Life Lessons

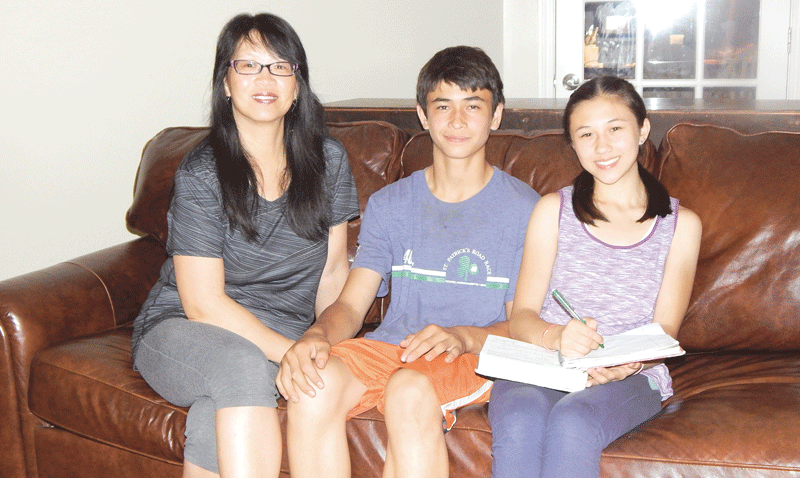

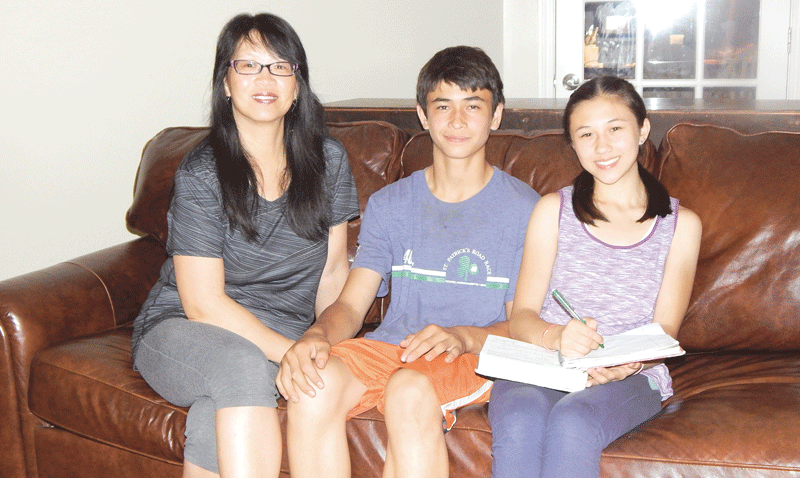

Jean Pao Wilson homeschooled her son Dillan for six years until he chose to enter public school, and still homeschools her 13-year-old daughter Amelia.

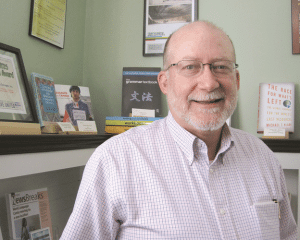

Jean Pao Wilson will never forget the moment she decided to homeschool her children.

“I can still see the picture in my head; my children were sitting on my husband’s knees on the riding mower as the sun set behind them,” the Easthampton mother said, adding that she had returned home from running errands, and although it was past their bedtime, her son and daughter ran and jumped into their father’s lap as soon as they saw him.

“It was a deciding moment; my son was in kindergarten and I had been thinking about the idea, but that did it,” Pao Wilson said, explaining that her husband worked six days a week, her children were in bed every night when he got home, and she knew homeschooling would allow them to spend more time together.

Other local parents who homeschool may not have experienced a similar epiphany, but those who have chosen this route say the benefits outweigh the challenges, and they and their children have no regrets.

Indeed, 16-year-old Dillan Wilson, who made the decision to switch to a brick-and-mortar school in seventh grade after years of homeschooling, found his experiences with learning very different than many of his peers.

“I saw so many kids who were just trying to get a (grade of) 60 to pass a test, rather than really wanting to understand the material,” he explained. “If I hadn’t been homeschooled for so many years, I might have been one of them.

“Homeschooling was a good experience,” he continued. “It wasn’t over-structured and I always wanted to learn more because there was never any pressure or testing.”

Statistician Sarah Grady from the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics said the organization’s most recent study on homeschooling has yet to be released. But there was a 74% increase in homeschooling from 1999 to 2003, a 36% increase over the next nine years, and by 2012, 3.4% of students in the U.S. were homeschooled, including 31,000 to 41,000 children in Massachusetts.

