Healthcare Heroes

Nurse Manager, VA Central Western Massachusetts Healthcare System

Her Work Caring for Veterans Is Grounded in a Sense of Mission

After a decade and a half in the nursing profession, Julie Lefer Quick was looking for a change, and found one at the Veterans Administration’s (VA) outpatient clinic in Springfield.

She also found a level of passion and mission-driven commitment she hadn’t experienced before.

“I can honestly say that I’ve never seen nurses more dedicated to their population; I feel the dedication,” she said. And so do the patients. “Last week, a nurse forwarded me an email that she received from one of her veterans’ caregivers about what great care she took of that veteran, just going above and beyond. And she said, ‘I love my job.’

“Every one of the nurses who works with the VA goes above and beyond every single day,” Lefer Quick added. “And it’s really wonderful to be a part of that, serving such a deserving population.”

She started at the VA in July 2018 as a primary-care nurse. Before that, she worked for a pediatrician in solo practice, including as practice manager, for two and a half years, followed by more than 11 years in the Springfield Public Schools.

“When my son went off to college, I thought, ‘now is a great time to try something new, get back into primary care.’ So that’s when I got the job at the VA.”

When they hear mention of the VA Central Western Massachusetts Healthcare System, most people think of the hospital in Leeds, which houses services ranging from inpatient psychiatric mental-health and substance-misuse treatment to primary care; from rehabilitation to specialties like orthopedics, radiology, cardiology, and many others.

“Every one of the nurses who works with the VA goes above and beyond every single day. And it’s really wonderful to be a part of that, serving such a deserving population.”

“And we also have five community-based outpatient clinics, where we primarily do primary care and then, depending on the clinic, some specialties to support the veterans,” she explained, noting that these are located in Springfield, Fitchburg, Greenfield, Pittsfield, and Worcester. “In Springfield, we have a very large mental-health department, and we also have a small lab, physical therapy, a registered dietitian, a clinical pharmacy, and what’s called home-based primary care.”

As it happens, Lefer Quick loves primary care, and missed that during her years working in the schools. “I had missed the ongoing, deep relationships with patients and their families.”

So, with her son graduating from the school system, she craved a return to care in a medical-office setting, and happened to meet some VA nurses at a Learn to Row event through the Pioneer Valley Riverfront Club in Springfield, where her husband, Ben Quick, is executive director.

“They were like, ‘oh you should come work at the VA,’” she recalled. So she did — and, not surprisingly, she loved the work. Which is why she was hesitant to take the position of nurse manager when it became available last October.

“I wasn’t really sure I wanted to be a nurse manager. I love taking care of my patients. I love working with my team in the VA,” she said. “Nationwide, we practice a primary-care delivery system called the PACT model, which stands for patient-aligned care team. So there’s one provider, one RN, one LPN, and one admin; it’s sort of like a mini-practice within a group practice.

“We always see the same patients, and I had a great team that I worked with,” she went on. “It’s a good model for the patients; they really love it. So I didn’t want to leave my team or my patients.”

But a mentor encouraged her to try something new, and she accepted the detail.

“As a PACT RN, I was providing direct patient care and education, working with my team to meet population health-management goals, such as certain levels of control for diabetes or hypertension. And now I work for the other PACT nurses, supporting them in their practice.”

The busy community-based outpatient clinic in Springfield is one of five operated by the VA in Western and Central Mass.

As nurse manager for two clinics — Springfield and Greenfield — she currently supervises 23 LPNs and RNs, with about three more to be hired soon. And she quickly found she could apply her passion for care in this overseeing role.

“In the VA, we have a unique understanding of the military culture that other providers in the community don’t necessarily have,” she said. “It’s a very sad truth that a lot of our veterans have emotional issues when they come back, but we are on the cutting edge of all types of mental-health treatment modalities and therapeutic options, and we also have the support of Congress — it’s a single-payer system, and we don’t have to be bogged down by some of the stuff that community providers have to deal with. So we, as nurses and providers, can really focus on our veterans and come up with innovative ways to care for them.”

A Passion for Patients

A quick look at the typically full parking lot at the VA’s Springfield CBOC, which stands for community-based outpatient clinic, testifies to the need for the services it provides, from laboratory and pharmacy to primary care and behavioral health.

“From what I have learned as the spouse of a VA nurse manager, it seems that, while most of these workers could get paid more elsewhere, they stay with the VA because they are passionate about caring for our veterans, and they are energetic about supporting each other in this difficult, important work,” Ben Quick wrote in nominating his wife for the Healthcare Hero recognition.

Yet, nursing wasn’t her first career. After graduating from college, she worked briefly in human resources, found she didn’t like that career, and went back to school for a nursing degree.

“Coming out of nursing school a little bit older than the typical students, I kind of took the first job that I could get,” she recalled. “I had a small child, so I didn’t want to work hospital hours, even though I loved the idea of being in the hospital, so I went to work for a pediatrician.”

Which surprised her, considering that her nursing-school rotations caring for youngsters tended to make her cry because she didn’t want to see them hurt or sick.

“I think there’s more of an awareness of mental-health needs in general in healthcare right now. And certainly, veterans who have seen combat are going to need support afterward. So that’s part of our mission.”

But as a pediatric nurse, “I loved seeing the kids grow over the years, seeing new babies born into families, working with parents on all kinds of different diagnoses to help their kids,” she recalled, and her next move was born of wanting to keep caring for children. “Working in the public schools was a way to be available for my son while also reaching a big population of kids. And I loved it.”

So Lefer Quick felt torn about leaving pediatric care for the VA.

“I remember leaving the public-school job for this, and I was very, very excited, but I had this moment of, ‘oh my gosh, am I doing the right thing?’ I said to one of my friends, ‘but I love my kids so much here.’ And she said, ‘you’ll find new patients in a while.’ And I did.”

In doing so, she’s taken to heart Abraham Lincoln’s famous quote that the VA — established 65 years after he uttered it — has adopted as a sort of mission: “to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow, and his orphan.”

“One of the things that almost kept me from accepting the detail to nurse manager was all my patients,” she said, but she understands that all her roles have been supportive in some way: “supporting kids and their families, supporting students at school to be optimally healthy and ready to learn, supporting our veterans, and now supporting the nurses who provide that care to veterans.”

Some of that care is behavioral and substance-related. “We recognize the need for that integrated care for our veterans. I think there’s more of an awareness of mental-health needs in general in healthcare right now,” she noted. “And certainly, veterans who have seen combat are going to need support afterward. So that’s part of our mission.”

She said the VA has felt the strain of a nationwide nursing shortage as much as any other facility, but added that the nurses who take jobs there value the mission President Lincoln put forward — and many are veterans themselves, or come from a strong military family, or are drawn for some other reason to caring for a veteran population.

“That was how I talked myself into the manager position. I thought, ‘well, if I can be a manager with my background, already doing this job, I can support these nurses, which ultimately provides better care for the veterans.’ So I’m not just doing it for my team; I’m helping every single team.”

The COVID pandemic posed challenges across the spectrum of healthcare, but Lefer Quick said the VA was uncommonly prepared for it, as it had already implemented a remote monitoring platform called VA Video Connect, so VA facilities were able to pivot to virtual appointments more quickly than other organizations.

For instance, before the pandemic, “I had a patient who needed monthly monitoring for medication he was on, and he liked to travel. So we would do video visits, and we would have a set appointment to do the follow-up for his medication, wherever he was. So we already all knew how to use this,” she recalled.

And when COVID struck, “we very quickly pivoted to using video for several months, almost exclusively. A lot of our patients did not want to come to the clinic. Nobody wanted to go anywhere. And we already had this in place.”

Their concerns were warranted, as the pandemic hit the elderly population hard in the earliest days of the pandemic. “As you can imagine, a large percentage of the VA population is elderly. I had a father-son set of patients — and the son was 74. So a lot of them, being elderly and therefore immunocompromised, were scared, but the VA already had this amazing video platform, and we had already trained everybody how to use it.”

Meanwhile, “the nurses that I worked with were coming up with great ways to rotate the staff through the clinic so that we could spread out more to allow for that social distancing and masking in a more comfortable way,” Lefer Quick explained. “And we took on new providers and new nurses, even during the pandemic. We didn’t slow down much.”

Cutting-edge Care

In his nomination, Ben Quick boiled his pitch down to three thoughts: the VA’s quality of care is second to none, downtown Springfield has a busy medical practice devoted to healing America’s heroes, and the workers there are humble, passionate, professional patriots. “That’s a Healthcare Hero story that everyone needs to hear,” he wrote.

And now they will.

“The VA is the best employer I’ve ever had in my entire life,” Lefer Quick said. “They value creativity and innovation, and they support us to explore that.

“We really are on the cutting edge,” she added. “The people I work with are doing amazing things and love to be there. No matter where they are, in Springfield or any other part of this country, if someone is eligible for VA care, they really ought to look into it.” n

