Paying Dividends

JA Provides Critical Lessons in Business, Life

Jennifer Connolly stands beside the portrait of JA co-founder Horace Moses at the agency’s offices in Tower Square.

Jennifer Connolly likes to say Junior Achievement works hard to present young people — and, in this case, that means kindergartners to high-school seniors — with eye-opening and quite necessary doses of reality.

And one of the more intriguing — and anecdote-inspiring — examples is an exercise involving second-graders — specifically, an individual wearing a nametag that reads simply, ‘Tax Collector.’

The best story I ever heard from one of our volunteers was about how he announced to the class that it was time to take the taxes, and this one boy dove under his desk and said, ‘no, no, my daddy says taxes are bad … I don’t want to pay taxes!”

You guessed it. This is a direct lesson in how the amount of money one earns certainly isn’t the amount taken home on payday. In this case, the tax collector, often one of the students, literally takes away two of the five dollars a student has ‘earned’ for work they’ve undertaken.

The exercise has yielded some keepsake photos for the archives, and colorful stories that Connolly, president of Junior Achievement of Western Massachusetts, has related countless times.

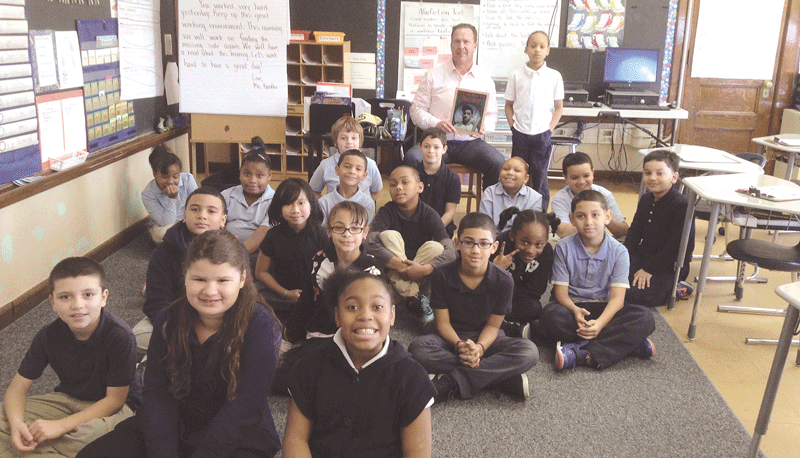

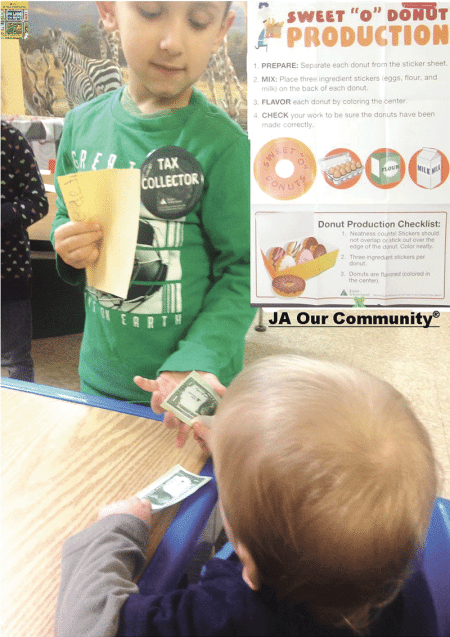

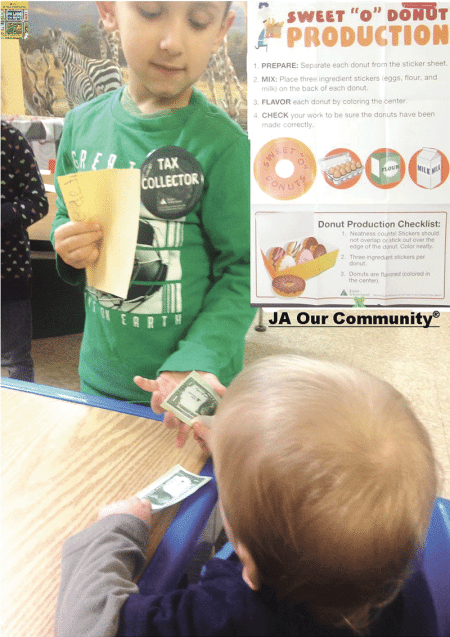

The ‘tax collector’ makes his rounds at a local school. The exercise provides important lessons and has yielded some colorful anecdotes.