Grady said the majority of parents cited concern about the environment in schools as the primary reason they decided to homeschool. However, the numbers reflect a limited population; 83% are white, and the income for most households is $50,000 to $100,000.

But local parents say the benefits are numerous: Homeschooling can be tailored to meet each child’s need; each child has a one-on-one-tutor; they can learn at their own pace without being labeled, which is especially important if they are ahead or behind in a subject area; they learn to think more independently than their peers; they are not bored by subjects they lack interest in or have already mastered; the environment is safe and devoid of bullying; and unusually close family relationships are forged due to a lifestyle that incorporates learning at every level.

Which is not to say that parents never have doubts.

David Iacobucci of East Longmeadow is a middle-school vice principal, and when his wife Adriana told him she wanted to homeschool their children he was apprehensive because he lacked a true understanding of the possibilities.

But over the years, a series of small and consistent successes that began when he watched Adriana teach his children to read built a belief in homeschooling that exceeded anything he could have imagined.

It has involved a lot of lot of hard work; the couple has studied Massachusetts and Connecticut state standards, and David has provided Adriana with many resources gleaned from his own career. But ultimately, he discovered that what was taking place in his home was the ideal set for public schools: Student-centered learning with an unlimited opportunity for socialization through a full schedule of diverse activities.

But he admits he continued to have some reservations, although they diminished over time, until his oldest daughter, Lena, got her first report card in a brick-and-mortar high school.

Today, Lena is a senior and president of the National Honor Society in East Longmeadow High School; her younger sister Sofia, who entered public school in 7th grade, has also earned honors, including the Presidential Award for Academic Excellence in eighth grade; and 11-year-old Eliza and 8-year-old Luca are being homeschooled by Adriana.

For this edition and its focus on education, BusinessWest takes a look at homeschooling through the eyes of several local families who shared their fears, hopes, and dreams, and the challenges and rewards of this form of alternative education.

Unlimited Resources

Miranda Shannon of Amherst started homeschooling 16 years ago. Today, one of her children is in graduate school, two are in college, her 18-year-old just finished his high school homeschooling program, and her 14-year-old son is still being homeschooled.

“Homeschooling is a viable way to educate children that can be done successfully because it allows parents to take their children’s personalities and learning styles into account; the ultimate goal is to produce an educated, self-confident young person,” Shannon told BusinessWest, noting that it’s more accepted today than when she started more than a decade ago.

Shannon is the moderator for the Pioneer Valley Homeschoolers Group, an inclusive, eclectic, online support group started in 2000 by a handful of families in a playgroup who shared the same goals.

It’s a place where people can find resources, ask questions, get advice and support, and post events, classes, and other activities. The group also offers help on tasks that include how to turn in paperwork required by local school departments as well as other practical information.

“There are things that every family must do, but when it comes to actual teaching we all do things very differently,” Shannon said, noting that PVHG provides support at all stages of schooling, from preschool/kindergarten through high school, which is important; veteran homeschoolers, who schooled their teens through high school give advice to families who wish to do the same.

The help ranges from information about existing options to advice on how to create high school transcripts, and personal experiences with the college application process.

Adrianna Iacobucci helps 11-year-old Eliza and 8-year-old Luca with their studies.

Indeed, so many groups exist in which homeschoolers and parents collaborate that it’s not difficult for parents to find one with like-minded people; they include cooperatives where group learning and projects are the primary focus; clubs formed by parents; support groups; and a growing number of field trips, classes, and educational sessions.

Sophia Sayigh is on the board of directors for Advocates for Home Education in Massachusetts; the statewide nonprofit is based in the Boston area and designed to educate and support parents in the Commonwealth who want to homeschool their children.

She says each town or city is responsible for overseeing residents who are homeschooled, and parents must submit an annual plan for each child. However, there is considerable room for flexibility because homeschoolers are not required to take standardized tests, although they can take an exam similar to the GED if they want a traditional diploma.

But experts say that is not necessary for entrance to college, especially at private schools, and an article in the Journal of College Admission notes that homeschoolers’ ACT and SAT scores are higher than those of public school students, and home-educated college students perform as well as or better than traditionally educated students.

Although some parents use curriculums they purchase to help guide their daily lessons, many create their own based on state standards. The Internet also provides an unlimited trove of resources: Lena Iacobucci took a free college course in psychology when she was in 8th grade, and her sister Sofia took a college course in International Law while she in 6th grade, thanks to offerings on the website www.coursera.org.

Sayigh tells parents to consider their child’s interests and how they learn best and include that in their education plan, and notes that being able to cater to their individual needs is one of the benefits of homeschooling.

