the attention of Park and her business partner, who were looking for another location for their after-school programs. They eventually acquired it for $525,000.

With those programs and a daycare facility as tenants, the overriding question, as noted earlier, involved what to do the sanctuary portion of the building. Soon, plans for a performance venue started to develop, and over the course of a year they came together, along with the nonprofit Springfield Performing Arts Ventures Inc. and its broad mission.

The needed renovations were fairly extensive, said McKellick, noting that the floors had to be refinished and the hall repainted, a large project requiring specific expertise because of the height of the hall. Acoustic panels were added as well as sound and lighting systems, he went on, noting that the work was completed late last year.

Meanwhile, the necessary permits were obtained. Working with the city, parking was secured at a long-closed Friendly’s (now owned by the city) across the street from the church, with additional parking on the street and in a small lot behind the church.

An open house to showcase the space, which doubled as a fundraiser for Toys for Tots, was staged on Dec. 7, with the first actual performance on Feb. 17, featuring two local groups, Moses Sole and the 413s. Those performances, which drew more than 400 people, served as an opportunity to test all the systems and make sure all was in in order, said McKellick, adding that those tests were passed.

Overall, the goal is to bring live performances to the area, but at an affordable price — $17 for the performance in March involving the Screaming Orphans and the Irish dancers, and $20 for DAR & the Rebel Monks — although there’s an early-bird price of $15.

“You can come in for $15, get a salsa lesson, dance a little bit, enjoy a band that has all these really talented artists, dance some more, enjoy some food … that’s a pretty good value,” he said, adding that, as a nonprofit with a mission of breaking down barriers to the arts, affordability is an important aspect of this venture.

Art and Soul

Equally important is the resolve to create community programming for various audiences, but especially young people, said Park and McKellick, noting that this is why the schedule includes an important fundraiser, set for May 28.

Organizers have received a commitment from Christone ‘Kingfish’ Ingram, a Grammy-winning blues artist, to play at that event, who was secured through “a cold call, lots of follow-up, and lots of horse trading.”

“I noticed that he was passing through,” said McKellick, noting that Kingfish — Ingram’s stage name — was playing an event in Boston and then heading to Vermont for a string of performances.

He will headline the fundraiser, which will hopefully raise $100,000 and thus help defray the cost of several summer programs that SPAV is planning, which speaks to the group’s larger mission: to go well beyond being a performance venue and instead become a vehicle for introducing constituencies, and especially young people, to the arts and immersing people in them.

Indeed, as noted earlier, the stated goal is to use the proceeds from various performances, and fundraising efforts, to fund community programs, from pottery classes to drama workshops, McKellick said.

“If we can find the instructor and we can figure out how to do it, we want to create affordable access to the arts for the kids in our community, because it’s super expensive, just like everything else — a gallon of milk, a dozen eggs … everything has gone up in price, and it’s really hard.

“To try to pull them away from wherever they are and keep them inspired by the arts, whether it’s the music side, the performing-arts side, or the artistic side, the hands-on side … that’s what we want to do,” he added.

To that end, those at SPAV are working to book some “symphony-like concerts” for young people as well other types of performances, including one involving someone called ‘Father Goose.’

This would be Wayne Rhoden, a Grammy-winning singer, songwriter, and music producer, said McKellick, adding that SPAV is trying to book him for several shows, what he called “field-trip” performances.

Meanwhile, the space is available to rent for corporate outings, nonprofit fundraisers, various types of performing arts (including dramatic productions), and other events, and it has already staged several, said Park, adding that there are several revenue streams that will help the agency carry out its mission.

Overall, SPAV and 52 Sumner are writing the early chapters of an intriguing story that has brought new life to a Springfield landmark and the promise of not just art, but the ability for diverse audiences to enjoy it, take part in it, and, hopefully, become immersed in it.

In short, it’s a work in progress, and a work of art — or the arts, to be more precise.