“The best story I ever heard from one of our volunteers was about how he announced to the class that it was time to take the taxes,” she recalled, “and this one boy dove under his desk and said, ‘no, no, my daddy says taxes are bad … I don’t want to pay taxes!’

“And the students … they don’t want to be the tax collector,” she went on. “We sometimes have to get one of our volunteers to do it. The kids cry — they don’t want to take money away from people; they say, ‘I can’t do this.’ It’s adorable.”

That’s not a word that applies to all the lessons, obviously, including one that Connolly imparted on a local high-school student herself.

“One girl couldn’t decide between being an early-childhood educator or a doctor,” she explained. “She looked at the income for an early-childhood worker and said, ‘that’s terrible,’ and I said, ‘unfortunately, yes.’

“So she said, ‘I’ll go into allied health, become a doctor, and make a lot of money,’” Connolly went on. “That’s when I told her about one of my daughter’s friends who became a dentist; she owes $250,000 in student loans, is back home living with her parents, and drives the same minivan she had when she was in college. I told this student there are no easy choices, and you have to weigh the impact, and she replied, ‘you’ve given me so much information, my head is going to explode.’”

Whether adorable or biting in their nature, the lessons provided by JA are, in a word, necessary, said Connolly and others we spoke with. That’s because they help prepare young individuals for the world beyond the classroom, where wrong decisions about finances can have disastrous consequences, and also where hands-on experience with the world of business can pay huge dividends and perhaps even inspire future entrepreneurs and business managers.

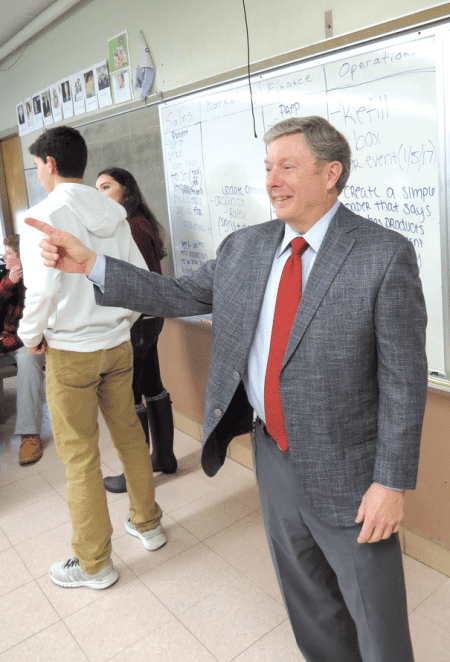

“It’s rewarding to watch the students and see the lightbulbs go on,” said Al Kasper, president and chief operating officer of Savage Arms in Westfield, who has been a long-time JA volunteer and board member.

At present, he mentors two entrepreneurship classes, or “company programs,” at East Longmeadow High School taught by Dawn Quercia, who has been doing this for nearly 20 years now, and is such a believer in the program that she fronts the startup money needed for her classes to place orders for the products they are to sell.

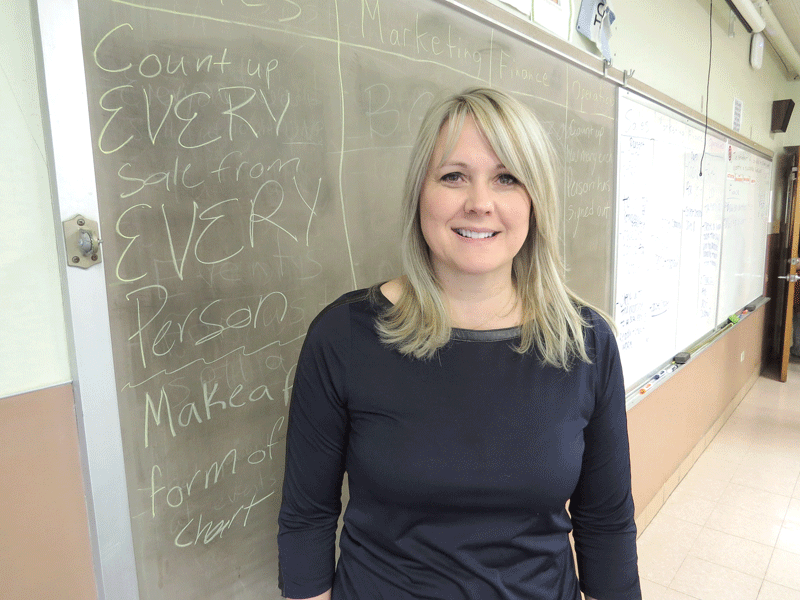

Dawn Quercia, who fronts the money for her business students’ ventures, says the JA program provides hands-on lessons one can’t get from a textbook.