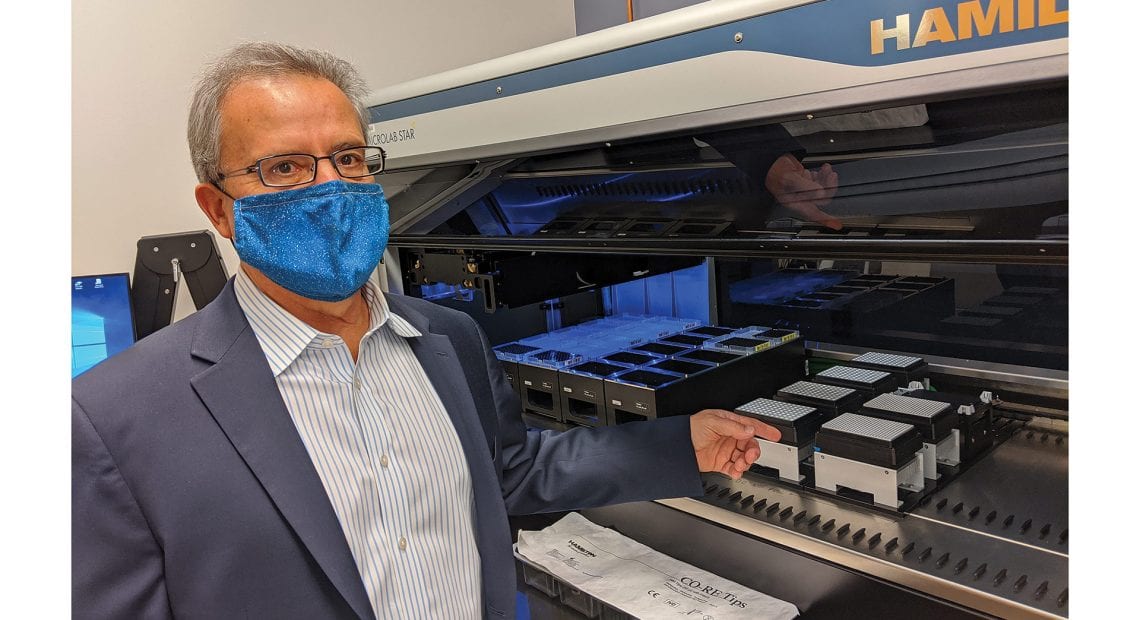

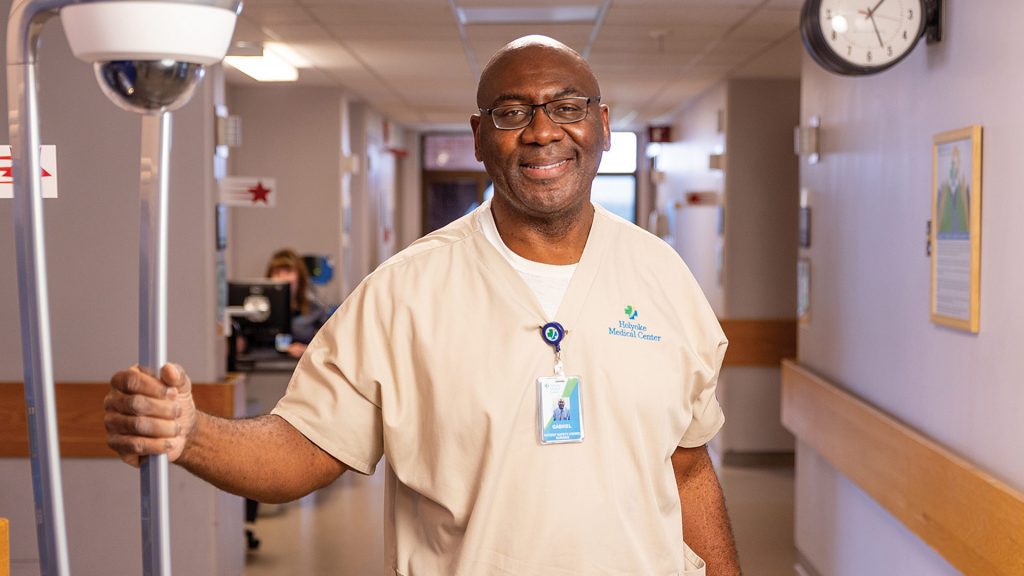

Patient Safety Associates, Holyoke Medical Center

Their Lifesaving Actions Shine a Light on a New Position at HMC

Gabriel Mokwuah

Joel Brito

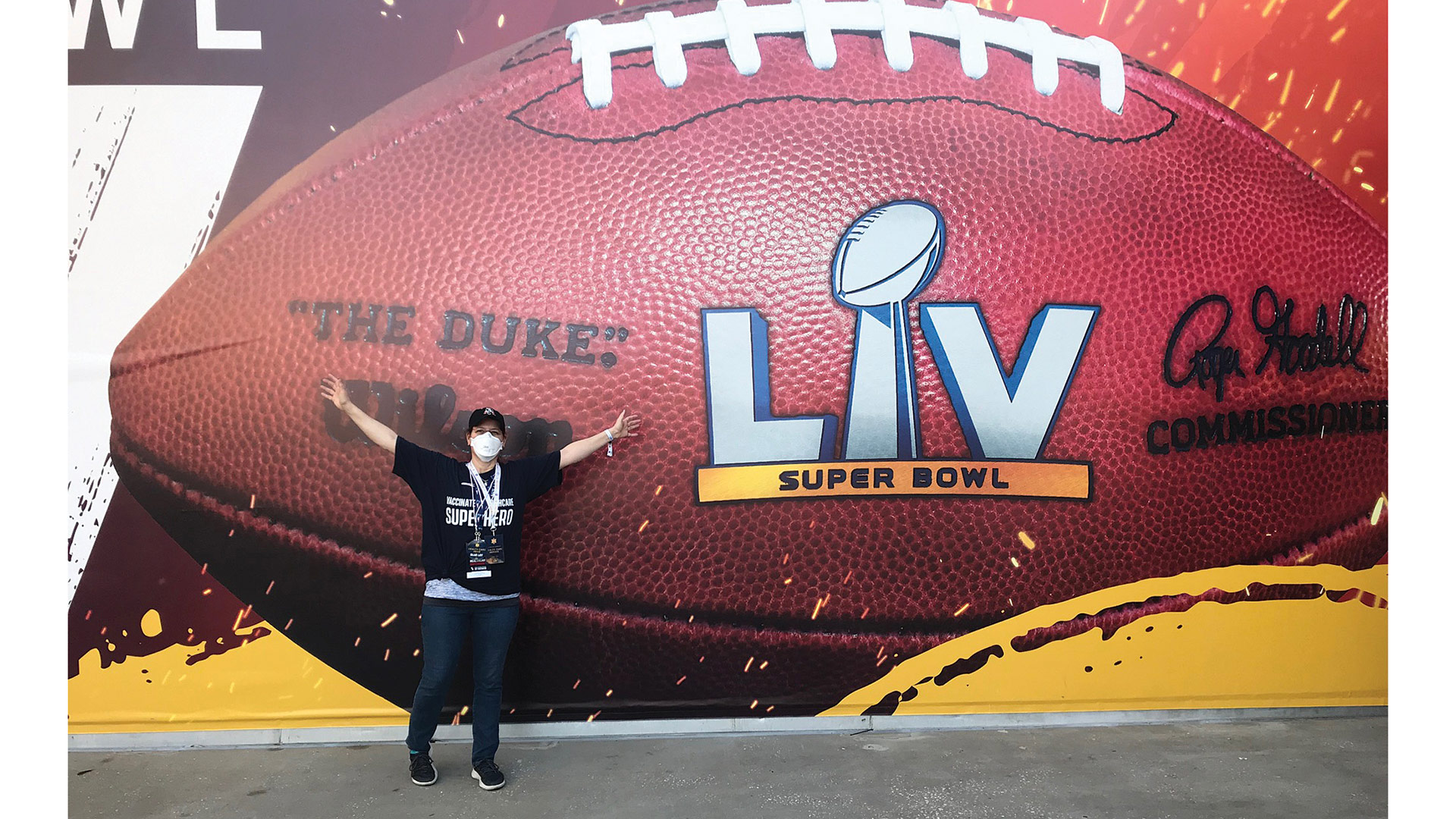

When Gabe Mokwuah came to this country from Nigeria when he was 12 and heard people talking about ‘football,’ he thought about the sport played with a round ball that athletes try to kick into a net.

The other football, the one that is much more popular in this country? He didn’t know anything about it, and didn’t really want to know anything about it.

But that didn’t stop the football coach at his New York City high school from trying to convince the large, fast, and very athletic Mokwuah to try out for the team. Eventually, and we’re simplifying things here, he succeeded in those efforts. But even then, Mokwuah wasn’t really interested in the sport.

It wasn’t until he started hearing the word ‘scholarship’ and came to understand that football could be a means to an end — a college education and a ticket out of a high-crime area on Staten Island — that he began to really take it seriously.

Fast-forwarding through the next several years, Mokwuah did attend and graduate from American International College, while also playing defensive end and linebacker — so well, in fact, that he was drafted by the Green Bay Packers in the 11th round in 1992 (they only have seven rounds today).

He played in two exhibition games, was cut, tried to catch on with a few other teams, didn’t, and wound up working as a court officer at the Hampden County Jail and House of Correction, a job from which he retired several years ago.

All that adds up to just one of the intriguing backstories that can be told by those now working as patient safety associates (PSAs), or, in his case, patient safety coordinator, at Holyoke Medical Center (HMC).

Joel Brito has one of his own.

He was working for Hulmes Transportation, taking individuals to medical appointments and daily programs while also volunteering his time to help those with substance-abuse issues when he saw an ad posted on Indeed — Holyoke Medical Center was looking for patient safety associates.

“As soon as I saw it, I jumped on it, and here I am. This has always been my dream — I always wanted to be in the healthcare field,” he said, adding that his ambition is to become a certified nursing assistant.

Others now working as PSAs at HMC have backstories as well. Some are retired or semi-retired CNAs who succeeded in finding work that is rewarding on many levels. Others are getting started down the road to careers in healthcare and have taken this entry-level position to explore options and find out if healthcare is for them. Some are in pharmacy programs. One is studying for her MBA.

The PSA position is relatively new to HMC, and healthcare in general, and it represents an imaginative and innovative step forward from the ‘sitter’ or ‘patient observer’ role seen in most hospitals, said Margaret-Ann Azzaro, vice president of Patient Care Services and chief Nursing officer at HMC.

“As soon as I saw it, I jumped on it, and here I am. This has always been my dream — I always wanted to be in the healthcare field.”

Elaborating, she said the role involves not merely sitting with an at-risk patient, but engaging with them as a well, a position that brings more value to the patients and the hospital, but also those who assume that role.

“We thought, ‘let’s come up with a safety role to empower people to not only keep these patients safe, but engage with them as well,” she said. “We don’t have sitters here; we don’t have observers here — we have patient safety associates, and the idea is to give them some education and tools to enrich the experience while they’re sitting with a patient.”

Mokwuah and Brito embody the motivations behind the PSA position and also just how vital these individuals are — to a hospital, to the patients they serve, to initiatives to reduce falls and improve overall patient safety, and, sometimes, much more.

Indeed, both have been credited with saving lives in recent months — Mokwuah in April, by seeing something while in the virtual monitoring room and immediately calling for a team member to check on the patient, and Brito in July for performing the Heimlich maneuver on a patient he heard making sounds of distress while he was sitting with another patient. (More on both episodes later).

Both men were named employee of the month for their respective actions. That’s certainly an honor, and in October, they’ll be receiving another one: Healthcare Hero.

Not on Their Watch

There are actually three distinct roles within the PSA position, and individuals with that title handle all three on a rotating basis, noted Brian Toia, Nursing director of the ICU, RN float pool, and patient safety associates, adding that teamwork is what makes this innovative program so effective.