“Everything is interdisciplinary,” she said, explaining that although schools divide their day into periods with designated times for different subjects, taking a child who is fascinated by marine biology to an aquarium can lead to extensive reading, research, writing, and math exercises that the child finds interesting. And since children learn best when they are enthusiastic about a subject, it can result in advanced learning.

In fact, homeschooling is an experience far removed from what most people imagine.

“You do not have to recreate school at home; there is no school bus to catch, and if something isn’t working, you change it,” Sayigh said. “Plus, your child doesn’t ever have to struggle because their learning is not dictated by an outside institution.

“Although you need to be able show progress, they don’t have to be at grade level in every subject,” she continued, citing the example of learning to read; there is a continuum of normal, and if parents read to their children every day and take other measures that hold their interest, they attain competence in their own timeframe.

Shattering Misconceptions

Homeschooling parents agree that although it can be a lifesaver for some children, it is definitely not for everyone, and is unlikely to be successful if the parent’s and children’s personalities do not mesh well, or for those unwilling to make the effort required to ensure their children have a multitude of opportunities to interact socially with their peers.

“If the parent is on the quiet or shy side, it may be hard to provide enough socialization for their children,” said Pao-Wilson, a licensed clinical psychologist. “It takes energy and time to network and establish and build the relationships and support that you and your children need.”

Local homeschooling parents say they don’t sit at the kitchen table for six hours a day, and their schedules are much different than one would find in a traditional school setting. Most tackle academic subjects such as math and language arts in the morning, because children learn best when they are not tired.

But their afternoons vary; children meet and do projects or learn lessons with co-op groups, take field trips, do volunteer work, research, read, take part in organized sports, and participate in the many programs that have sprung up in recent years at local museums, nature centers, and other facilities offering programs expressly for home-schooled students.

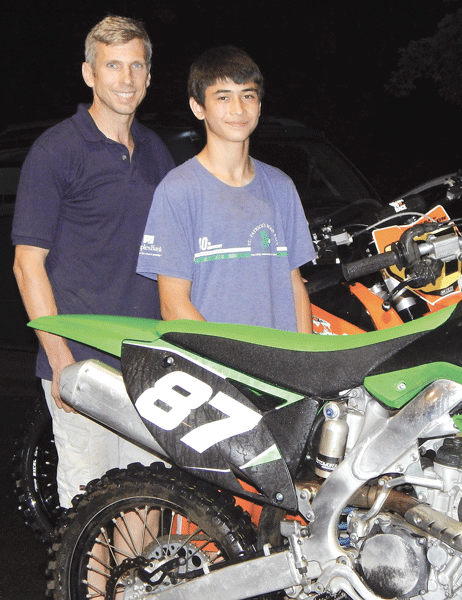

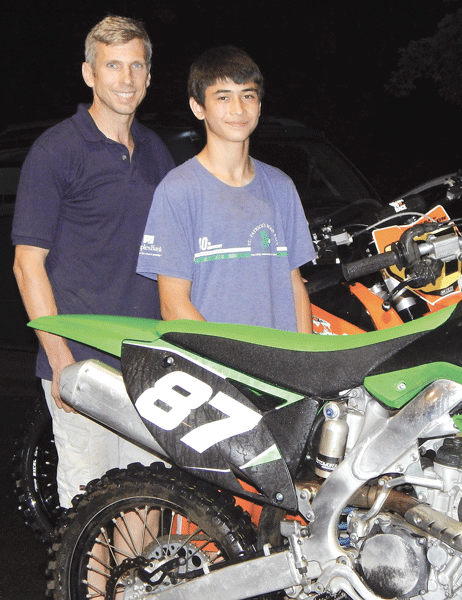

Gary Pao Wilson and his son Dillan share a close relationship and many interests, which was the intent behind Jean Pao Wilson’s decision to homeschool their children.

For example, Springfield College started a free physical education program last year for homeschoolers that divides them by age and meets on Friday mornings.

“All aspects of the program are directly supervised by Springfield College faculty members,” said Springfield College PEHE Chairman Stephen C. Coulon. “The physical education instruction is offered in a supportive environment with the emphasis on achievement and enjoyment.”

Parents also start their own groups. Pao Wilson and another homeschooling mother received a STEM grant from 4-H to start a Science Club, and was helped by two friends; a molecular cellular biologist and a friend with a degree in astrophysics.

“I know it’s incumbent on me to find programs that will interest my children, and if something doesn’t exist, I need to create it or find resources that will help me,” she said.

Most children’s schedules are filled with activities and trips to places that interest them, and they also belong to Girl Scouts, Cub Scouts, local sports teams, and more.