“It’s a little risky … I’m not a wealthy person, but I believe in the kids,” she said, adding that the most she’s ever lost is $200, and all she ever gets back is her investment — there’s no interest.

The dividend, she went on, is watching students learn by doing and gain maturity and life lessons while doing so.

“I could teach this out of a book, and that’s what I did when I first started here,” she went on. “And I didn’t feel the kids were learning as much as they could, and I said, ‘why don’t we just start a business?’”

Young people have been doing just that since 1919, when Horace Moses, president of Strathmore Paper Co., collaborated with other industry titans to bring the business world into the classroom by having students run their own venture.

And it continues today with a wide range of programs involving the full spectrum of young students — from those learning their colors to those trying to decide which college to attend.

JA is coming up on its centennial celebration, and since it was essentially born in Western Mass. (although now headquartered in Colorado Springs, Colo.), Connolly is hoping that Springfield, and perhaps the Big E — where the so-called Junior Achievement Building, built in 1925 and funded by Moses, still stands — can be the gathering spot for birthday celebrations.

But while she’s starting to think about a party, she’s more focused on providing more of those hard, yet vital lessons described earlier. And that’s why this organization was named a Difference Maker for 2017, and is clearly worthy of that honor.

Thinking Outside the Box

They’re called ‘memory boxes.’

That’s the name a small group of students from Roger L. Putnam Vocational Technical Academy in Springfield assigned to a product they conceived, assembled themselves, and took to the marketplace just over a year ago.

As the name suggests, these are decorated wooden boxes, complete with several compartments designed to store jewelry or … whatever. They were hand-painted, with stenciling and paper flowers glued on the top, and priced to sell for $15, with were being the operative word. That’s because, well, they just didn’t sell, and are now more collectors’ items than anything else.

But it wasn’t for lack of trying.

“They did everything to sell them — they kept getting knocked down, and they kept getting back up,” said Connolly, referring to the students involved in this exercise, which she supervised as part of the JAYE (Junior Achievement Young Entrepreneurs) program. “They tried craft fairs, flea markets, they tried online, they sold from a table at Tower Square … the boxes just didn’t sell.

“The girls just wouldn’t take ‘no’ for an answer,” she went on, adding quickly, though, that they heard ‘no’ more than enough times to convince them it was time to develop a new product. “They learned to take rejection very well.”