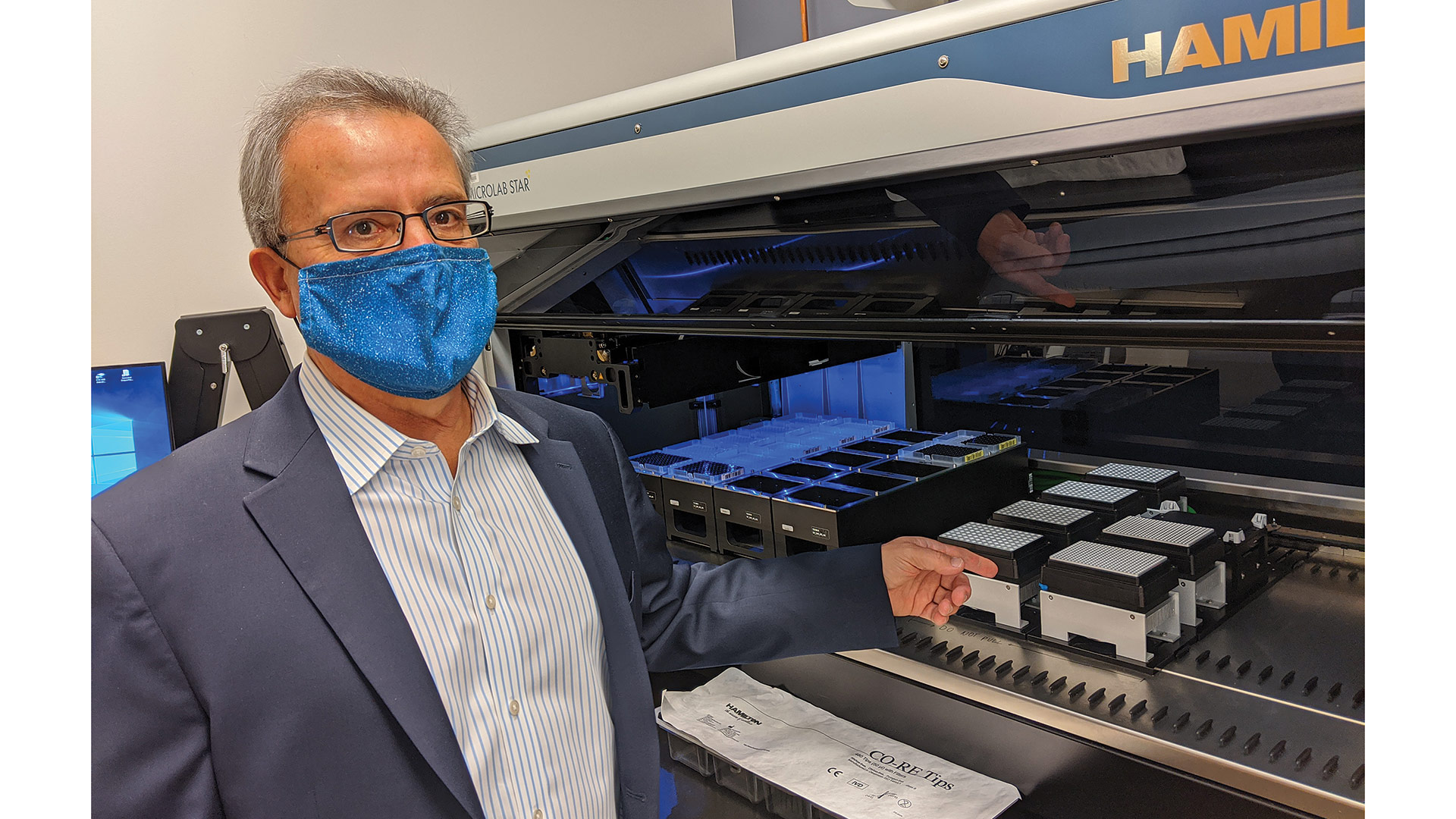

The first role involves one-on-one direct care — staying within arm’s length of a patient with a high safety risk, including those susceptible to falls, patients with dementia, and those who might be suicide risks. The second involves virtual monitoring. Utilizing a camera system placed in rooms of patients with potential safety risks, PSAs working in the virtual monitoring room can keep tabs on up to 12 patients at once.

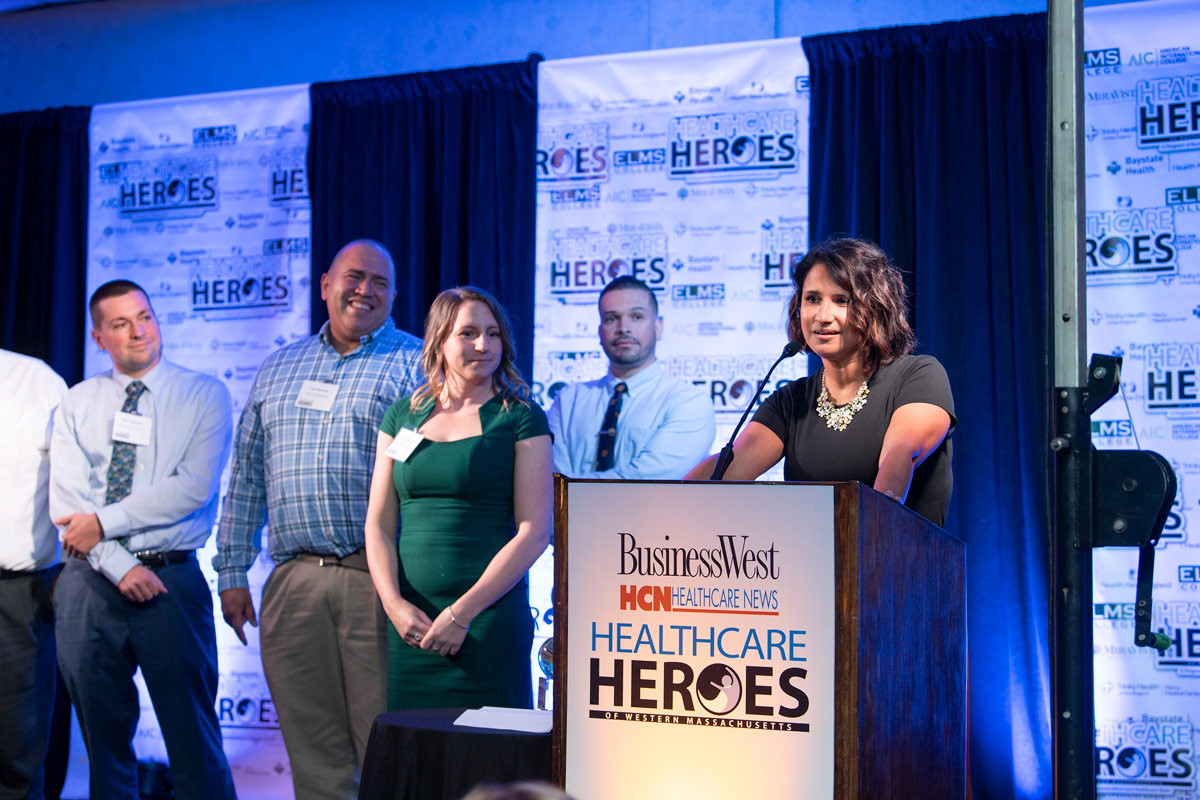

From left, Margaret-Ann Azzaro, Joel Brito, Gabe Mokwuah, and Brian Toia.

The third role is what those at HMC call a ‘rounder,’ one person dedicated to a unit who will frequently check on patients, respond to virtual monitoring calls, and also answer patient calls for assistance.

When asked which role he liked the most, Brito didn’t hesitate. “I like being a rounder. I love that it’s a non-stop job.”

But all these roles are vital to the overall mission of keeping at-risk patients safe, said Mokwuah, who coordinates the department and makes the daily assignments.

Before he talked about the PSAs and what they do, he put matters in their proper perspective. “The real heroes are the nurses, the doctors, and the administrators. And they have given us support for this program to take off. Our job is to keep people safe, and our program saves lives — we’ve proven that over and over again.”

“We thought, ‘let’s come up with a safety role to empower people to not only keep these patients safe, but engage with them as well.’”

Azzaro agreed, emphasizing, again, that PSAs are far more than the ‘sitters’ of years ago. These are individuals who can, and do, watch over patients. But they also engage them and help “enrich the experience,” as she put it, while offering some examples.

“We gave them dementia and Alzheimer’s education,” she explained, noting that this, like other aspects of the program, is fairly unique within the industry. “There are certain ways in which we can engage with patients that have dementia, that have Alzheimer’s. One thing that doesn’t help them is to not be stimulated. So the PSAs can read to them, they can play games with them, they can have conversations with them, they can read a book to them, they can put something on the TV or iPad and have the patient watch it with them.”

And while engaging with these patients, or watching them on the monitor, or coming to their assistance as a rounder, the PSAs are ultimately keeping them safe, said Azzaro, noting that there has been a measurable decrease in the number of falls recorded at HMC since the start of the program.

Changing Lives, Saving Lives

As he talked with BusinessWest outside the monitoring room, Mokwuah said the facility boasts a split screen showing more than a half-dozen patients in their beds. At this moment in time, all was quiet and normal.

That was not the case one afternoon back in April, when, while watching that same monitor, he noticed a patient that did not appear well, was acting differently, and had a noticeable status change.

He called for a rounder to immediately check on the patient, who, as it turned out, was experiencing a significant medical event, was unresponsive, and had no pulse. Staff quickly began performing basic life support, followed by advanced cardiovascular life support. After two rounds of CPR and cardiac medications, the patient’s own breathing and heartbeat returned.

Joel Brito (left) and Gabe Mokwuah have both been credited with saving patients’ lives in recent months.

Staff Photo

Joel Rivas, director of Nursing Medical-Telemetry, who nominated Mokwuah for employee of the month, said at the time, “it is my professional opinion that, had the patient’s change in condition not been identified as early as it was, by Gabriel, we would not have had the positive outcome that we had.”

Similar things were said after another incident in early July, when Brito again showed the importance of HMC’s innovative PSA program.

He was serving as a rounder and sitting with a patient when another team member came in to provide patient care. During that time, Brito overheard a patient from another room making sounds of distress. Confirming that his one-on-one patient was safe and in the care of another team member, he stepped into the next room to check on what he’d heard.

“In the beginning, I didn’t pay too much attention to it, but something told me to get up and check that room, and when I did, I was really surprised because the lady was essentially purple,” he said, adding that he quickly positioned himself to perform the Heimlich maneuver and helped to dislodge the obstruction in the patient’s airway.

“This is a job where you have to be humble, you need to have some empathy, and you have to love people. That’s something my mom and my family instilled in me growing up, so I try to live my life that way and help people. This job gives me the opportunity to do that.”

Like Mokwuah, Brito was credited with saving a patient’s life, said Toia, adding that, had it not been for establishment of the rounder’s role within the PSA program, it’s unlikely that someone would have been able to respond as quickly to the situation as he did.

