Professional Development — by Design

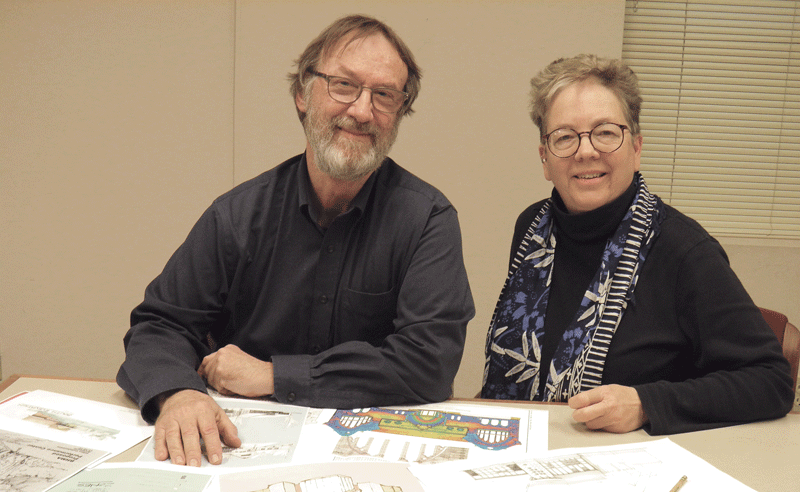

Clockwise from top: CFO Tina Gloster and Principals Kevin Riordon, Lee Morrissette, and Jason Newman (Photo by Paul Schnaittacher)

To explain what it means to be named an Emerging Professional Friendly Firm, Jason Newman offered some background on what it’s like to be an aspiring architect.

‘Aspiring,’ because simply earning a degree and going to work at an architecture firm doesn’t make one an architect; other requirements are experience — a certain number of hours worked in the field — and a series of examinations.

“Part of the experience piece is the hours worked in this office, and those hours are not just a lump-sum number of hours worked — it’s a number of hours worked in specific categories of the profession, like drawings, construction administration, and practice management,” said Newman, a principal at Dietz & Company Architects in Springfield.

“One of the things we pay attention to, very thoughtfully for every employee, is that, if you’ve got all your drawing hours satisfied, we’re not going to make you do drawing for another two years,” he went on. “That’s not going to move you forward to your license. So you won’t come to the end of the road here at Dietz and feel, ‘I’m just getting drawing. I have to go somewhere else where I can get construction-management experience.’

“If you’ve got all your drawing hours satisfied, we’re not going to make you do drawing for another two years. That’s not going to move you forward to your license.”

“This is not Boston, where 100 qualified architect candidates are at our door. We have to take care of the people here because we want them to stay,” he went on. “We want to make sure that they feel growth opportunities are here.”

That’s precisely the philosophy behind the Emerging Professional Friendly Firm program overseen by the New England components of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). A handful of firms in each New England state are so recognized each year — Dietz among them for several years running — for promoting the advancement of young team members through professional development and personal growth opportunities.

“A few years back, AIA New England came out with programs to encourage companies to adopt policies and procedures and training and internal education programs that would further develop the younger generation of architects fresh out of school, to take them in and help them grow professionally toward architecture licensure, which is what everyone refers to as the ‘stamp.’ That’s when you officially call yourself an architect,” Newman explained.

“This is a program to encourage firms to get away from the old methods of pigeonholing, where, in many cases, your first experience on an architecture job was drawing bathrooms for three years, being tucked into one thing because you’re brand new,” he went on. “The goal of this program was to incentivize firms to be more supportive, to promote emerging professional development.”

Lee Morrissette, another principal, spent more than a decade in Boston before coming to Dietz, and said he has always appreciated its emphasis on mentorship, continuing education, and lifelong investigation of the profession. “It’s a much more transparent firm, in the way the business goes on, than anywhere I’ve been.”