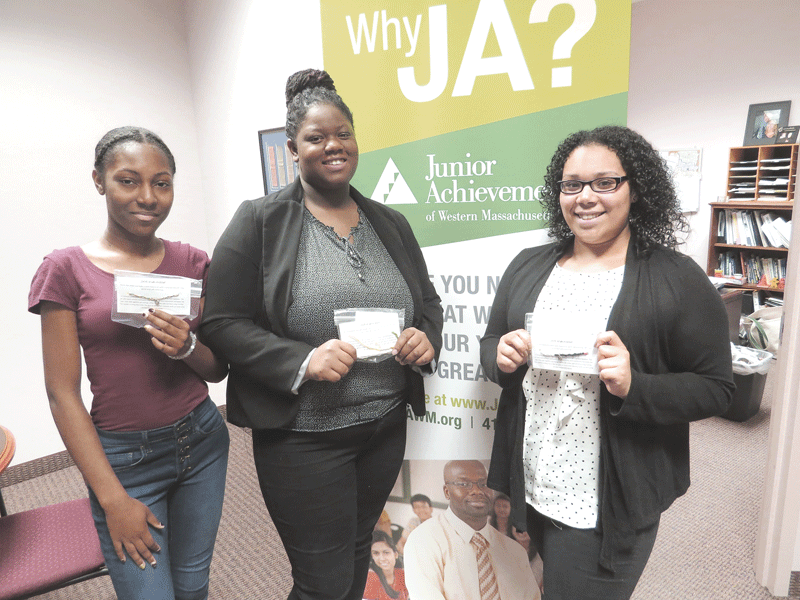

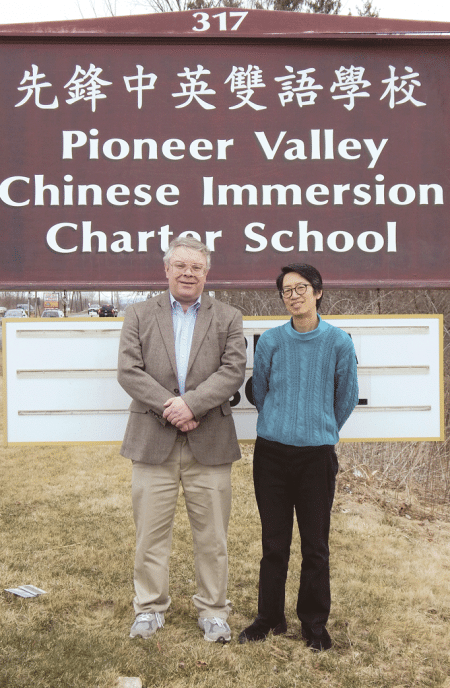

From left, Sabrina Roberts, Dajah Gordon, and Johnalie Gomez have learned some critical lessons selling ankle anklets — and not selling memory boxes.

And that, as it turned out, was only one of many lessons imparted upon them during that exercise, as was made clear by these comments from Dajah Gordon, a team member and JAYE veteran who has been part of far more successful ventures, including the team that went to the program’s national finals, staged in Washington, D.C., two years ago with a company that sold charm bracelets.

“Whenever we fail, like we did with the boxes, we have to step back, look at the company, and say, ‘where are we lacking?’” she said of the six-month odyssey with that ill-fated product, which all the participants can look back on now and laugh. “For us, with the boxes, something we didn’t focus on much was our target market; we were trying to sell to everybody, but we needed a specific target group or audience.

“Later, we got that part down,” she went on, adding that the identified audience — young people like themselves — has become far more receptive to the team’s new product, the so-called ‘wish anklet.’ (The wearer is to make a wish upon tying it around her ankle; if she keeps it on until it naturally falls off, the secret wish will come true.)

While there is no documented or even anecdotal evidence that the product performs as advertised, the anklets, introduced just a few months ago, have been selling well, and the three young women involved are certainly optimistic about fast-approaching Valentine’s Day, and are hard at work replenishing depleted inventory.

These collective exploits are typical of the JAYE initiative, an after-school version of the JA Company Program, which is the very bedrock on which the Junior Achievement concept was built in the months after World War I ended and when the nation was returning to what amounted to a peacetime economy.

Horace Moses; Theodore Vail, president of American Telephone & Telegraph; and Massachusetts Sen. Murray Crane got together behind the notion that, as the nation shifted from a largely agrarian economy to an industrial-based system, young people would need an education in how to run a business, said Connolly. A decidedly hands-on education.

Four and perhaps five generations of young people have formed enterprises and brought products to market through what is still known as the JA Company Program, as evidenced by the front lobby of the JA office on the mezzanine level in Tower Square, which has a number of artifacts, if you will, on display.

There are no memory boxes, but on one table, for example, is what would now be considered a very rudimentary, wooden paper-towel-roll holder, as well as a small rack for key chains, both products conceived by high-school classes in the ’70s, said Connolly.

On another table by the front window, near a large, imposing painting of Horace Moses (a prized possession for this JA chapter), is a wooden lamp, a product produced in the late ’70s through a JA Company Program called Bright Ideas, sponsored by what was then called Western Mass. Electric Co. (now Eversource). Connolly noted that lamps of various kinds were a staple of early JA ‘company’ classes, which started as after-school exercises and eventually moved into the classroom in the late ’50s.

Today, there are in-class and after-school programs that are providing students with tremendous opportunities to not only learn how a business is run, but operate one themselves, experiencing just about everything the so-called real world can throw at them.

Learning Opportunites

That would definitely be the case with another after-school JAYE program, said Connolly, this one called the Thunderpucks.

A collaborative effort involving students at Putnam, Chicopee High School, and Pope Francis High School, this bold initiative essentially makes a team of students part of the staff of the Springfield Thunderbirds, the new AHL franchise that started play last fall amid considerable fanfare and promise.