Social skills are formed as they work on projects in homeschool cooperatives and through the many group activities they take part in. In fact, parents and children say that being in a classroom doesn’t mean you will make friends with the people around you, and that it’s easy for them to form friendships in a homeschooling environment.

“You don’t need to be with 30 kids a day to develop as a normal, happy person, and homeschooled children are often more comfortable with adults because they don’t view them as someone who is trying to keep them in order,” Sayigh noted, adding that she successfully homeschooled her two children.

Different Styles

Pao Wilson does not think of homeschooling as simply another way to master academics; instead she views it as a place to learn lessons about life; develop critical thinking skills; and share her personal values.

And since most homeschoolers engage in a wide variety of activities related to their schooling, that’s exactly what has occurred with her children.

Her daughter Amelia, has earned ribbons for science-related projects in 4-H; taken photography classes, and pursued other things that interest her.

And although Dillan chose to leave homeschooling for a traditional education, 13-year-old Amelia tried an English class, then decided she wants to continue learning at home.

“I can do things at my own pace at home. It’s easier than having a schedule,” she said, adding that she likes the flexibility of being able to take a break when she gets tired.

Her outside activities include horseback riding, but she says she is very self-motivated when it comes to schoolwork.

“My mom is always there if I have questions, and I don’t have to wait for an e-mail or a phone call to get the answer,” she continued, citing the benefits. “Some of my friends wish they were homeschooled.”

Pao Wilson and other parents say they were initially apprehensive about their ability to teach their children, but when doubt arises, she recognizes it’s something she has to make peace with.

But it quickly became clear that she had to spend time on her relationship with her children and their relationships with each other; they had to learn to negotiate and resolve conflicts with each other, express their emotions, and get along.

“I had to change my style of parenting, and by the time they were 10 and 8, I was talking to them like they were teenagers,” she said. “But they were able to develop their own thoughts about things without worrying about conforming to the norm or being subjected to the pressure of how others perceive them.”

Adriana Iacobucci, who has homeschooled for 13 years, said she and her husband David gave their children choices from the time they were toddlers, and the decision to homeschool evolved after their oldest daughter Lena returned from preschool and announced she could learn the same things at home.

“We wanted them to be self-directed learners,” she said, adding that homeschooling families learn quickly to respect and support one another even if their teaching styles are very different.

Like other parents, she has moments of doubt, but she also views it as a challenge that must be overcome. But she has been part of many co-op groups, and continues to make a concerted effort to involve her children in as many activities as possible.

“They have been in many situations with diverse families, so they’re open minded about other people and really accept them,” she noted. “Our children are also extremely independent; making decisions about their own academic studies has spilled over into how they spend their time and who they spend it with.”

She has enjoyed watching them learn, and says it’s a luxury to allow them the time and space they need to master subjects they find challenging.

Eliza is still at home, and the 11-year-old enjoys her lifestyle. “I like being homeschooled, although I definitely do want to go to high school,” she said.

Her 8-year-old brother Luca also likes being homeschooled. “You don’t have to be in class as long,” he said, reciting subjects he enjoys, including science and math.

Difficult Lessons

Pao Wilson says homeschooling requires parents to learn how to learn themselves, have a desire to examine their beliefs, and be willing to change.

It also requires personal and financial sacrifices, because one parent is home instead of working. “But whether you’re home or making money in the workforce depends on your values and whether your definition of success is measured in dollars,” she noted.

Her initial goal of giving her children more time to spend with their father has been met, and today they all enjoy close relationships.

“Any endeavor worth pursuing will have its share of challenges, and there will be good days and bad days,” she explained. “But in the end, even with the kids squabbling, the uncertainty and worry about whether I’m doing the right thing or if I’m doing enough; and the sacrifices in health, time, energy, money, and sometimes my sanity … I still believe that homeschooling is worth the sacrifice.”

Teen Sofia Iacobucci agrees. “I left homeschooling because I wanted to try something new, and a lot of homeschool friends were going to public school,” she said. “But it was a big change. I liked the freedom we had at home. We had a say in what we wanted to learn instead of being told what we had to do and it allowed me to take my education into my own hands and become independent.”

Which is indeed the goal of every parent; to raise a well-rounded, happy and independent child.

Those managing the

Those managing the

Already, many have come to take in the Kern Center, he explained, adding that he is one of many who will give tours to those representing institutions such as Yale Divinity School, which is contemplating a village of buildings with similar credentials.

Already, many have come to take in the Kern Center, he explained, adding that he is one of many who will give tours to those representing institutions such as Yale Divinity School, which is contemplating a village of buildings with similar credentials.