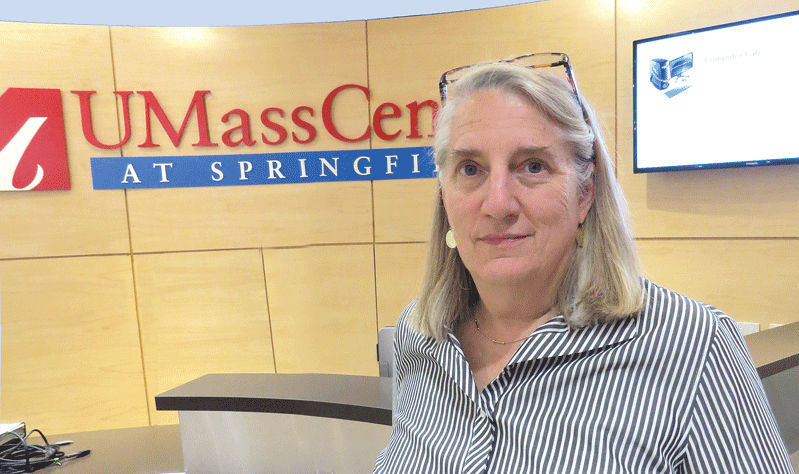

Jason Newman

“A lot of the junior staff see when we get praise for our designs — or criticized for our designs. It gives them a fuller perspective on what’s happening beyond the drawings.”

It certainly made an impression on Newman, who came to Dietz as a student intern 13 years ago and “never found a reason to leave,” as he put it. “So I’m an example of someone to wants to stay with this firm because they feel this is a good, long-term place for them.”

Drawing Up a Strategy

According to AIA New England, the Emerging Professional Friendly Firm program “has an ability to attract and retain employees by sending a message to current employees, future employees, and other regional firms that the firm has evaluated their policies from an emerging professional lens, the firm recognizes emerging professionals at their firm, and the firm values emerging professionals’ development to sustain the future growth of their practice.”

That resonates with Newman, who noted that the aim is for young professionals to think, “that’s a great place for me to be. That’s a great place for me to grow. I know, when I go to other firms, my development will be of value not only to me, but to the company and the people I’m working with.”

To earn that designation year after year has involved a series of proactive steps, Morrissette said, including that emphasis on diverse experiences that move staff toward licensure more quickly.

“Many larger firms get a bad reputation for being the kind of firm where you get stuck in a position, doing that function for a long time, falling between the cracks,” he noted. “We call ourselves a mid-sized firm — at 25 people, we’re the largest in Western Mass., but still a mid-sized firm for the country — so we get a lot of face time with the staff. It’s hard for someone to fall through the cracks here.”

In addition, Newman said, “we make sure entry-level people are getting the whole experience. We include the whole team in project meetings. I’ve been in the industry 13 years, and back then, the architect and the project manager went to the meeting, and they came back and told you what happened.”

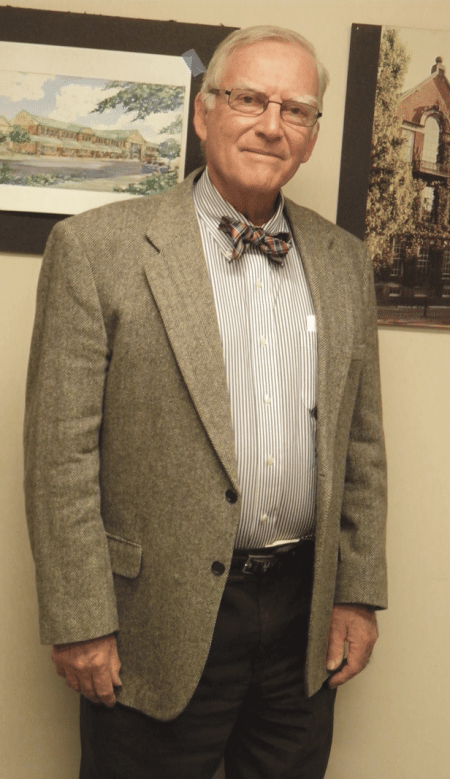

Lee Morrissette

“Over the past two years, we’ve spent more time doing creative designs. That’s what makes us happy as professionals — being able to stretch our creative muscles and push ourselves.”

But the rise of remote meetings made it more common to include everyone, and now it’s simply firm policy at Dietz.

“A lot of the junior staff see when we get praise for our designs — or criticized for our designs. It gives them a fuller perspective on what’s happening beyond the drawings,” Newman explained. “Twenty to 30% of what we do as architects is management of expectations, helping people pull their own creativity into the designs, helping them express ideas that they don’t know quite how to express. Well, this gives the junior staff exposure to that earlier than what they have been given traditionally.”