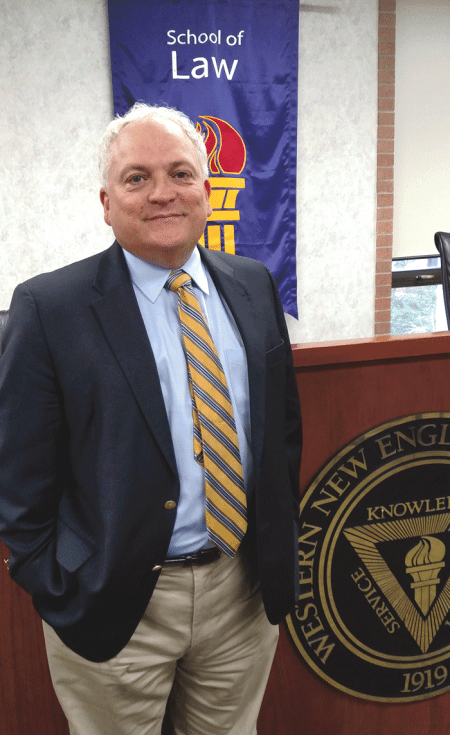

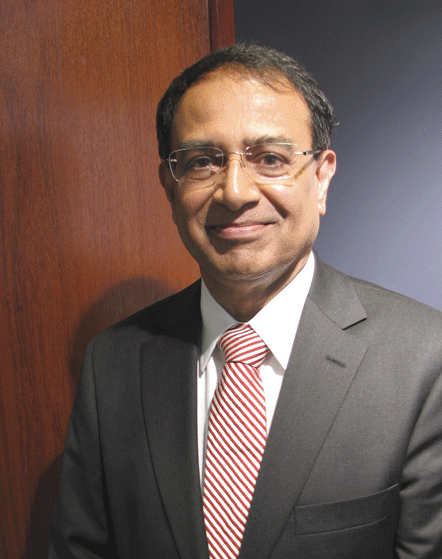

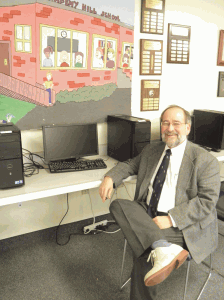

Al Kasper says he enjoys seeing the “lightbulbs go on” as he mentors students involved in JA programs at East Longmeadow High.

This team has been assigned the March 3 tilt against the Lehigh Valley Phantoms and will coordinate many aspects of it, from the band that plays the National Anthem to the T-shirt toss, to some ticket sales, said Connolly.

“They’re going to be reaching out to businesses and groups and trying to sell them ticket packages,” she explained. “They’re going to be handling almost all aspects of the game; it’s an incredible learning experience.”

Those last two words, and even the one before them, would apply to most all JA initiatives, she went on, adding, again, that they start with children at a very young age.

With that, she took BusinessWest through the portfolio of programs, if you will — one that involved some 11,500 students across the region during the 2015-16 school year — starting in kindergarten.

At that age, the focus is on very basic financial literacy, such as understanding currency and the concept of a savings account. By first grade, students are acquainted with jobs, businesses, the assembly line (they create one to make paper donuts), and the term ‘income,’ and how families must live within one. This is when they are told about the difference between a ‘want’ and a ‘need.’

Moving along, in second grade, the tax collector makes his arrival — money is taken from those working to make donuts and given to those working for the government, so students can see where their tax dollars go, among other lessons. In third grade, students learn how a city operates and are introduced to concepts such as zoning, planning, and the basics of running a business.

And on it goes, said Connolly, adding that, by sixth grade, students are learning about cultural differences and why, for example, they can’t sell hamburgers in India. By middle school, there are more in-depth lessons in personal finances, budgeting, branding, and careers — and how to start one — as part of the broad Economics for Success program.

By high school, the learning-by-doing concept continues with everything from actual companies to stock-market challenges; from job shadowing to lean-manufacturing concepts. And while students learn, they also teach, with high-school students mentoring those in elementary school, and college students returning to coach those in high school.

The work of providing all these lessons falls to a virtual army of volunteers, said Connolly, adding that the Western Mass. chapter deployed more than 400 of them last year. They visited 522 classrooms and donated more than 73,000 hours to the area’s communities.

“JA is taking what students are learning in school, the math, the communications, the writing, all of that, and giving it a real-life reason,” she explained, summing up all that programming and its relative importance to the students and the region as a whole. “You need math because … you have to figure out your finances, or you might run a business. You need to understand social studies and geography because we’re an integrated world — where do the products come from?