Looking back, Brito said he relied on his instincts and his training, and was thankful to be in a position where he could help people and make a difference in their lives — the most gratifying aspects of the PSA position.

Mokwuah said essentially the same thing.

“This is a job where you have to be humble, you need to have some empathy, and you have to love people,” he said. “That’s something my mom and my family instilled in me growing up, so I try to live my life that way and help people. This job gives me the opportunity to do that.”

Big-game Players

Gabe Mokwuah didn’t get to be a hero on the gridiron, at least at the pro level. But his life and career, especially this latest chapter, show that our heroes come from all walks of life. And they take all kinds of titles.

Patient safety associate is a relatively new one at Holyoke Medical Center, an innovative initiative that is helping to prevent falls, improve overall safety, and, as these cases show, save lives.

Mokwuah was right when he said that doctors, nurses, and administrators are heroes. But so are those with badges that read ‘patient safety associate,’ especially these two lifesavers and Healthcare Heroes.

Clinical Psychologist; Assistant Professor of Graduate Psychology, Bay Path University

She Impacts Lives — and the Next Generation of Mental-health Professionals — for the Better

It’s not easy to cover everything Kristina Hallett has done in her wide-ranging career in one story. At least, not cover it in a way that fully conveys her impact.

Her past titles convey some of it. Director of Brightside Counseling Associates and then director of Children’s Services at Providence Behavioral Health Hospital, both in Holyoke. Supervising psychologist at Osborn Correctional Institute in Somers, Conn. Director of Psychology Internship Training at River Valley Services in Middletown, Conn. And currently, associate professor in Graduate Psycholology and director of Clinical Training at Bay Path University.

Oh, and she’s maintained a private psychotherapy practice in Suffield, Conn. for the past quarter-century.

There are some common threads.

“Dr. Hallett’s career spans over 25 years, during which she provided invaluable psychotherapy, consultation, and supervision to medical and mental-health professionals, addressing myriad relationship and major life issues. Her expertise in complex trauma and dissociative disorders is instrumental in supporting and empowering those facing significant psychological challenges,” wrote Crystal Neuhauser, vice president of Institutional Advancement at Bay Path, one of three people who nominated Hallett as a Healthcare Hero.

Just as importantly, “she is a guiding influence in shaping the next generation of mental-health practitioners. Her commitment to education and mentorship showcases her passion for instilling excellence, compassion, and cultural competence in students. She is especially passionate about guiding under-represented caregivers into the profession to help underserved communities see themselves in their mental-health professionals.”

That’s a mouthful, but it’s important to understand the generational impact of Hallett’s work — not only helping people move through often-severe challenges and trauma toward a happier, healthier, more fulfilling life (which she accomplishes as a teacher, therapist, executive coach, author, speaker, podcaster, and more), but she’s helping to raise up the next wave of mental-health professionals to do the same, at a time when the needs are great.

“When we’re talking about mental health, it’s about connection, and there are different ways to make a connection. And having a role model who look like you and who understands you is really important.”

“I’m just ecstatic about our program,” she said of her role at Bay Path, where she started teaching in 2015. “When I came, we had maybe 50 students. Right now, in our program, we have 280-plus students. This summer, they did a 100-hour practicum with us before their 600-hour internship out in the community. We had 62 students in practicum this summer, which is a logistical challenge, but we’re really able to help shape them, educate them, and give tools and resources to the next generation.”

Kristina Hallett’s books have delved into topics ranging from relationships to banishing burnout.

Staff Photo

Meanwhile, Hallett’s bestselling books, Own Best Friend: Eight Steps to a Life of Purpose, Passion, and Ease and Be Awesome! Banish Burnout: Create Motivation from the Inside Out, inspire personal growth and empowerment, while a co-authored workbook titled Trauma Treatment Toolbox for Teens is a resource for young people facing trauma-related challenges, and her contribution as a co-author to Millennials’ Guide to Relationships: Happy and Healthy Relationships are Not a Myth! reflects her commitment to enhancing the lives of diverse populations.

As an executive coach, she helps participants find lasting change in the areas of burnout, stress, motivation, and self-confidence. And her podcast, “Be Awesome: Celebrating Mental Health and Wellness,” provides hope and guidance to listeners, fostering an environment where seeking help and prioritizing mental health is normalized.

As noted, it’s a lot to take in, but Hallett is energized by the opportunity to impact so many lives in so many different ways. The opportunity, in fact, to be a Healthcare Hero.

Connected to Kids

Hallett’s private practice offers individual and family treatment, with some intriguing specialty areas, including psychotherapy for medical and mental-health professionals, military personnel, and first responders; substance abuse; mood disorders; LGBTQ clients; trauma recovery; and treatment of complex trauma and dissociative disorders.

It’s a far cry from her earliest goal in life, which was to be a pediatrician.

At Wellesley College, where she was a biology major in a pre-med program, she took a psychology course “for fun” — and found the topic interesting, so she added a double major in psychology. “My professors were like, ‘oh, you should go into psychology.’ And I said, ‘no, no, no, I’m going to be a pediatrician … right?’”

During her senior year, as she took her medical college admissions tests, Hallett found herself in an interview, being asked, ‘why do you want to go to medical school?’ And something clicked.

“I had this experience where my mouth kept talking, but a part of my brain said, ‘yeah, why do you want to go to medical school?’”

Her answer was to enroll at UMass Amherst — in a graduate psychology program.

That’s not to say she wouldn’t work with children, adolescents, and families, though. At her earliest career stops, she had plenty of opportunities for that, from her stint as regional program supervisor for the Key Program in Springfield from 1991 to 1995 to her roles with Brightside Counseling Associates from 1996 to 1998 and Providence Behavioral Health Hospital from 1998 to 2003.

“I loved the idea of working with adolescents because, while I was young, still in my 20s, I felt like they’re ripe for change; you can be honest with them … it’s a very real interaction, while adults are just stuck in their ways,” she said, adding quickly, “I don’t think that way anymore.”

That’s because she’s had plenty of experience working with clients of all ages. In fact, her next stops — at Osborn Correctional Institution from 2003 to 2005 and River Valley Services from 2005 to 2015 — broadened her experience dramatically.

Kristina Hallett’s office in Suffield, Conn. is filled with photos, artwork, and mementos from her interactions with patients.

Staff Photo

“So the first half of my career was children and adolescents, but really centered on adolescents,” she said. “And it’s unusual for someone to be running an outpatient mental-health clinic and running inpatient children’s services, and then working in a prison.” At the time, she added, Osborn housed 2,000 male inmates and also arranged schedules for mental-health workers for some other local prisons.

Years later, while working at River Valley, Hallett had a yen to get into teaching, so she joined Bay Path as an adjunct professor in 2015, which quickly led to part-time work and then a full-time opportunity. It sure beat the commute from Suffield to Middletown, but there were other, more important reasons to make the jump.

“Bay Path had just started its clinical mental-health counseling program, and they were going to expand. And I thought, ‘yeah, I’m ready to do this full-time.’”

Her first title was coordinator of clinical training, which became director of clinical training. And this past spring, when the program director left, she took over that role.

“I’ve been responsible for bringing in a lot of faculty over the last few years, and this summer alone, I brought in four faculty who are former graduates of our program, all coming from different perspectives,” she told BusinessWest. “I like to bring back our graduates because they know the program, and we want to support them in their career. I’m trying to create a pathway for our students, post-graduation, to continue their own growth and learning.”

A couple years ago, Hallett’s department procured a behavioral-health workforce and education training grant through the Health Resources and Services Administration, to support and build up the young mental-health workforce, but also to better integrate these professionals into medical settings.

“So, you have a medical office with physicians, and then you have an embedded clinician,” she explained. “You come in for your annual physical, maybe you’ve been feeling a little down, and your physician says, ‘oh, you know what, I’ve got Stacy here who can maybe talk to you about that.’ And Stacy talks to you and sees if there are resources available to help you — therapy or whatever. So that’s a newer model that’s beginning to happen, which is great.

“It’s always about increasing access, because there’s a huge mental-health crisis, a huge need, a huge waiting list,” Hallett went on. “So anything to increase the workforce is great.”

In 2023, the third year of the four-year grant, Bay Path was able to fund 36 students to the tune of $10,000 each. “So 36 students are working full-time, many have families, and they’re still trying to get a master’s degree and go into the field. As you can imagine, it’s really hard to do all that and then work 600 hours as a clinician. So the $10,000 is phenomenal.”

She recently applied for another grant, with a bigger stipend, for students going through their internships and want to work in community-based clinics, either with services from the Department of Mental Health or a majority MassHealth clientele. “So the people who need the services are going to get good services,” she said, while, again, cultivating the next generation of professionals. “I am so excited about it.”

Heart of a Teacher

It was Hallett’s love for educating people, in fact, that led her to finding other ways to communicate.

“I love what I do one-to-one, and I love teaching. So what other ways do I have to make an impact with things that people really need to know?” she said. “The podcast and the books and the speaking are just ways to share messages and really say, ‘there are things that we can do to help ourselves, to feel a sense of agency, even when the world is sort of going crazy around us, and when there are really difficult challenges that we don’t necessarily have any control over.”

So much of her work, she said, has been with community-based organizations because she cares about access to mental health, especially for the underprivileged and underserviced. “I want to support and encourage an increase in a truly diverse workforce because that’s who we are. People need to see people like themselves. It’s not that they can never talk to people with differences; of course they can. But when we’re talking about mental health, it’s about connection, and there are different ways to make a connection. And having a role model who look like you and who understands you is really important.”

As for her decades of work with stress and trauma, in particular her work with clients from the military and first-responder communities, it started early on, working with adolescents in difficult situations.

“There are horrific things that humans do to each other that are certainly hard to live through,” she said. “They’re hard to hear about, and they’re hard to know. So I try to counteract that darkness with some kind of support. People who have gone through really horrible things deserve someone to stand in the witness of that.”

For a while, in the pre-COVID years, Hallett said, she was primarily working with medical and mental-health professionals in her practice. “These are small communities; it’s hard to find providers who work with providers. So that just sort of evolved. I had already started working with veterans and first responders, and then COVID hit, and that was a time when there was so much need.”

She no longer works with teens, and the goal for her adult clients is to get them back out living their lives and doing the work that’s meaningful to them. “But if something comes up at another point in time where something new has happened, you can come back. We create a relationship that allows you to come and go. I’m always working to create these longer-term relationships.”

And, not surprisingly, she has applied that passion to her other career at Bay Path, helping to create an advanced trauma certificate in her department.