All staff members are also given a stipend each year, called an educational allowance, which can be used for anything they feel will better their professional development.

“Architecture is a mixture of art and science, and we want to create buildings that are beautiful and people want to look at, but also stand up and are good, strong structures,” Newman noted. “So we allow a very broad interpretation of what is an activity or class or training someone might feel would better their professional growth. It might be as simple as a painting class, targeting the artistic side, or a business of architecture class, or project management class, or they might want to buy books because they’re studying for an exam. People use it in very creative and interesting ways.”

Morrissette and Newman also value the culture of mentorship they’ve seen — and helped cultivate — at Dietz & Company.

“We both love teaching. We both participated in university reviews of student works in a volunteer way,” Morrissette said, adding that he has taught at Wentworth Institute of Technology in Boston as adjunct faculty. “I loved being involved. But we’ve found, with this focus on teaching and mentoring in the office, we can do that teaching here. For me, it satisfies the reward I get from teaching and mentoring professional staff, and I get to do it as part of my job.”

Something to Build On

That job has expanded since Newman, Morrissette, Principal Kevin Riordon, and Chief Financial Officer Tina Gloster began easing into leadership roles last year as part of the firm’s transition from a single owner — President and Trustee Kerry Dietz — to one with an employee stock-ownership plan, or ESOP. Meanwhile, the firm has continued to expand its footprint, including more work outside the 413.

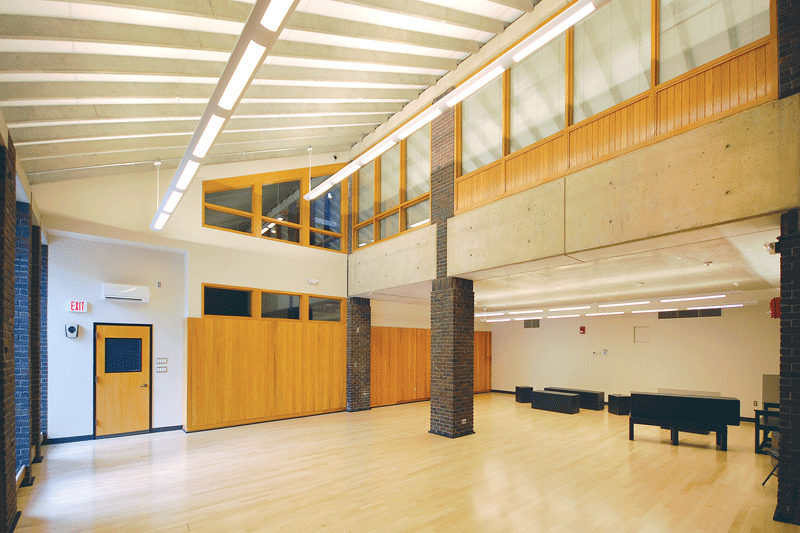

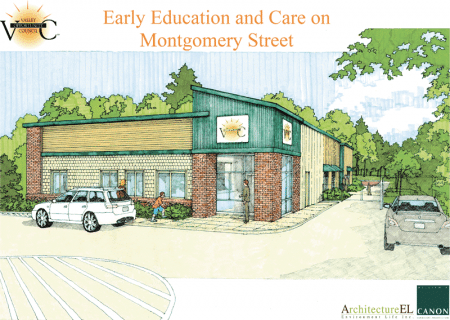

“It’s been a really great year. We’ve had a tremendous amount of work,” Newman said, adding that, while not every project is exciting from a creative perspective, he’s gratified to work on anything that benefits a community or a client. But some of this past year’s work has, indeed, been on the “cool” side. “We’ve shown we can get in with the Boston guys and compete. It’s really encouraging. It shows our model is working and we’re getting better and better every day.”

Morrissette agreed. “As an architecture firm, we’re always looking for more work. You want to do everything; the company wants to pay the bills. But over the past two years, we’ve spent more time doing creative designs. That’s what makes us happy as professionals — being able to stretch our creative muscles and push ourselves.

“You know, we feel creative success at the end of a project that no one knows about for a year or two until it’s built. Then they say, ‘that’s a great project.’ We have projects we’re proud of, and we can’t wait for the public to see them.”