“And the activities we have in JA are really hands-on, so we really promote critical thinking, analyzing, and problem solving,” she went on. “These are the 21st-century skills that students will really need.”

Returning to that episode involving the high-school girl trying to decide between early-childhood education and the medical field, and the choices involved with each path, Connolly said it reflects many of the lessons and experiences that JA provides.

“We don’t want to show them that everything’s easy — it’s not easy, no matter what you pick,” she explained. “We’re trying to make them think and make intelligent decisions.”

And this is certainly true when it comes to the JA Company Program, as we’ll see.

Course of Action

“Good cop … bad cop.”

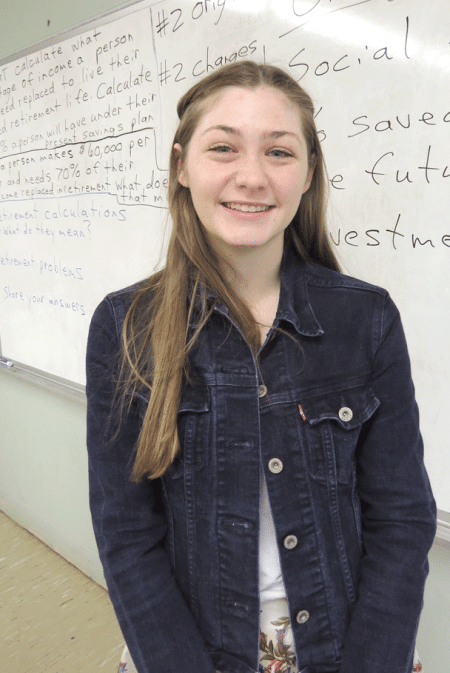

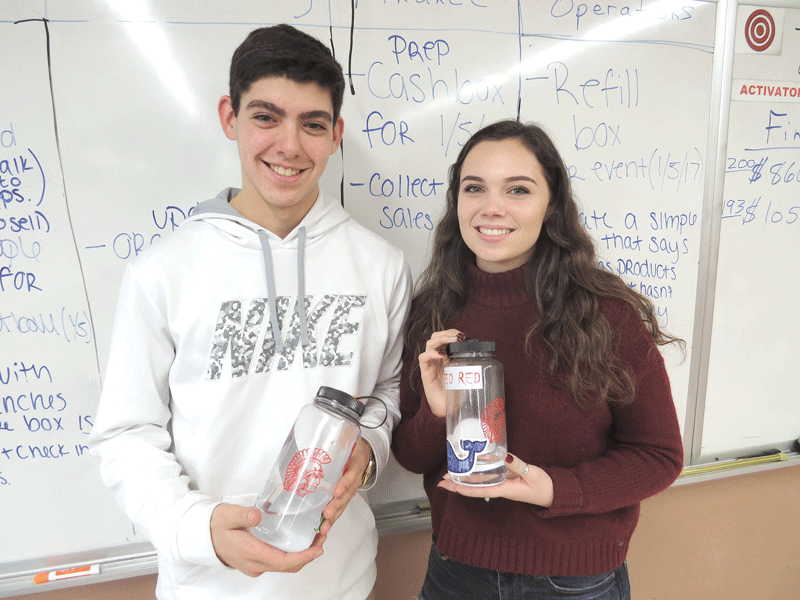

That’s how Katie Roeder, a junior at East Longmeadow High School, chose to describe how she and Seth Bracci, co-presidents of a company now selling sweatshirts, work together at their JA venture.

And she’s the bad cop, a role she thinks she’s suited for, and that she enjoys.

Katie Roeder says she enjoys her ‘bad cop’ role as co-president of a company at East Longmeadow High School selling sweatshirts.

“I’m the one who lays out the schedule, and I go around to different groups and check on them, and if they’re not where they need to do be, I ask them to do those things as soon as possible,” she explained. “And Seth … he comes in after that and says, ‘c’mon, guys, let’s do it,’ evening out the seriousness with a bit of fun.”

It all seems to be working, she went on, adding that this business doesn’t have a name, really; it’s merely identified by the class title and time slot: Entrepreneurship H Block (12:20-1:01 p.m.). It is one of two JA classes at the school, with the other selling water bottles, as we’ll see shortly.

The H Block class spent a good amount of time deciding on a product, Roeder told BusinessWest, adding that, while young people can buy sweatshirts in countless places, online and in the store, they can’t find one with the distinctive Spartan logo, or mascot, that has identified ELHS since it opened in 1960 — unless they’re on a sports team.