“As practitioners in the field, we’re always asking, ‘what’s the latest? What’s backed by science? What do people need to know? What do we wish we knew when we were in school? And how do we continuously support the growth of the next generation?’” she said. “Because we need them.” n

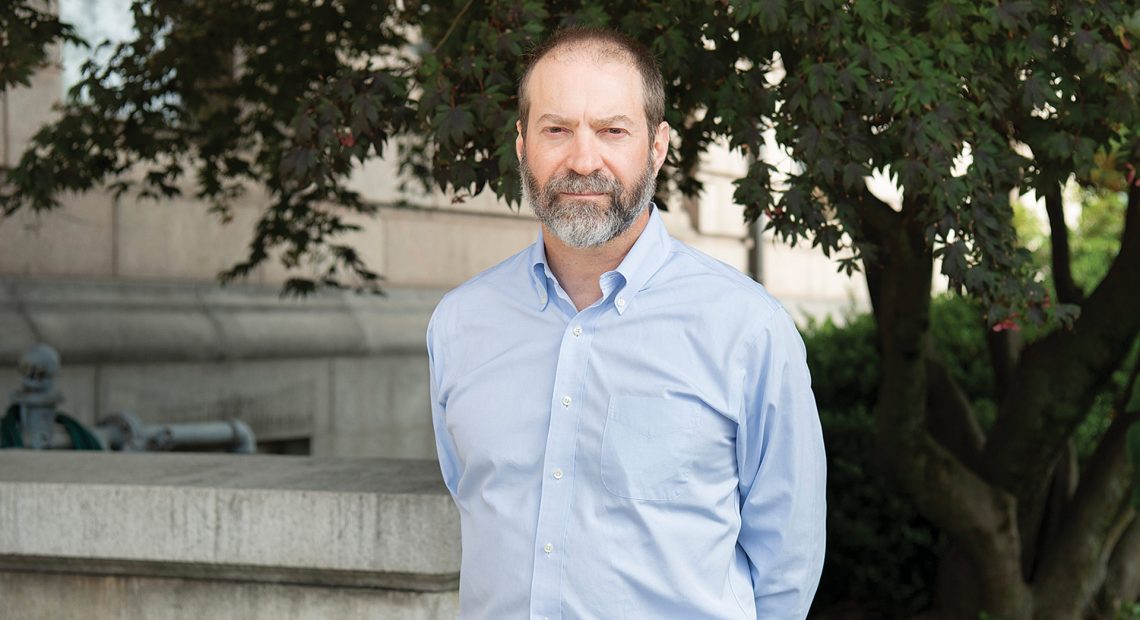

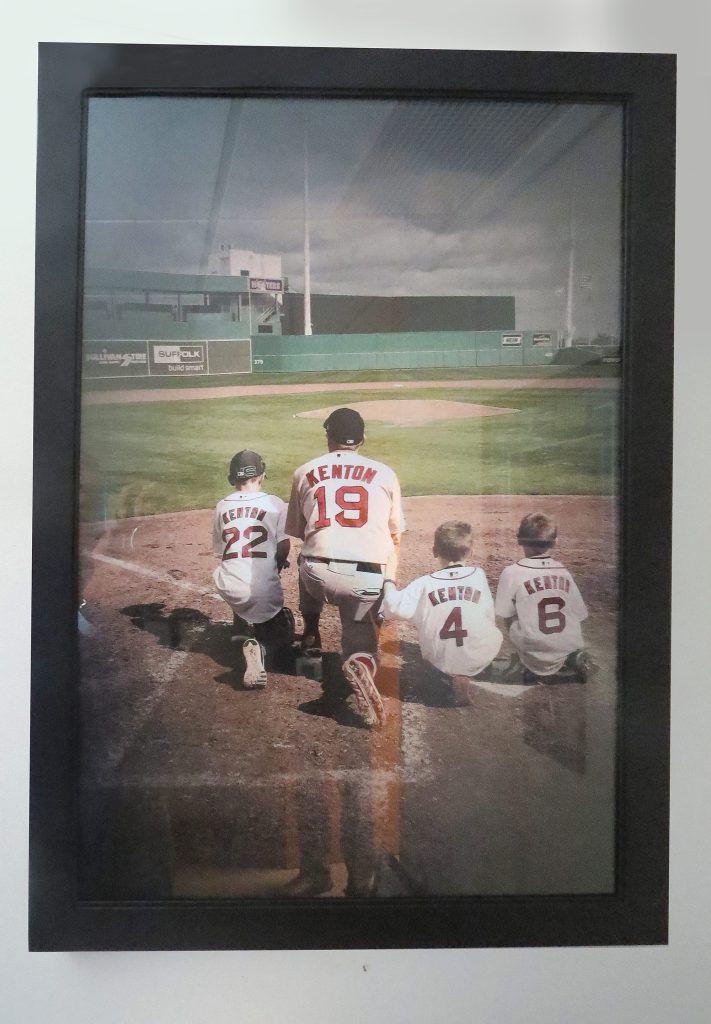

Chief of Emergency Medicine, Mercy Medical Center

He Considers Listening His Strongest, Most Important Talent

As a general rule, physicians working in the emergency room don’t get to know their patients as well as those in primary care or other specialties, who see their patients regularly and over the course of years and, sometimes, decades.

But Dr. Mark Kenton makes it a point to get to know those who come to his ER, the one at Mercy Medical Center. Indeed, he said he always looks to make a connection by listening to each patient and learning about what they are interested in and passionate about.

In addition to making these connections, he tries to get involved and make a difference, in ways that go beyond providing medical care.

“Sometimes, the best medicine you give someone is not actually medication,” he told BusinessWest. “It’s just listening. Everyone has a story.”

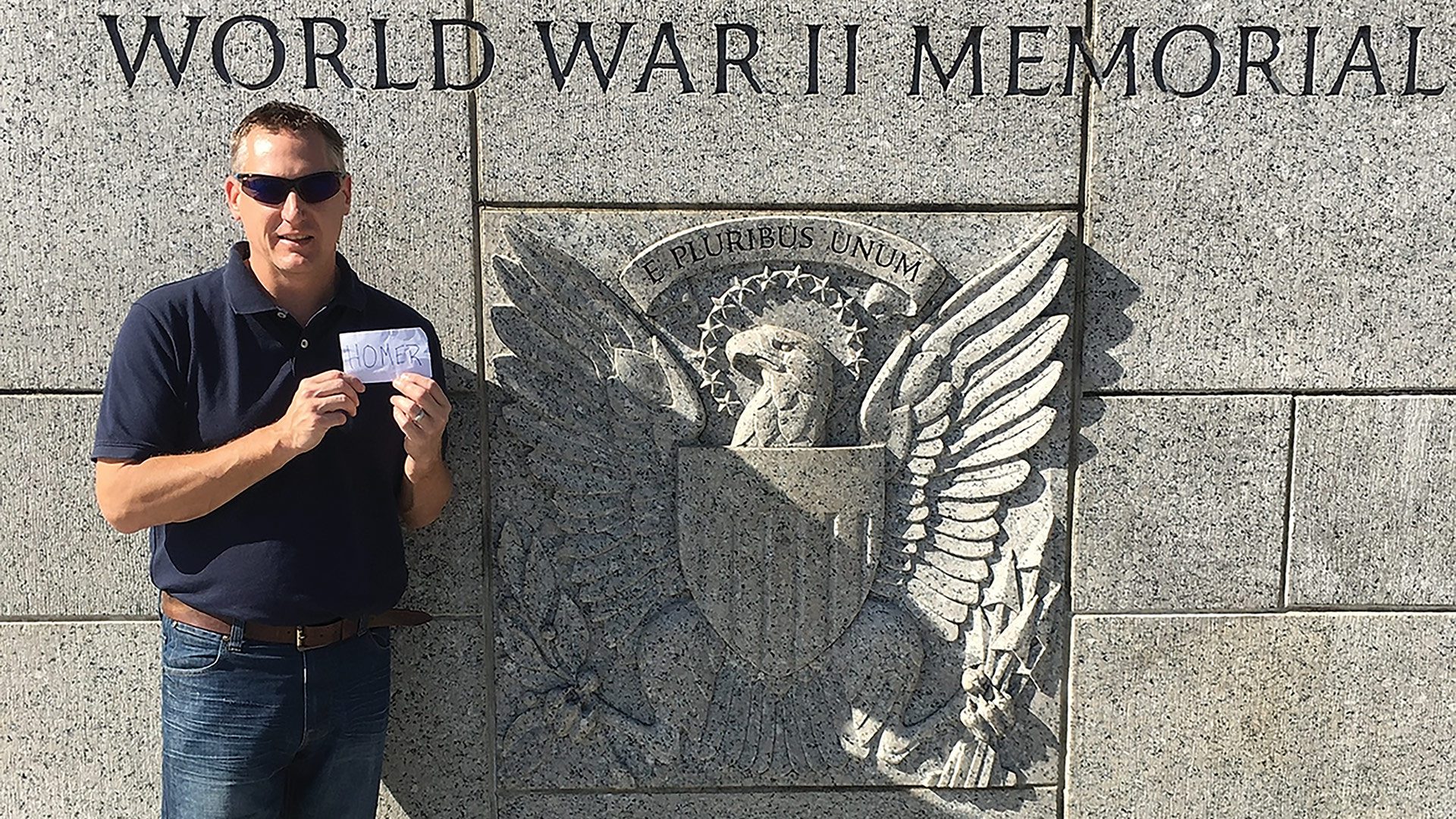

He was listening as one patient, a veteran named Homer who was going into hospice care, expressed regrets about never making it to the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. So Kenton researched the Honor Flights program and worked with the patient’s family to help make arrangements for him to visit the stirring memorial. Later, he received a letter from that family.

“They said he died two weeks before he was scheduled to go, but he died knowing that he was going, and it meant a lot to him,” Kenton recalled. “That stuck with me.”

He was also listening to another patient who was near the end of his battle with cancer and came to understand that the two shared a love of baseball and the Red Sox. Kenton arranged a phone call to the patient from former catcher Rich Gedman, whom Kenton had come to know well from his participation in Red Sox fantasy camps.

“Sometimes, the best medicine you give someone is not actually medication. It’s just listening. Everyone has a story.”

“He said, ‘I can’t believe Rich Gedman actually called me,’” Kenton recalled, adding that the conversation had a lasting impact.

This ability to listen, and act on what he hears, is one of many traits that has made Kenton a Healthcare Hero for 2023 in the Healthcare Administration category — annually one of the most competitive categories within the program.

He stood out amid a number of others nominated for the award for his ability to act upon what’s heard — in a variety of different settings — and generate needed dialogue, which has sometimes led to real change.