As one local architect noted, we’re far enough away from the last recession to start worrying about the next one — and recessions tend to hit this sector particularly hard. Still, despite mixed signals in the long-term economic picture nationally, work remains steady locally, with municipalities, colleges, and businesses of all kinds continuing to invest in capital projects. Even if storm clouds do appear down the road, the 2019 outlook in architecture seems bright.

As one local architect noted, we’re far enough away from the last recession to start worrying about the next one — and recessions tend to hit this sector particularly hard. Still, despite mixed signals in the long-term economic picture nationally, work remains steady locally, with municipalities, colleges, and businesses of all kinds continuing to invest in capital projects. Even if storm clouds do appear down the road, the 2019 outlook in architecture seems bright.

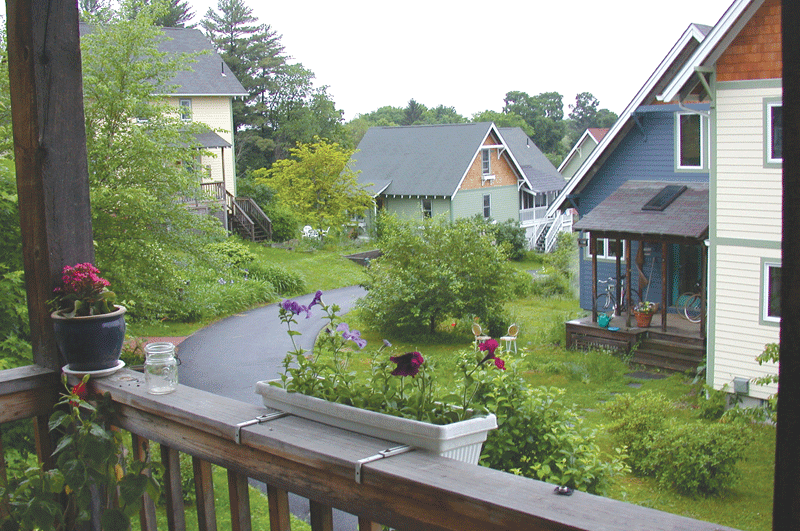

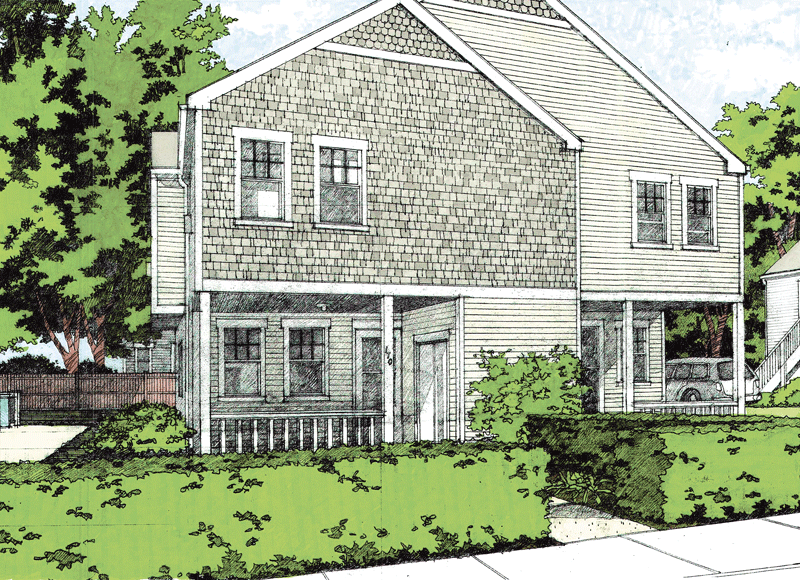

The ideas home buyers — and those looking to renovate — bring to the table can morph over time, and a few trends, including an emphasis on open floor plans and sustainable living, not to mention natural surfaces and unobtrusive, smart technology, have come to dominate today’s residential-design world. And when the end result matches the initial vision, well, that’s when a house truly becomes a home.

The ideas home buyers — and those looking to renovate — bring to the table can morph over time, and a few trends, including an emphasis on open floor plans and sustainable living, not to mention natural surfaces and unobtrusive, smart technology, have come to dominate today’s residential-design world. And when the end result matches the initial vision, well, that’s when a house truly becomes a home.