The class then spent even more time — too much, by some accounts — coming up with a design (gray sweatshirt with a red logo, covering both of the school’s colors), she went on, adding that Quercia insisted on making this a democratic exercise, with input from all those involved, to achieve as much buy-in as possible. Then it spent still more time conducting what would be considered market research on who might purchase the product before placing a large order with the manufacturer.

This was a fruitful exercise, Roeder noted, because it informed company officers that those most likely to buy were underclassmen and students at nearby Birchland Park Middle School who would soon become ninth-graders. Thus, the order was for large numbers of smalls and mediums, and only a handful of XLs and XXLs, presumably to be sold to alums at the Thanksgiving Day football game (and there were a few such transactions).

Such hands-on lessons in how businesses run, or should run, are what JA’s entrepreneurship program is all about, said those we spoke with, adding that the year-long exercise is an intriguing departure from learning via a textbook, such as in AP Calculus, which is where Roeder was supposed to be at that moment, only she got a pass so she could talk with BusinessWest.

“It’s great because it’s different from the day-to-day classroom things we do,” she noted. “We handle real money; this is a real business with real stakes. It doesn’t feel like a class at all. We’re learning, but it doesn’t feel like we are. All that knowledge still goes into our mind, and we keep it there.”

Bracci agreed. “It’s interesting to see the inner workings and just how hard it is to create your own business,” he explained, “and how there are many different obstacles you can run into as someone trying to get a product out there.”

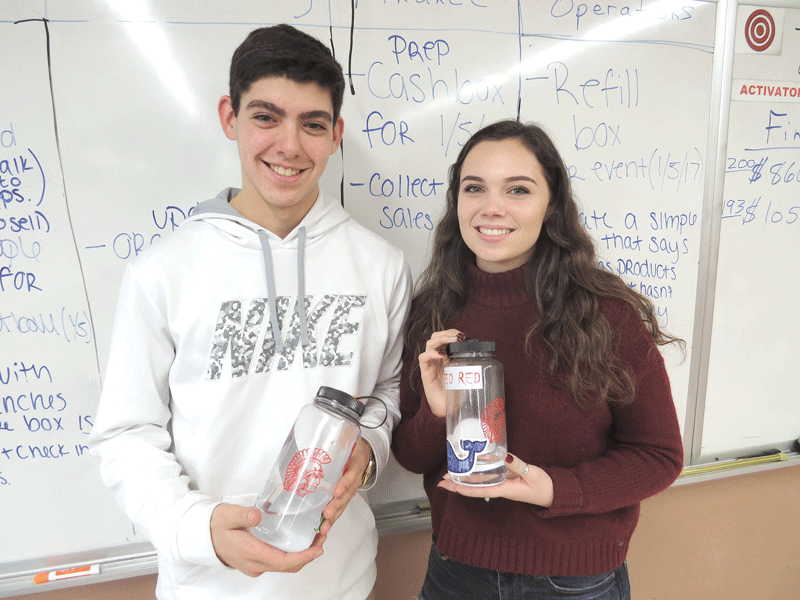

Meanwhile, at the water-bottle-selling company gathered next door, in room 111, the discussion focused on sales to date — and how to sell the 30 or so units still in inventory.

Co-president Bridget Arnesen, while occasionally drinking from one of the Spartan-logo-adorned bottles, exhorted her classmates to not rest on their laurels — bottle sales did well in the run-up to the holidays — and keep selling when and where they could, such as at the big basketball game slated for that night against league powerhouse Central.

This was where Kasper stepped in to evoke the ‘80-20 rule,’ which, he said, predicts how roughly 80% of a company’s products will be sold by 20% of its representatives.

A quick look at a tote board of sorts that detailed how many units each class member had sold, revealed that the 80-20 rule certainly held up in this case, with some class members clearly motivated by the $5.67 in commission they make for each bottle sold (one enterprising young woman logged 40 transactions), and others … not so much.

But the walking-around money is just one of the things students can take home from these classes, said Quercia, adding that the doses of reality can help in a number of ways, especially for those who have intentions of getting into business.

And Roeder already has such plans in the formative stage. She’s not sure where she’ll attend college — she says she’ll start kicking some tires next year — but does know that she intends on majoring in pediatric dentistry and probably owning her own practice.

“Business will help with my future career because I want to run a pediatric dentistry,” she explained. “I hope all the things I’ve learned stay in my head, because I’m going to need them.”