This includes the ER at Mercy, where he has worked with others to improve flow, shorten wait times, and reduce the number of patients who leave the ER without being seen, battles that have become even more difficult amid critical shortages of trained professionals, especially nurses.

One of Dr. Mark Kenton’s passions is baseball and Red Sox fantasy camps, something that has become a family affair, as in this scene at Jet Blue Park in Florida with his sons (from left) Mark, Davin, and Jacob.

But it also includes the national medical stage, as we’ll see. Indeed, a letter posted on Facebook from Kenton to the CEO of Mylan juxtaposed the CEO’s salary against the sky-high cost of EpiPens and thrust the debate about the rising cost of pharmaceuticals into the national spotlight.

In Massachusetts, Kenton played a strong role in the passage of a bill that would allow EpiPens to be purchased in the same manner as Narcan for municipalities, whereby the state would purchase them at something approaching cost.

Kenton has also advocated for increased protection from workplace violence in hospitals, testifying at the State House after a colleague at Harrington Hospital suffered a near-fatal stabbing. Those efforts have been less successful in generating change — a result he blames on the high cost of measures such as metal detectors — but he continues to push for legislation that might prevent such incidents.

For his ability to listen and effect change — in his ER and many other settings as well — Kenton is certainly worthy to be called a Healthcare Hero.

A Great Run

The art hanging on the walls of Kenton’s office certainly helps tell his story.

Most of the pictures are baseball-themed — he played in college, has attended the Hall of Fame induction ceremonies in Cooperstown since 1981, and has more than 7,000 baseball autographs, by his estimate — including photos from the fantasy camps he’s attended, with his children prominent in many of them.

“I’ve been going for 13 years now, and it’s been a pretty amazing experience,” he said, noting that he’s been on the same field as many Red Sox legends. “Now, it’s more about going back and playing with friends than seeing the Red Sox — but they’ve become friends, too.”

But there’s also a framed photo of the cast members of The Office, a gift from his children. He is a huge fan of the show, and notes with a large dose of pride that he’s met several of the cast members and possesses a suit jacket that Steve Carell wore on the show.

While Kenton spends a good amount of time in this space, his true office, if you will, has always been the ER, and especially the one at Mercy. He arrived there in 2003 and became chief of Emergency Medicine in late 2019, three months before COVID hit and turned the healthcare system, and especially the ER, on its ear.

The trajectory for this career course was set over time, and Kenton believes his passion for helping others began when he watched medical dramas on television with his mother and became captivated with what he saw.

“My mother had cancer as a child; she spent a lot of time in hospitals and always had a fascination with healthcare,” he recalled. “She was always reading medical books, and we watched every show you can think of — Quincy; Trapper John, M.D.; St. Elsewhere; you name it.”

Because of his love for baseball, Kenton initially considered a career as an athletic trainer, since he could combine both his passions, baseball and healthcare, and he attended Springfield College with that goal in mind.

He quickly realized that the life of an athletic trainer did not have a lot of stability. And after working as an EMT, a rewarding but also harrowing experience — “I remember going to shootings and the shooter was still on the loose” — he decided the emergency room was where he wanted to spend his career. He earned his medical degree at Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine, with the goal of completing his residency in Baystate Medical Center’s ER, a path that became reality.

“I hand out my business card to patients, talk to them, and ask, ‘why are you here today?’ I do that as one more check to make we’re not missing something.”

As he talked about working in the ER, Kenton related what he told his students when he served as medical director of the Physician Assistant Program at Springfield College. “I would always say, ‘be a little scared every day when you walk in — never lose that. Have a little fear when you walk in, because you don’t know everything, nor should you know everything. You need to know what your resources are and how to utilize those resources. You also need to know that you’re going to be tested — every day.’”

Safe at Home

These days, most of Kenton’s work is administrative in nature — he does one clinical shift per week — and, summing it up, he said it’s about making this ER as safe, welcoming, efficient, and effective as he can.

It needs to be all of the above because the ER is the “front door to the hospital,” as he put it, and a safety net for many within the community.

“There are so many patients that don’t have primary-care doctors now or don’t have insurance,” he said. “The ER is what they turn to.”

As he works with his team to improve flow, reduce wait times, and improve the ‘leave without being seen’ numbers, Kenton relies on what might be the strongest of his many skills — listening. In fact, he’s in the waiting room every ‘admin’ day talking with not only patients, but their families as well.

“I hand out my business card to patients, talk to them, and ask, ‘why are you here today?’” he said. “I do that as one more check to make we’re not missing something. I tell them that we’re working hard to get people through the system, and we’ll work on getting you through as soon as we can. And then, I listen.”

This brings him back to his comments about how everyone has a story, and it’s important to know and understand that story.

Dr. Mark Kenton holds up a card with the name ‘Homer’ on it at the World War II memorial in Washington, fulfilling, in a way, a dying patient’s desire to visit the memorial.

“You can look at the medical problem, but if you look at them as just a patient, you kind of forget that behind that patient is a person who’s scared, a family that’s scared,” he said. “Some people have lived incredible lives and been very fortunate, and some people have not had very good luck, or they’ve made bad choices, or they haven’t had the opportunities that others have had.

“I’ve taken care of Tuskegee Airmen; I took care of a gentleman who told me he flew on the Enola Gay,” he went on, referencing the famed African-American fighter and bomber pilots who fought in World War II and the B-29 that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. “You learn from those stories.”

While listening, learning, taking care of patients and their families, and improving efficiency in the ER, Kenton has also become an advocate for needed change in healthcare. His open letter to the CEO of Mylan on Facebook was spurred by incidents in his personal and professional life.

Indeed, while on vacation with his family, his son had an allergic reaction to peanuts. He soon learned that a prescription for two EpiPens, the best treatment for anaphylaxis, would cost $600. Fortunately, that prescription was transferred to a pharmacy that would accept his insurance, bringing the cost down to $15.

But he understood that such good fortune would elude others. While working a shift in Mercy’s ED a few months later, he saw two patients suffering from anaphylactic reactions and gave them both EpiPens, knowing they wouldn’t be able to fill the prescriptions going forward because they didn’t have insurance.

His frustration with this matter prompted his letter, which garnered press across the country and a live interview on Fox Business. More importantly, it generated real change, especially in the Bay State. Kenton testified before the state Senate on a bill introduced by former Sen. Eric Lesser to make EpiPens available for purchase by the state, just like Narcan.

Stepping Outside the Box

Two years after Kenton received that letter from the family of that veteran who died before he could get to the World War II memorial, his wife was running in a marathon in D.C., and he made the trip with her.

He wrote Homer’s name on a piece of paper, took pictures of it in various spots at the memorial, and sent them to his family.

“I said, ‘your dad finally made it,’” he told BusinessWest. “From what he told me during that relationship we established in a really short period of time, that brought closure to me, that he made it there.

“There are things you can do beyond providing medication to someone — sometimes you just have to step outside the box a little bit,” he went on, using a baseball term to get his point across.

This ability to forge those relationships, listen to each patient’s and each family’s story, and go well beyond simply providing medication helps explain why Kenton stands out — in his field, in his ER, and in his community. And why he is being recognized as a Healthcare Hero. n

Pediatric Emergency Nurse, Baystate Medical Center

Her Passion for Behavioral Health Has Enhanced Care Across an Entire ER

Ellen Ingraham-Shaw just couldn’t get away from children — even when she thought she wanted to.

And thanks to her leadership and innovative thinking, a lot of kids are better for it today.

“I actually started my career as a kindergarten teacher,” she said, before jumping back in time a little to when her interest in working with children really began.

“Growing up, I was a horseback rider, and I got into teaching younger kids how to horseback ride; that’s how I started working with children and adolescents, including working summer camps when I was in college,” she recalled.

Then she studied early childhood education and psychology at Mount Holyoke College before spending the first five years of her career as a kindergarten teacher.

There, Ingraham-Shaw saw needs that can’t always be addressed in the classroom.

“I worked in Chicopee, and in my classroom, I had a lot of homeless students,” she said. “So I started getting really interested in the socioeconomic status of kids and all the barriers that can really get in the way of how kids learn.

“I was happy, but I didn’t see myself doing it forever,” she continued, “so I went back to school for a second bachelor’s in nursing at UMass Amherst. After that program, I started working at Baystate Medical Center on one of the adult floors. And I just thought I didn’t want to work with kids anymore after feeling kind of burnt out.”

“Especially during the pandemic, the behavioral-health population just kind exploded in our ER. And I just got really passionate about it.”

So when friends asked her whether she wanted to enter pediatrics, she said no — but that feeling eventually thawed, and she applied for a position in Baystate’s pediatric ER. And she fell in love with it, calling it a well-run unit that, she realized early on, had an openness to new ideas and a focus on behavioral health that she would eventually expand in a number of ways.

“Especially during the pandemic, the behavioral-health population just kind exploded in our ER. And I just got really passionate about it,” she said. “And I’m lucky that my managers and my educators on my unit really support us working toward the things we’re interested in. If you want to seek out opportunities to do your own education, they give you opportunity to research.”

Thus began a fruitful career in pediatric emergency care with a focus creating more education and resources around behavioral health.

“I’ve been able to do education on de-escalating patients, just helping with the safety of the staff and the patients. And I think our physical restraint numbers have decreased; we have seen a decrease in having to resort to a restrictive environment with the kids.”

Ingraham-Shaw also worked closely with Pediatric ER Manager Jenn Do Carmo on Narcan take-home kits for the Pediatric Emergency Department. They were talking one day about how Baystate’s adult ED provides take-home kits to their substance-misuse population, but the Pediatric ED had no such process. So they decided to change that. Ingraham-Shaw created an education flier for nurses and doctors, made sure the kits were stocked, and educated every nurse on how to educate patients and families in their use.

“I did some education with our staff on how to identify patients that might be at higher risk,” she explained. “These are patients who come in with an overdose or, unfortunately, we’re seeing a lot of adolescents these days with suicide attempts and self-harm; sometimes they could be opioid-related, sometimes not. But if someone has a past overdose attempt, they’re at a higher risk of potentially overdosing on opioids in the future.

Ellen Ingraham-Shaw says pediatric emergency nurses bring not only care, but large doses of compassion and education to parents.

“So we’re making sure we have Narcan out in the community,” she added. “The nursing job is to help identify the patients that could be at risk, then working with the providers to make sure Narcan gets prescribed.”

Do Carmo, who nominated Ingraham-Shaw, said this program has the potential to save the lives of pediatric patients who overdose on opioids in the community. “Ellen is also going into the community and teaching local schools about the process of administering Narcan,” she wrote. “Ellen is a strong advocate for her patients and is a Healthcare Hero.”