Life Lessons

Such comments help explain why those at BusinessWest chose Junior Achievement of Western Massachusetts as a Difference maker for 2017 and, more importantly, why the organization continues to broaden its mission and find new ways to impart hard lessons.

Indeed, it is comments of various types and from a host of constituencies that drive home the point that JA’s programs are more important now than perhaps ever before.

We could start almost anywhere, but maybe the best place is with Robbin Lussier, a business teacher at Chicopee High School and another educator who has a long history with JA.

It has included a number of initiatives, including a career-preparation program that has grown to include 120 students, who receive tips on résumés and how to search for a job, and actually take part in mock interviews with area business owners and managers.

Bridget Arnesen and Nathan Santos, co-presidents of the company at East Longmeadow High School selling water bottles, say their class provides real-life lessons in running an enterprise.

The lessons eventually turned into life experiences, she said, adding that many students actually earned jobs with area companies, prompting employers to come back year after year as they searched for qualified help.

Other involvement with JA has included programs in budgeting, personal finance, and the stock-market challenge, she went on, adding that they provided what she called a “heightened sense of reality” that a classroom teacher could not provide.

“It’s a whole new dimension — students are walking away with memorable lessons learned,” Lussier said, adding that some of the more intriguing things she hears are from those who are not taking part in these programs, but wish they could, or wish they had.

“I teach a personal-finance class this year,” she said, “and if I had a nickel for every time a teacher, administrator, or parent at open-house night said, ‘I wish I could take this class’ or ‘I wish they had this when I was in school,’ I could retire.”

Connolly agreed, and cited a 50-question quiz on debit and credit cards given recently to middle-school students at Springfield’s Duggan Academy as an example.

“At the end, after the volunteer had gone through all the questions, one girl turned to another and said, ‘this has been the best day … I learned so much today,’” she recalled. “And another said, ‘can I take this home so I can show my parent? Can I take this home so I can show my grandmother? I want to save this so when I go to college I can make the right decisions.’

“That’s what you live for, students who have that reaction,” she said, adding that she sees it quite often, which is encouraging.

Also encouraging is seeing students learn by doing, even if it’s difficult to watch at times, said Quercia, who was happy to report that both classes, first those selling water bottles and then those peddling sweatshirts, paid back the seed money she invested.

“They handle everything, I act as their consultant, and Al [Kasper] explains how everything they’re learning is like the real world,” she told BusinessWest. “Together, the students face challenges and confront problems and get creative in finding solutions together.”

Kasper, who has been involved with JA in various capacities since the early ’80s and at ELHS for 15 years now, concurred.

“This isn’t MCAS, ‘memorize-this-stuff’ learning,” he said of the company program. “It’s real-life stuff that students get excited about, and because of that, we’ve really grown this program.

“They’re excited to come to class,” he went on. “It’s something new, it’s reinforcing what they’re learning, and it’s fun. They’re still learning, but they’re having fun doing it, so the retention is great, and their confidence goes up.”

It’s All About the Bottom Line

When asked what she had learned about business through her involvement with JAYE, Johnalie Gomez, another member of the team from Putnam now selling wish anklets, thought for a moment before responding.

“It’s not … easy,” she said softly, deploying three little words, in reference to both business and life itself, that say so much that those around her immediately started shaking their heads — not in disagreement, but rather in solid affirmation, as if to say, ‘no, it’s not.’

Everyone who has ever been in business would no doubt do the same. And that’s because they probably have at least one ‘memory box’ or something approximating it somewhere on their résumé — a seemingly good idea that just didn’t work. With each one, there are hard lessons that bring pain, maturity, and, hopefully (someday), laughs.

Delivering such vital lessons when someone is in the classroom — or the conference room in the suite at Tower Square — so that they may resonate later and throughout life is why Junior Achievement was formed, why it continues to thrive, why it is even more relevant now than it was 98 years ago, and why the organization is a Difference Maker.

Just ask the ‘tax collector,’ or, more specifically, those young students who don’t want to be him.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]

Already, many have come to take in the Kern Center, he explained, adding that he is one of many who will give tours to those representing institutions such as Yale Divinity School, which is contemplating a village of buildings with similar credentials.

Already, many have come to take in the Kern Center, he explained, adding that he is one of many who will give tours to those representing institutions such as Yale Divinity School, which is contemplating a village of buildings with similar credentials.