Knowledge Is Power

As another example of thinking — and leading — outside the box, Do Carmo noted that Ingraham-Shaw noticed a gap in education on the care of LGBTQ and transgender patients, and took it upon herself to create educational materials and a PowerPoint presentation on how to care for and support these individuals.

“The entire Emergency Department now provides her representation on transgender education in nursing orientation,” Do Carmo wrote. “This presentation provides a clear understanding of a population in dire need of support and words and ways that help support the care of this population.”

Ingraham-Shaw told BusinessWest that she developed that education on LGBTQ and transgender health for a staff meeting, and the educators in the ED now utilize it as a required part of onboarding training for all emergency-medicine staff at Baystate, not just in the Pediatric ED. “So all of our staff has some level of training in how to be respectful and understanding of patients in our community.”

That aspect of education can be lacking in the training and college programs medical professionals experience entering their careers, she added. “So I think our people are definitely able to support those patients a lot better.”

Providing care that’s not sensitive to that population typically isn’t a problem of malice, but ignorance, she was quick to add. “It’s just people not knowing. And now my unit especially has at least a little baseline of how to be more respectful and understanding of patients.”

Of course, sensitivity to what patients are experiencing comes naturally in a pediatric ER, where the days can be challenging and the situations dire.

“I did some education with our staff on how to identify patients that might be at higher risk. These are patients who come in with an overdose or, unfortunately, we’re seeing a lot of adolescents these days with suicide attempts and self-harm; sometimes they could be opioid-related, sometimes not.”

“One thing I do like about it is that every day is completely different. I think it’s gotten a little bit harder now that I just had my own baby; I’m still adjusting to that,” she said of the toughest cases. “But the majority of what we see is more urgent care, or things likely to be seen in a primary-care setting. Those usually have a happy ending — you help educate the family, you make sure the child is safe, is eating, drinking, breathing, and then they usually get discharged home.”

At the same time, “unfortunately, we do see some really devastating new cancer diagnoses, we see some car accidents, so it’s definitely emotional. I think my co-workers do a really good job of supporting each other through those difficult times. Healthcare can be sad, and I think it’s especially sad when you know something bad happens to a child. And we do a lot of compassion with the families as well; we take care of the whole family, not just the child.”

Again, she comes back to the education aspect of her work, even for things families don’t specifically bring in their kids for, like properly installing car seats.

“When we’re at the triage desk, we first bring the kid in, we make sure they’re safe, and then that’s another point where we can just educate them and do that community health and make sure everyone’s safe by teaching families simple things like car seats.”

Going beyond the basics is how Ingraham-Shaw has really made a difference, though, implementing new ideas in an organization she says is very interested in hearing them.

“My management team is just really open. We have a lot of freedom to do things,” she said, before giving another example in the behavioral-health realm.

“One of my co-workers and I, a few years ago, started a behavioral-health committee. We try to meet monthly, just to talk about what’s going on with the unit, trying to work on different projects,” she explained. “One thing we did was make an informational pamphlet for the families and the patients that come in for behavioral-health issues because the way we treat them is much different than other patients. And sometimes they’re there for a really long time. So we want to do what we can just to support the families a little bit more.”

Do Carmo praised Ingraham-Shaw for identifying barriers in communication and creating a tool that has improved communication between nurses and patients. “Ellen works very closely with the behavioral-health team to ensure the behavioral-health population receives the needed care plans and treatments.”

Long-time Passion

Ingraham-Shaw’s interest in mental health was clear when she first studied psychology in college, but at the time, she couldn’t have predicted how it would become an important aspect of her career.

“When I was looking for jobs, if I didn’t find a teaching job, I was looking for other psychology-related jobs,” she said, adding that she’s in graduate school now, working on her doctor of nursing practice degree (DNP) to be a psychiatric nurse practitioner.

“I always thought that was a possibility, but I didn’t think this was the route I’d take,” she said. “For nurse practitioners, at least, the education track is different. So you’re a nurse first, so you get that compassionate care and bedside manner down first. And then you start learning the more advanced things.”

Once she has her DNP, she said she’d like to stay in the pediatric arena, although she’s hoping to gain a wide range of experience through her clinical rotations.

“Baystate in general is very supportive of education,” she added, noting the system’s tuition-reimbursement and loan-forgiveness programs, in addition to its affiliation with UMass Medical School’s Springfield campus, which is where she’s taking her graduate track.

“One of the reasons why I chose that school is because they have a focus on diversity and behavioral health,” she noted. “So I’ve been working hard, but I have also been lucky to find myself in places, and around people, that are supportive and inspirational, and I’ve been given a lot of opportunities to focus on the things that I want to do.”

As part of her graduate education, Ingraham-Shaw is hoping to focus on opioid and overdose education in her scholarly project. “It’s something I’m passionate about, and I’ve done a lot of my own learning. So I’m hoping to do some more research and actually implement some projects with that.”

For her work creating and cultivating a handful of truly impactful projects at Baystate already, but especially for the promise of what she and her colleagues have yet to come up with, Ingraham-Shaw is certainly an emerging leader in her field, and a Healthcare Hero. n

Practice Manager of Thoracic Surgery, Nursing Director of the Lung Screening Program, Mercy Medical Center

She Has a Proven Ability to Take the Bull by the Horns

It’s been seven years now, but Ashley LeBlanc clearly remembers the day Dr. Laki Rousou and Dr. Neal Chuang asked her to consider becoming the nurse navigator for their thoracic surgery practice at Mercy Medical Center.

She also clearly remembers her initial response to their invite: “absolutely not.”

She was working days in critical care at the hospital at the time, and liked both the work and the schedule: three days on, four days off, she told BusinessWest, adding that it takes a while for a new position like this to get approved and posted, for interviews to take place, and more — and the doctors used the following weeks to make additional entreaties, with reminders that she wouldn’t have to work any weekends or holidays.

But the answer was still ‘no’ until roughly six months after that initial invite, when she had one particularly challenging day on the floor with a very sick patient. Challenging enough that, when Rousou tried one more time that afternoon, ‘no’ became “I’ll update my résumé and hear you out.”

“He got me at a weak moment, and it was the best decision I ever made, because they have been amazing mentors, and they’ve opened my mind up to this whole other world,” she said, adding that her career underwent a profound and meaningful course change, one that led her to being named a Healthcare Hero for 2023 in the Emerging Leader category.

Indeed, during those seven years, LeBlanc has emerged as a true leader, both in that thoracic surgery practice, which she now manages, and in efforts to promote awareness and screening for lung cancer — one of the deadliest cancers, and one she can certainly relate to personally. Indeed, she has lost several family members to the disease, many of whom would have qualified for screening had it been available at the time of their diagnosis.

“He got me at a weak moment, and it was the best decision I ever made, because they have been amazing mentors, and they’ve opened my mind up to this whole other world.”

In many respects, and in many ways, she has become a fierce advocate for patients related to lung cancer screening, treatment, and research, and concentrates her efforts on ways to decrease the mortality rate of lung cancer and break down the stigma of that disease by educating the community, connecting them to resources, and, in many respects, guiding them on their journey as they fight lung cancer.

When the screening program was launched, those involved didn’t really know what to expect, LeBlanc said, adding that, in the beginning, maybe a handful of people were being screened each month. Now, that number exceeds 250 a month, and while only a small percentage of those who are screened have lung cancer, she said, each detected case is important because, while this cancer is deadly, early detection often leads to a better outcome.

This is turning out to be a big year for LeBlanc, at least when it comes to awards from BusinessWest. In the spring, she suitably impressed a panel of judges and became part of the 40 Under Forty Class of 2023. And in late October, she’ll accept the Healthcare Heroes award for Emerging Leader.

The plaques on her desk — or soon to be on it — speak to many qualities, but especially an ability to work with others to set, achieve, and, in many cases, exceed goals, not only with lung cancer screening, but other initiatives as well.

Dr. Laki Rousou never stopped trying to recruit Ashely LeBlanc to manage the thoracic-surgery practice at Mercy Medical Center, and he — and many others — are glad he didn’t.

Staff Photo

Rousou put LeBlanc’s many talents in their proper perspective.

“Before we even had the formal program, I would say something sort of off the cuff, like, ‘I wish we could do this’ … and the next week, I would have the answer, or it would be done,” he said. “Then it turned into ‘OK, let’s try and do this,’ and in the next week or two weeks, it would be done. And then it turned into a situation where she would have an idea and we would talk periodically, but she would take the bull by the horns and just do things that were best for thoracic surgery, but also the screening program.”

This ability to take the bull by the horns, and many other endearing and enduring qualities, explains why LeBlanc is a true Healthcare Hero.

The Big Screen

There’s a small whiteboard to the right of LeBlanc’s desk. Written at the top are the words ‘World Conquering Plans.’

This is an ambitious to-do list, or work-in-progress board, with lines referencing everything from a cancer screening program for firefighters to something called a Center for Healthy Lungs, which would be … well, just what it sounds like. “That’s a bit of a pipe dream,” she said. “We’re going to need our own building.”

While it might seem like a pipe dream, if it’s on LeBlanc’s list of things to get done … it will probably get done. That has been her MO since joining the thoracic surgery practice, and long before that, going back, for example, to the days when she worked the overnight shift as a unit extender at Mercy until 7, then drive to Springfield Technical Community College for nursing classes that began at 8.

“Sometimes, I would snooze in the car for 15 or 20 minutes,” she recalled, adding that she wasn’t getting much sleep at that time in her life. “You just do what you have to do to make it happen.”

Initially, she thought what she wanted to make happen was a career in law enforcement — her father was a police officer in Northampton — but her first stint as a unit extender at Mercy, while she was attending Holyoke Community College, convinced her she was more suited to healthcare.

But plans to enter that field were put on ice (sort of, and pun intended) when her fiancé, a Coast Guardsman, was stationed in Sitka, Alaska.

She spent three years there, taking in winters not as bad as most people would think, and summers not as warm as they are here, but still quite nice. And also working for the Department of Homeland Security as a federal security agent for National Transportation Safety Board at Sitka’s tiny airport.

“The evidence is staggering concerning the number of people who have a scan done, and they have an incidental finding, and there is no follow-up for that incidental finding.”

LeBlanc and her husband eventually returned to Western Mass. after a stint on the Cape, and she essentially picked up where she left off, working as a unit extender at Mercy.

“It was five years later, and it felt like I never left,” she said, adding that she soon enrolled in the Nursing program at STCC and, upon graduation, took a job on the Intermediate Care floor, which brings us back to the point where she kept saying ‘no’ and eventually said ‘yes’ to Rousou and Chuang (who is no longer with the practice).

Rousou told BusinessWest they recruited her heavily because they knew she would be perfect for the role they had carved out — and they were right.

Over the past seven years, LeBlanc has put a number of line items on the ‘World Conquering Plans’ list, and made most of them reality, especially a lung cancer screening program, which wasn’t even on her radar screen when she finally agreed to interview for the job.

Indeed, she was prepared to talk about patient education and how to improve it and make it more comprehensive when Rousou and Chuang changed things up and focused on a screening program.

Thinking Big

Once she got the job, she focused on both, with some dramatic and far-reaching results.

As for the screening program, she said such initiatives were new at the time because the Centers for Medicare Services had only recently approved insurance coverage for such screenings. At Mercy, with Rousou, Chuang, and, increasingly, LeBlanc charting a course, extensive research was undertaken with the goal of incorporating best practices from existing programs into Mercy’s initiative.

“We had no idea what our expectations should be or how it would be received in the community — it was a very new thing,” she recalled. “That first month in 2017, we did seven scans; then we did 29, and by the end of the year, it was over 50 scans a month. A year after we started, it was over 100.”

Now, that number is more than 250, she said, adding that such screenings are important because, while lung cancer is the deadliest of cancers, there are usually no visible signs of it — such as unexplained weight loss, coughing up blood, or pneumonia — until its later stages.

“When patients are diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer, the treatment is, by and large, palliative, not curative,” she explained, “which makes it extra important to try to diagnose these people with lung cancer at an earlier stage.”

In addition to her work coordinating the screening program, LeBlanc also handles work implied by her initial title — nurse navigator.

This is work to help the patient understand and prepare for the procedure they are facing, such as removal of a portion of their lung, and answer any questions they may have.

“When the surgeon leaves the room … that’s when a patient will take that deep breath and say, ‘I have so many questions,’” she told BusinessWest. “It can be overwhelming, and this gives me an opportunity to answer those questions, which can involve anything from the seriousness of the procedure to where to park or what to bring to the hospital with them.”

Meanwhile, she has taken a lead role in efforts to build a strong culture within the thoracic surgery and cancer screening programs, where 14 people now work, and make it an enjoyable workplace, where birthdays and National Popcorn Day are celebrated, and teamwork is fostered.

“I think it’s important to enjoy where you work, and when we’re happy, I think that carries over to patients, and they feel that,” she said. “At Easter, we have an Easter egg hunt, with grown, professional adults running around the office looking for Easter eggs. It seems silly, but it’s wonderful at the same time.”

Then, there’s that ‘World Conquering Plans’ board next to her desk. LeBlanc said she and the team at the practice have made considerable progress with many of the items on that list, including plans to expand the office into vacated space next door with an interventional pulmonary department and an ‘incidental nodule’ program.

The interventional pulmonary program is a relatively new specialty that focuses on diagnosis of lung disease, she said, adding that an interventional pulmonologist has been hired, facilities have been created, and patients have been scheduled starting early this month.

Progress is also being made on the incidental nodule program, which, as that name implies, is a safety-net initiative focused on following up on the small, incidental nodules on the lungs that show up on scans other than lung cancer screenings and are often overlooked.

“The evidence is staggering concerning the number of people who have a scan done, and they have an incidental finding, and there is no follow-up for that incidental finding,” she explained, adding that such findings often get buried or lost in reports. “When patients come to Dr. Rousou, they’ll often say, ‘I’ve had a scan every year for the last so many years; how come no one saw this until now?’”

Breathing Easier

As for the Center for Healthy Lungs … that is a very ambitious plan, she said, one that exists mainly in dreams right now.

But, as noted earlier, LeBlanc has become proficient in making dreams reality and in drawing lines through items on her whiteboard.

That’s what Rousou and Chuang saw when they recruited LeBlanc — and kept on recruiting her after she kept saying ‘no.’

They could see that she was an emerging leader — and a Healthcare Hero. n

Personal Trainer and Owner, Movement for All

She Inspires Others to Improve Their Mobility — and Quality of Life

One of Cindy Senk’s first experiences with yoga wasn’t a positive one.

Her back was very painful on the right side. “The yoga teacher came up in my face and said, ‘you can do better, you can do better’” — but not in an encouraging way, she recalled.

“It was almost hostile — this in-my-face attitude,” she went on. “I was really taken aback by that. I felt like, you don’t know me; you don’t know my health history; you don’t know what I’m feeling. I wanted to say, ‘get out of my face,’ but I didn’t — I just stepped back, and I never went back to that yoga studio.”

The experience drove her when she launched her own fitness and training practice, Movement for All, 20 years ago.

“I decided I would never be that teacher. I would never put someone in that particular place,” Senk told BusinessWest. “My philosophy as a teacher is to educate and empower my students, my clients, to make the choices that feel right because they feel it in their body. They know how they feel.”

That philosophy has led her not only to success with Movement for All, but 40 years of successes with specific populations, like people with arthritis, older individuals, and clients with cognitive challenges — because she understands that everyone, no matter their challenges, can thrive when they’re not treated in a cookie-cutter way.

Kelly Gilmore understands this. One of three clients who nominated Senk as a Healthcare Hero, Gilmore, a department chair at West Springfield High School, was hospitalized with a condition that diminished her mobility, stamina, and overall physical and mental state so severely that she couldn’t return to her teaching position.

“None of the numerous medical specialists that I continued to see regularly could offer a path toward improvement, beyond pain relief,” she wrote. “I set out to find a healthcare/fitness professional that was committed to helping me restore my health, strength, and mobility. Cindy offered exactly that. She met me where I was and created a personalized plan to move me to where I needed to be. She empowered me to take charge of my healing, unlocking the power inside of me, one step at a time.”

Starting a yoga regimen sitting in a chair, rather than on a mat on the floor, Gilmore began, within the next few months, to move freely, climb stairs, and go on walks. “Most importantly, I was in charge of my classroom again, offering my students the energy and vitality they deserve from their teacher.”

That’s real impact on clients with real problems. Multiplied over four decades, it’s a collective impact on the community, especially populations not always served well, and it certainly makes Senk deserving of being called a Healthcare Hero.

Brotherly Inspiration

Senk traces her passion for helping people to her childhood — in particular, her experiences with her younger brother, Bobby, who was born with cerebral palsy in 1955, long before the Americans with Disabilities Act codified many accessibility measures.

But Bobby had his family.

“My mother was a real advocate for him,” Senk recalled. “And we grew up in this environment in Forest Park where Bobby was one of the gang. We would accommodate him if he had trouble keeping up because of his crutches; we would just get him in a wagon and drag him around the neighborhood. He was always just part of the group. There was no, ‘well, Bobby can’t do that, so we can’t do it.’ It was never like that. It was always, ‘how can we creatively include him?’ And I think that’s really where this passion of mine comes from.”

Senk has had her own share of physical challenges as well; she was diagnosed with spinal issues at age 18 — issues that led to a lifetime of arthritis and have given her unique insight into people with similar problems, and led her into decades of advocacy in the broader arthritis community.

She’s never been free from arthritis; in fact, the day she spoke with BusinessWest at her home, Senk said she woke up with a lot of pain.

“My philosophy as a teacher is to educate and empower my students, my clients, to make the choices that feel right because they feel it in their body. They know how they feel.”

“It was just one of those days, you know?” she said. “So I started my gentle yoga I do every morning, I got in the shower, I was moving around my house, I had a class online that I teach, and then I had a client. And now I feel 1,000% better from when I woke up at 5:30 because I’ve been moving for six hours.

“It comes down to wanting to help people be functional, be fit, and have tools they can use to help themselves with whatever challenges they’re facing. And I think my passion for that came from a young age. Everything kind of flowed from all that: discovering how movement helps me and sharing that with others. Because I know how much movement helps me.”

Senk started her career with group exercise like step aerobics and regular low-impact aerobics, and later started practicing yoga to help her back — her main arthritic trouble spot. That was 35 years ago, and yoga has been an important part of her practice ever since.

Cindy Senk calls these women “the heart of my in-person classes on Tuesday nights.”

“I have my basic certification, but then I have specialties in yoga for arthritis, accessible yoga, subtle yoga, and I use all of those to put together whatever program I need for this particular client in this particular class. I feel lucky to have a lot of tools in my toolbox.”

It’s been gratifying, she said, to help clients discover those tools, especially those who didn’t think they could achieve pain relief and mobility.

“A lot of times, in the beginning, people that are in chronic pain are very tentative about movement because they think they’re going to hurt worse,” she said, adding that she draws on her experience as a volunteer and teacher trainer with the Arthritis Foundation — and her own experience with arthritis, of course — to help them understand the potential of yoga and other forms of exercise.

“It’s the idea of the pain cycle, where we think, ‘oh I can’t; it hurts,’ so we move less, and then we hurt more,” she explained. “The idea of movement breaks that pain cycle. You’re giving the power to the client through movement. It’s a journey that I’m on with them.”

It’s a good idea, Senk said, for people in pain to first see their primary-care doctor or a specialist to find out exactly what’s wrong and what their options are, whether that’s yoga, an aquatic program, a walking program, or another activity that can keep them mobile.

“She met me where I was and created a personalized plan to move me to where I needed to be. She empowered me to take charge of my healing, unlocking the power inside of me, one step at a time.”

“There are more than 60 million of us in this country who have arthritis — and that’s doctor-diagnosed, so a lot of people probably have arthritis and are not doctor-diagnosed. And it’s not just older people; it’s kids as well. It’s very pervasive, unfortunately. So you need to get the knowledge first, and then, if you want to move and exercise or whatever it may be, you need to find a professional who knows what they’re doing.”

Living Her Passion

Senk’s four-decade career as a fitness professional has brought her to commercial fitness settings, hospitals, senior-living communities, corporate environments, and the studio she runs out of her own home. She has also taught as an adjunct professor at Holyoke Community College, Springfield College, and Manchester Community College, in addition to 25 years of volunteerism with the Arthritis Foundation and her role chairing of the Western Massachusetts Walk to Cure Arthritis for the past three years.

That’s a lot of passion poured into what essentially boils down to helping people enjoy life again.

“The bottom line for me is to just encourage people to find things that are helping them stay functional, whether it’s a gym they love to go to or a more private type of setting like I offer here,” she said, noting that her home studio also includes outdoor activities and virtual classes.

“I think it’s important for people to find where they fit, where they’re comfortable. And if they go to a gym or they go to a yoga studio and it’s not their fit, just keep looking. Find your people. Find the people that really speak to you and that will support you and not judge you and not put you down because maybe you can’t bend as much.”